An unsolved missing persons case from 1983 has been reopened by Kittery Police, due in part to the interest of a local detective who is breathing new life into the investigation of a man’s disappearance that has received little to no attention in nearly 40 years.

“I just think there’s more information out there that we’re just not touching, that we’re not privy to,” Kittery Police Det. Brian Cummer said.

The story of Reeves K. Johnson III, a local man, who was 31 when he went missing in February 1983, also piqued the interest of Kristin Seavey, the Newport-based host of “Murder, She Told,” a Maine-centered true-crime podcast. She aired an episode dedicated to the case last month, hoping the attention will lead to new information.

“I think that the best chance this case has is to have the most information out there to help it,” Seavey said.

Cummer said he first discovered the case more than five years ago. He was a patrol officer at the time, often working the overnight shift, and spent any spare time looking through old case files. He stumbled across the Johnson case, noting it was still unsolved, and that the last time anyone even touched it was in 2009.

“Basically nobody here knew anything about it,” he said.

Even when he became detective three years ago, Cummer said he had been too busy at the time to pursue it, but he literally kept it on the corner of his desk until October of this year, when he finally found time to ask permission to work on it.

Kittery Police Chief Robert Richter agreed.

The last time police can reliably confirm anyone seeing Johnson alive was on Thursday, Feb. 3, 1983, at his job as a welder at Donnelly Manufacturing in Exeter, New Hampshire. A native of Philadelphia, he had moved out of the family home in the late 1970s (His older sister, Sally, was living with her husband in Cape Neddick when Johnson first moved to Maine) to a cabin on Jewett Court, visible at the time from the Kittery Traffic Circle. A private self-storage center is there today.

At the end of the work day, he left to drive home. He didn’t come in to work or call in sick on Friday, Feb. 4, and didn’t make a customary weekly phone call to his family the following Sunday.

Cummer said the case notes indicate Johnson’s boss said Johnson quit, but the notes don’t indicate if Johnson actually said this to his boss, either by phone or in person. It’s possible, Cummer said, that Johnson’s refusal to show up was simply interpreted as quitting, as it was a blue-collar job with a lot of turnover at the time.

“I have no knowledge that he quit his job. The family didn’t know he quit his job,” Cummer said.

Even less clear are the events that followed Feb. 3. Within a 10-day period, Cummer said, the case notes indicate Johnson visited his bank to empty his account, then bought groceries at a store in Stratham, New Hampshire, which is next to Exeter. Johnson also apparently bought expensive thermal underwear at an outdoors supply store in that same area, and car stereo equipment at a local Radio Shack, all with checks written on an empty bank account.

Given Johnson’s history of financially responsible behavior, Cummer said, the notes describing the purchases seem strange. Especially puzzling are the food purchases, all from a supermarket miles from his home, as opposed to the local market he used to walk to for his weekly groceries. The food purchases totaled $146, or just over $395 in today’s value.

“For one guy? And it was so far away from where he lived?” Cummer said. “None of it makes a lot of sense.”

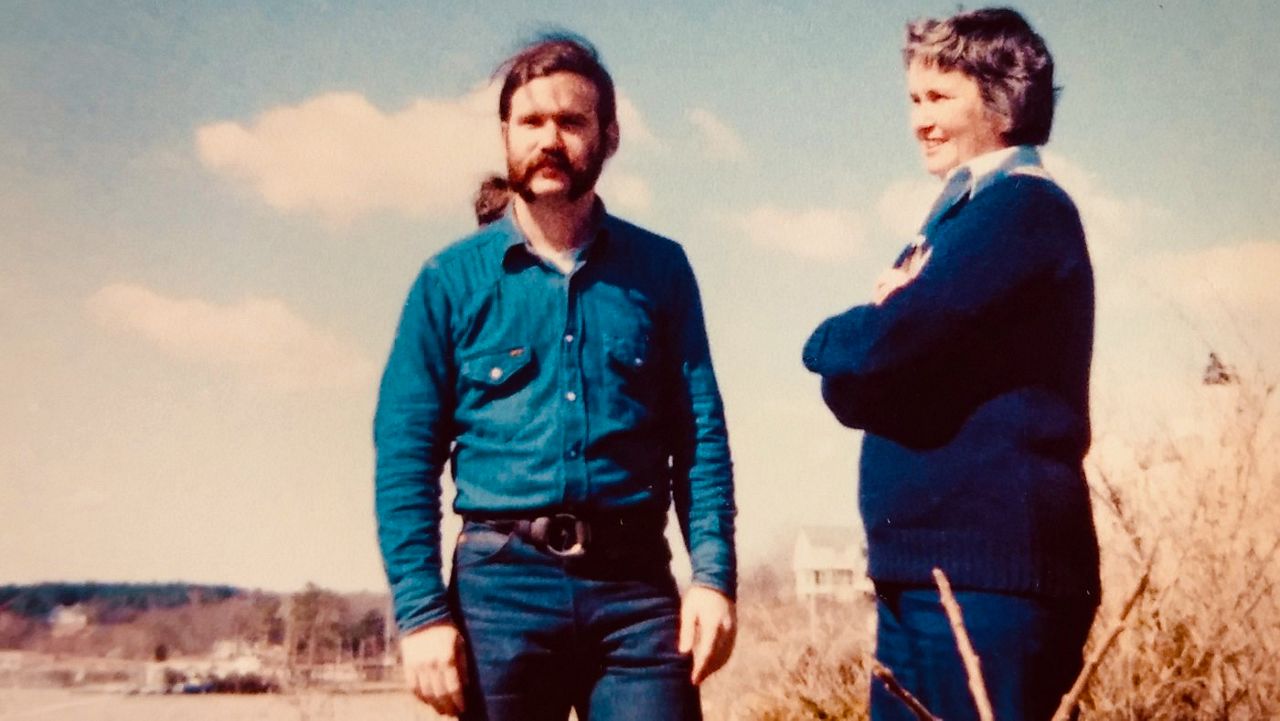

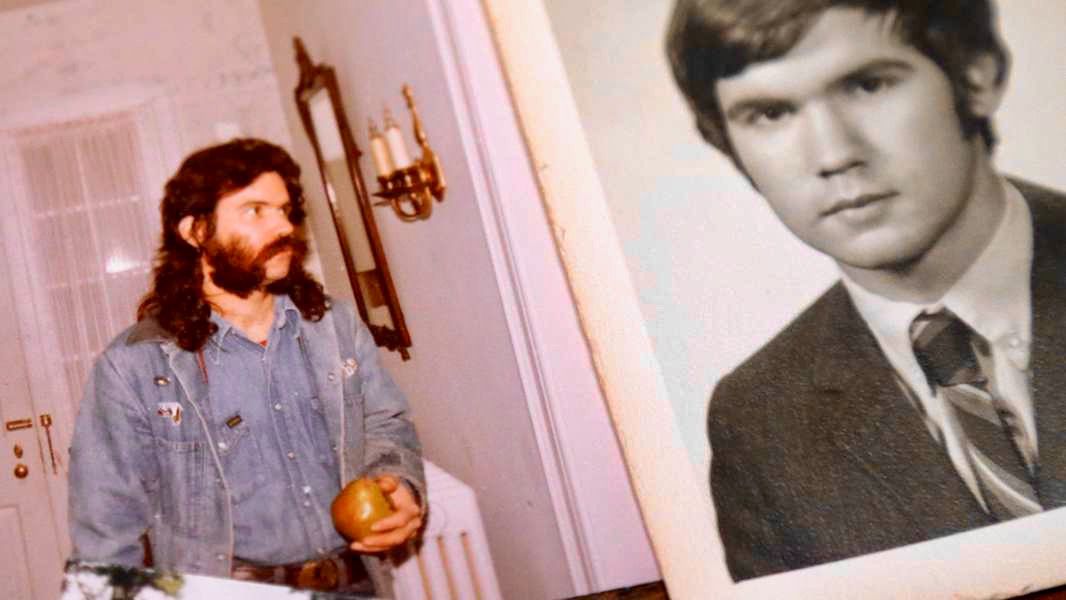

Cummer said Johnson’s appearance, with long hair past his shoulders and a beard, was common enough in 1983 that someone with a similar appearance could have been masquerading as Johnson and using his checkbook to make the purchases.

“Whoever was using the checking account drained it to the point that they were bouncing checks,” he said.

Finally, at the behest of family members, police in 1983 visited Johnson’s cabin on Feb. 15. Snow from a storm that hit the area on Feb. 6 — three days after Johnson was last seen working — remained undisturbed around the house.

“His cabin was completely cleaned out, and that probably happened before the snowstorm,” he said.

The door had been unlocked, according to reports, and Johnson’s pipes were frozen, but there was no outward sign of a crime taking place: No signs of forced entry or struggle, and no blood, but no sign of Johnson or his belongings either.

There is one clear sign that Cummer said leads him to believe someone else was involved in Johnson’s disappearance. It came shortly after Feb. 15, 1983, when someone claiming to be Johnson called Donnelly Manufacturing to ask that Johnson’s final paycheck be mailed to the Kittery-based post office box where Johnson got his mail.

Cummer said police could not spare the manpower at the time to stake out the post office, so Johnson’s parents, Barbara and Reeves K. Johnson Jr., volunteered, sitting in the post office’s lobby in shifts. One day, Barbara Johnson saw a man walk right up to her son’s post office box, open it with a key, and throw away all the mail inside except for the envelope with the check.

His mother, according to the case notes, confronted the man and asked where her son was. The man, who did not indicate his name, said Johnson was staying with him in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and took off running. Barbara Johnson snapped a photo of the man, but he held up his hand in front of the lens, making it impossible to see his face. She described him at the time as a white male, young, wearing green coveralls and a red hat. He stood about 5-foot-10, and, according to the notes, had long reddish-blond hair and “a clean and neat appearance.”

Cummer said one last potential clue is in the case notes — presumably from family members relaying information from Johnson himself — indicating that Johnson picked up a hitchhiker on Dec. 26, 1982, while he was on the way home from visiting family for Christmas.

The hitchhiker, who said his name was “Richard,” said he was headed for Detroit or Ontario, in the opposite direction Johnson was driving. Richard rode with Johnson anyway and Johnson, being a generous person, took Richard all the way back to his cabin in Kittery. Johnson let the man stay there for more than a week, even giving him food and money for cigarettes, until Richard arranged to have someone he knew from Massachusetts come pick him up during the day, while Johnson was at work, on Jan. 7, 1983, less than a month before Johnson disappeared. Cummer said police believe the man may have had a key when he left. Unfortunately, the notes don’t contain a description of Richard, or even an accurate full name.

“We don’t have any information about that guy,” he said.

The Maine State Police lists 75 unsolved homicides on its website, and the Charley Project, a website run by a nonprofit that tracks unsolved cases nationwide, lists 53 open missing persons cases, including Johnson’s, in Maine alone.

Seavey, as part of her podcast work, tracks and monitors cold cases, and was amazed when, upon reading a recent media account of the case, was unfamiliar with it.

“I had never heard of Reeves before, so it caught my eye,” she said.

Cummer said it’s possible that the case didn’t get more attention at the time because, even in 1983, people were far less connected to each other than they are today, and it was all too common for people to disappear for quite some time before returning to their lives unharmed.

“If somebody wandered off for a couple months, you might not think much of it,” he said.

Seavey agreed, noting that investigators at the time had no clear evidence anything was wrong at all.

“The detectives had no reason to believe that foul play had happened,” she said.

Seavey reached out to Cummer, and arranged to meet with him and Johnson’s sister, Sally, and younger brother, Hugh. Meeting the family, and seeing their anguish over not knowing what happened made her even more interested in telling Johnson’s story, she said.

“A missing persons case is a different kind of heartache than a typical cold case,” she said.

Cummer said he will continue to work the case, but he acknowledges that he is struggling against time, with witnesses no longer alive, businesses closed and other evidence lost.

“I’m hopeful but I temper that with the fact that the case is 40 years old, and a lot of the people who could have had information are no longer with us,” he said.

Johnson had brown eyes and dark brown hair, long enough to hang past his shoulders. His sideburns were connected to a moustache in nearly a full beard, with only his chin shaven. He is described as 5-foot-7 and about 130 pounds. He suffered from hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar. Johnson’s car, a red 1972 Volkswagen Beetle, was taken within days of his disappearance to Elwynn Park Exxon in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for unspecified repairs. It was never picked up.

Anyone with information about Johnson or his disappearance is asked to contact Cummer at 207-439-1638, or by email at bcummer@kitterypolice.com.