The state Department of Transportation has identified the Midcoast town of Searsport as a potential site to build a major offshore wind construction hub for projects in the Gulf of Maine.

In a study released Tuesday, MaineDOT says the state should begin talking with environmental regulators and federal agencies about next steps to plan and permit the Searsport project. They want to use it to build out the region’s fledgling floating offshore wind industry, and potentially compete with other offshore wind support sites that are in the works down the Atlantic coast.

The state says it expects to have a detailed public input process as it plans the “port-hub.” Another study will be released in the next few months on building out related infrastructure in the ports of Portland and Eastport, in far Downeast Maine on the Canadian border.

“The creation of a comprehensive port strategy could make Maine a premier hub for offshore wind development,” state Chamber of Commerce president Dana Connors said in a state press release. “Embracing this new industry, while preserving our essential fishing industry, will help drive economic growth and prosperity in Maine for decades.”

The new DOT study says Searsport, specifically Sears Island, was chosen as a potential nucleus of this industry because of its central location, available land and deep water — all needed to host the immense components and vessels that are used to build a wind farm at sea.

“We look forward to realizing the economic benefits of putting more port into Searsport, while we preserve the ecological and recreational aspects of what makes us special,” town manager James Gillway said in the release. “It is exciting to think that Searsport might play a role in the future of renewable energy thus reducing our country’s carbon footprint and contributing to actually saving the planet.”

Offshore wind is expected to be a major part of Maine’s climate change plans to sharply reduce its greenhouse gas emissions in the next few decades. The Biden administration also aims to approve 30 gigawatts of offshore wind in the U.S. by 2030 — roughly as much as is currently online, in total, throughout the rest of the world.

The Gulf of Maine’s deep water will require the use of even more cutting-edge technology: floating turbine platforms, which the DOT study estimates could be more than 300 feet wide. They would support turbine towers almost as tall as the Eiffel Tower, topped with blades that are each longer than a football field.

The University of Maine, an epicenter of research on floating wind, is working with Aqua Ventus to build the nation’s first floating offshore turbine off Monhegan Island. The state of Maine is also seeking federal approval to build a floating wind research array further offshore, about 45 miles southeast of Portland.

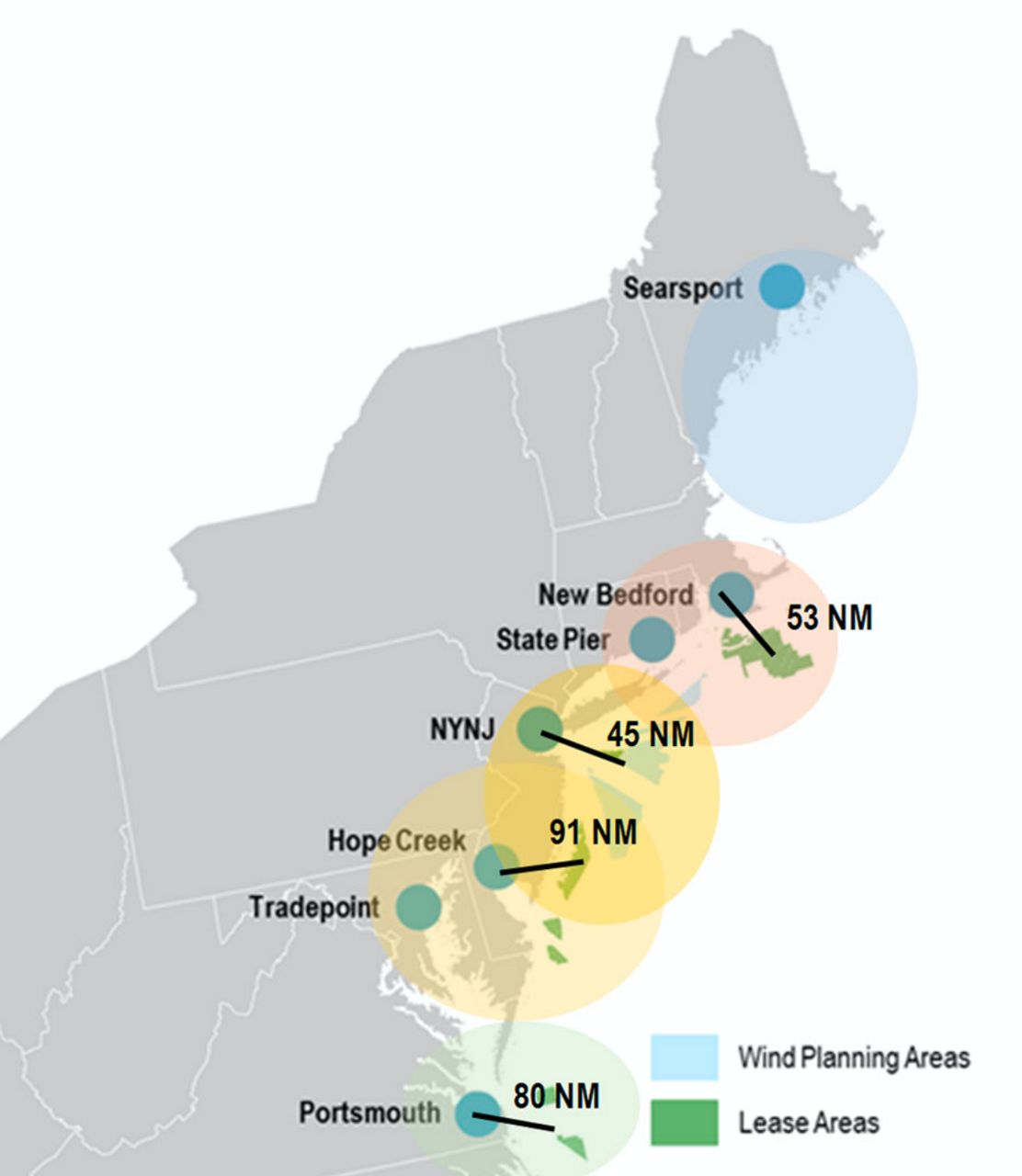

The DOT report says these state-waters projects and any future wind farms in federal waters off Maine will need to be staged out of a port that’s relatively close by — one where huge turbine components can be delivered by barge and bulk carrier, and towed out to sea for installation.

The study found the ideal port will need water that’s at least 35 feet deep, with room for vessels that could be up to 600 feet long and 400 feet wide, and no bridges or overhead wires between the shore and sea.

The facility will need upland space for storage and staging, plus dock space of between 500 and 1,500 feet in length, totalling between 40 to 65 acres. It will also need to be able to support the weight of turbine parts, heavy-lift cranes and self-propelled “crawler” transports.

The study identifies Sears Island, which links to Route 1 by bridge in Penobscot Bay, as an ideal site for such a port. The facility could also include some neighboring industrial facilities, including space at Mack Point within an existing Sprague Energy cargo terminal and tank farm.

Sears Island also includes a large conservation area. The state says it wants to support more use of that area as part of the wind hub planning process, potentially including a new education center, trailhead parking, better waterfront access, outdoor classrooms or other features.

“MaineDOT considered a whole island approach and acknowledged that if port development and investment were to occur on the transportation parcel, improvements could be made to the conservation area to improve the experience for visitors to the island,” the report says.

The report estimates it would cost a total of $283.9 million and take about six years to build out a two-phase wind hub at the site, starting out supporting research arrays and growing to support much larger, full-scale turbine farms.

The state expects this project, and the industry it will support, to become reality by the late 2020s or early 2030s. Right now, there are no federal wind leasing areas in the Gulf of Maine.

The state is in the early stages of that planning process with its neighbors New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Governor Janet Mills has asked the U.S. Interior Department to reconvene that tri-state task force, which met only once, just before the pandemic, in December 2019.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the state was developing a research turbine array near Vinalhaven. In fact, the array is planned about 45 miles southeast of Portland. This story has been updated.