In some ways, the Machias causeway is Erik Kidder’s office.

For the past 15 years, he’s sold collectibles and knives from his vehicle to passersby on U.S. Route 1. Other vendors use the causeway too, and town officials hope a revitalized space will draw other economic drivers, such as food trucks. Maybe the rusty guardrails will be removed, trees will be planted and restrooms will be available for those using the Down East Sunrise Trail that links Ellsworth to Calais.

Machias officials want the causeway to be a focal point — a key to the town’s revitalization.

“The causeway is one of the most visible and accessible signature assets we have and one of our greatest opportunities for public engagement,” Town Manager Bill Kitchen said. “It has so much potential to be a working commerce hub, and a stunning public and recreation space, for both our communities and our visitors.”

For that to happen, federal, state and town officials must balance a long list of competing needs: salmon and other fish that swim under or through the causeway; water that could cause flooding; stronger storms and heavier rain that contribute to sea-level rise; current and future community use.

As it is now, the wood and stone masonry box culverts with four flappers that should let fish pass between the Machias River and the Middle River have deteriorated. The flappers are hinged gates on the Machias River side of the causeway that restrict the upstream flow of seawater and allow the downstream flow of fresh water, said Dale Doughty, director of public outreach and planning at the Maine Department of Transportation.

But the flappers are no longer working properly and are just one of the issues with the causeway, which was built mostly on what Doughty described as “rubble.”

“It’s near the end of its useful life,” he said.

The department is considering several options, including repairing what’s there, replacing the culverts or replacing the whole system with a bridge. By mid-spring, they hope to identify the most likely solution, but will then need more time to study it. It will be a couple of years before a final design is completed – and there will be plenty of time for public input, he said.

Local residents offer differing opinions about what should happen.

“I think they ought to open up the flapper and let the water go up through,” Kidder said on a recent chilly and gray morning.

But for Chris Sprague, who owns 90 acres in nearby Marshfield, that would be the worst possible outcome.

“I think it’s horrific for them to change what’s there,” he said.

Sprague acknowledges that a section of the causeway needs to be fixed but says he’s spoken with biologists who don’t think the Middle River is a major salmon habitat. Without something to hold the water back, he estimates 82 acres of his land will be underwater.

“It’s a unique habitat,” he said. “It would be a shame to lose it just because they want to flood it out.”

For nearly 20 years, the Downeast Salmon Federation has been interested in seeing a bridge replace the causeway in Machias and one of similar construction in nearby Addison, executive director Dwayne Shaw said.

“The two of them together total 700 acres of potential saltmarsh restoration opportunities,” he said.

Twelve species would benefit from a bridge, including sturgeon, salmon, smelt, eel, striped bass, shorebirds and waterfowl, he said. In addition, the design of whatever replaces the causeway needs to take into consideration “climate-related weather and flooding events,” he said.

“The whole causeway needs to be elevated because of sea level rise,” he said.

The Downeast Coastal Conservancy is another of the groups that would like to see a bridge replace the causeway, but officials acknowledge that there are a lot of things to consider.

“We’d like to see the flow of the river restored,” said Jon Southern, executive director of the group. “We don’t know enough about a proposed bridge to evaluate the impacts of that solution.”

One person who hopes that local voices don’t get ignored is state Rep. William Tuell (R-East Machias), who submitted a bill to the Legislature to require local approval of the causeway replacement project. A bipartisan group of legislative leaders on Monday rejected it – typically bills considered in the second year of a two-year session are supposed to be an emergency – but Tuell plans to appeal the decision next month.

He said residents in Marshfield and Machias should be able to vote on the transportation department’s final proposal.

“The project has always been controversial,” he said. “Critics will say it’s a done deal. The best way to solve that is to have a vote.”

The project dates back several years, with the Maine transportation department announcing in 2018 that it preferred to replace what’s already there. But in 2020, the National Marine Fisheries Service objected, saying it would not improve habitat for Atlantic salmon, rainbow smelt, alewife and blueback herring.

“The preferred alternative is, in effect, a proposal to reconstruct a dam that will block fish access into the Middle River watershed for the next 75 years,” wrote Julie Crocker, endangered fish recovery branch chief.

Doughty said the state is now considering the impact of each alternative. In addition to complying with the Endangered Species Act – Atlantic salmon are on the list – they also have to consider impacts on property owners and on any areas of historical significance. For example, he said there’s an old horse racetrack that would be partially or totally flooded if a bridge is put in.

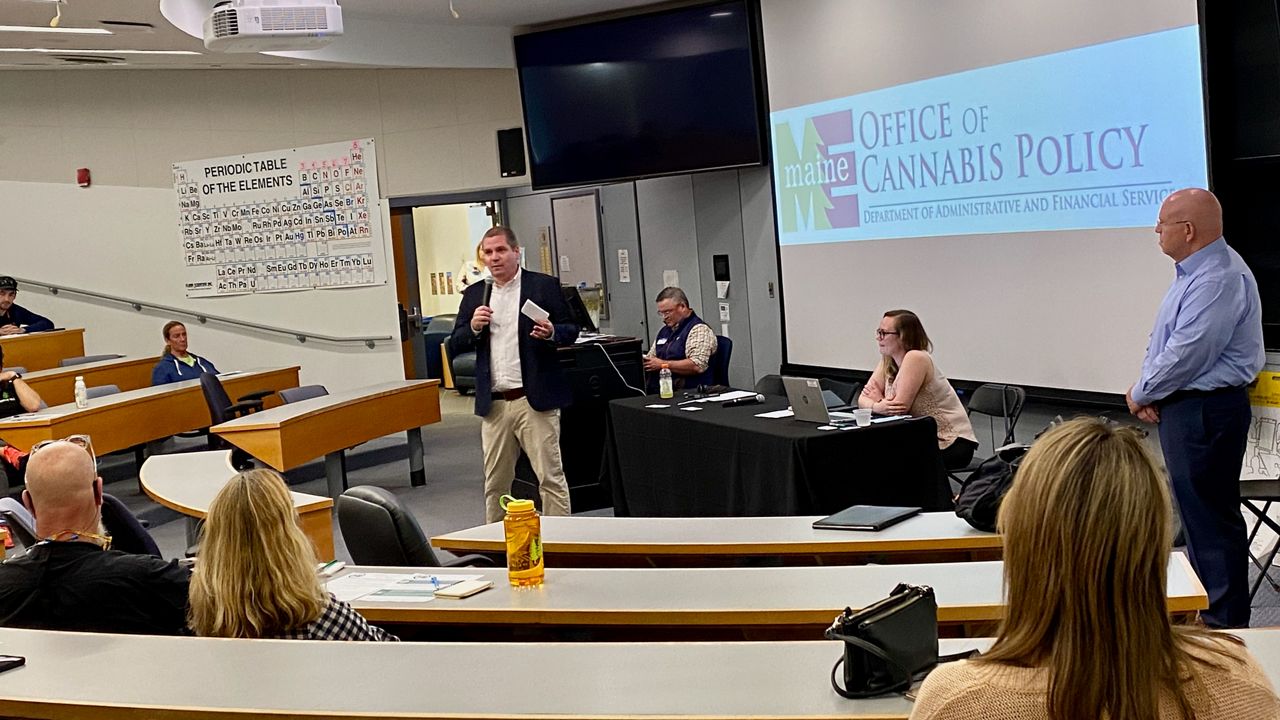

And, after more than 100 people attended an informational meeting on the causeway last month, they are very much aware that it is an important part of Machias. Kitchen, the town manager, said they want to work closely with the state.

“Our goal is to make this MDOT’s ‘poster project’ of partnership, using infrastructure improvements to significantly impact the revitalization of a critical coastal community and its cultural and economic development,” he said.