The future of a Skowhegan landmark is in limbo following a decision by the town selectboard not to accept it as a gift, citing costly repairs they say the town can’t afford.

Earlier this year, the Skowhegan Region Chamber of Commerce asked the selectboard to take ownership of the Skowhegan Indian, a 62-foot-high Bernard Langlais sculpture, after it sustained significant damage.

Skowhegan Town Manager Dawn DiBlasi said the selectboard decided it could not afford the estimated $100,000 in repairs.

“We really don’t have the money to fix it and keep it up,” she said. “It’s not easy. A lot of people love that Indian.”

The sculpture is one of about 20 Langlais creations on display throughout Skowhegan as part of what’s described as “a whimsical art walk.” The town office, public library, community center and grist mill all feature works by the artist, including “Girl with Tail” a large mermaid in the riverfront parking lot.

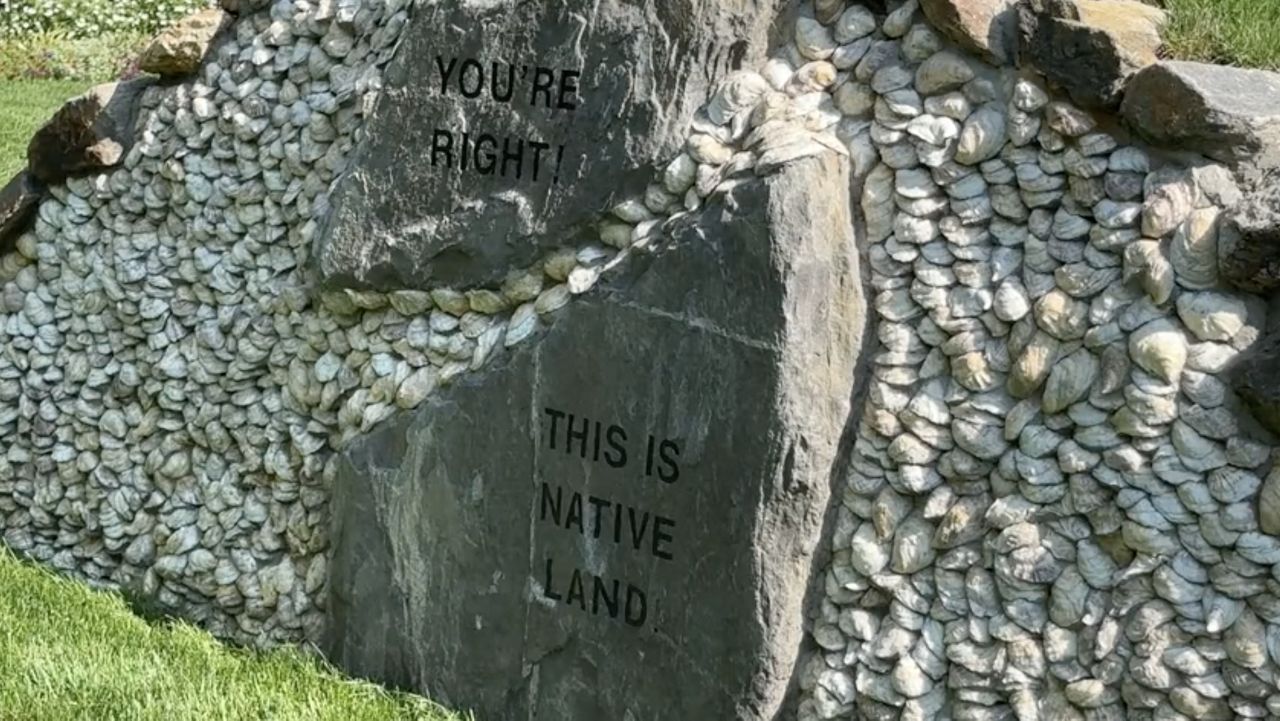

The uncertainty over what to do with the sculpture comes just five years after the town went through a heated debate over its high school mascot. The school board voted 14-9 in 2019 to stop using Skowhegan Indians as a mascot, the last school district in the state to do so.

More than a year later, the local school board chose the River Hawks as a new school symbol.

Penobscot Nation Tribal Ambassador Maulian Bryant, who served on a committee to encourage the school district to change its mascot, said she doesn’t feel strongly one way or another when it comes to the Langlais’ sculpture.

While spending time in Skowhegan during the school board debates, she said she noticed that many in town have a strong connection to the artwork.

At the time of its dedication in 1969, the chamber said the sculpture intended to honor “the Maine Indians, the first people to use these lands in peaceful ways.”

Born in Old Town, Langlais left Maine after high school to study commercial design in Washington D.C., according to the Langlais Art Preserve.

He spent three summers at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, trained at the Brooklyn Museum School and received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in Norway.

After time spent painting in New York City, he moved back to Maine in 1966, settling in Cushing.

That same year, the Skowhegan Tourist Hospitality Association commissioned Langlais to build the Indian sculpture, which is a steel structure with a wooden exterior.

The sculpture originally depicted the Indian holding a spear in one hand and fishing weir in the other.

“At the time of Langlais’ death in 1977, his outdoor art environment comprised well over one hundred wood reliefs and three-dimensional pieces, including more than sixty-five monumental sculptures,” according to the preserve’s website.

They described the Skowhegan Indian as Langlais’ “most widely publicized work.”

Today it stands in a municipal parking lot off Madison Avenue and High Street, a block north of the downtown. Visible damage includes wood missing from the bottom half of the Indian’s face and a missing left hand. His fishing spear is gone too.

About 10 years ago, the chamber and the Skowhegan Indian Restoration Committee spent $65,000 to restore the sculpture, which is made mostly of white pine.

According to the chamber, it is “the tallest sculpture of its kind in the world” and is one of the few Langlais pieces to remain in its original location “which is very important to art investors, foundations, and art historians.”

Moving forward, the chamber is asking for volunteers to serve on a new committee “to determine the future of the Skowhegan Indian,” according to a June 25 newsletter.

The chamber did not respond to multiple requests from Spectrum News for information regarding the sculpture.