Cedar Brook Burial Ground, located on a three-and-a-half-acre segment of Joyce Foley’s property in Limington, doesn’t look or feel like a cemetery at all and, she said, that’s the point.

“It’s wonderfully peaceful here,” Foley said.

During a visit on Monday, the non-denominational cemetery was covered by a canopy of trees and several inches of winter snow, looking more like a dirt path through the woods than a traditional, manicured, orderly burial ground.

The private cemetery’s natural, simplistic approach is just one of hundreds of burial grounds established over the last few decades worldwide in a movement described as “green burials.”

Driven by an environmentalist’s philosophy, the concept involves avoiding putting anything into the ground that can cause unnatural contamination of local soils, according to the Green Burial Council, a California-based association dedicated to the subject.

According to the council’s website, green burials are done without embalming the body. They also don’t involve vaults or caskets made out of metal. Even wooden caskets are made with simple woods that haven’t come from rainforests and are often unfinished.

“When they have done water-testing studies in conventional cemeteries, the contamination that they find is not dead-body stuff but toxins from furniture, which would be the glues and the varnishes and the stuff that’s coming off of the caskets,” said Gretchen Spletzer, administrative coordinator for the council.

The council cited data from a Cornell University study that shows in a typical year, traditional burials use “4.3 million gallons embalming fluid, 827,060 gallons of which is formaldehyde, methanol, and benzene; 20 million board feet of hardwoods, including rainforest woods; 1.6 million tons of concrete; 17,000 tons of copper and bronze; 64,500 tons of steel.”

Spletzer said the movement also hearkens back to simpler times before the mid-19th century, when more formal burial practices began.

“Green burial is actually how we used to bury our dead before we had a funeral industry,” she said.

The exact origins of the modern green burial movement are unclear, but Spletzer said the council was first established in 2005, and inspired by the Natural Death Centre, an organization in the United Kingdom dating back to 1991. According to its website, the British group today has maps of more than 270 “natural burial grounds” in the UK. A 2021 study of the global green burials industry by market research firm Emergen Research estimated more than 16 countries worldwide are conducting green burials.

The council estimates there were more than 350 green burial sites in the U.S. as of March 2022.

The council also noted a 2022 report from the National Funeral Directors Association that indicated just over 60% of consumers surveyed were interested in green burial options, up from just over 55% in 2021.

“It’s growing,” Spletzer said. “The movement’s growing a lot.”

Foley said she and her late partner, Peter McHugh, lived together on the 140-acre Limington property starting in 2000, he a retired industrial carpet salesman from New York, she a Maine native and retired phlebotomist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

She said McHugh was inspired to create the cemetery after reading an article in the Boston Globe on the subject.

“He thought, ‘Wow, if I do this, it’s something new and interesting,’ and it was a challenge to him, too,” Foley said.

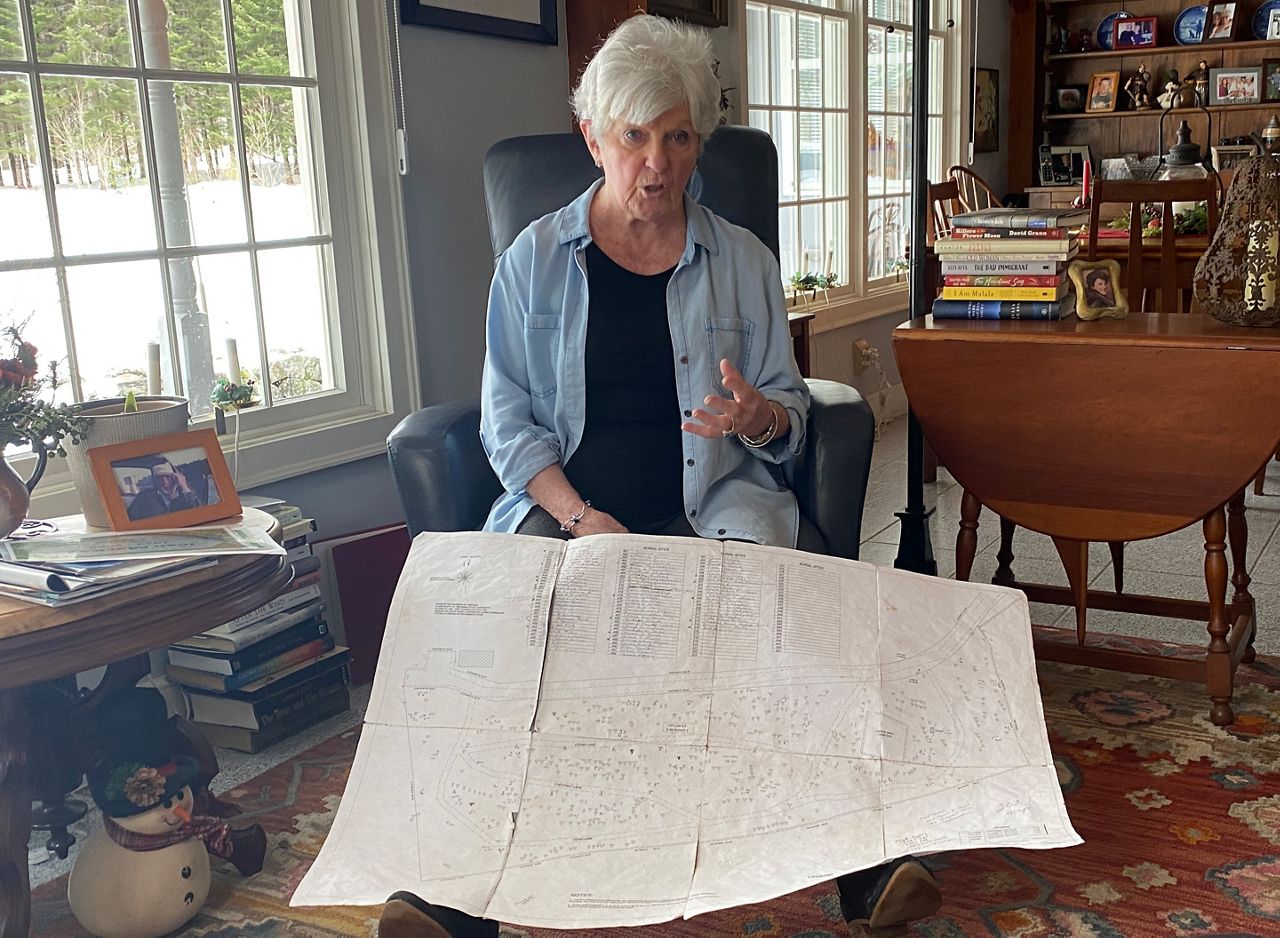

From there, the couple went through a simple process of surveying the 3.5 acres and registering the land as a private cemetery with the York County Registry of Deeds. Foley said Cedar Brook Burial Ground follows all state regulations pertaining to burials, and deeds to each of its plots are notarized at Limington Town Hall.

Anchored by a small family cemetery established by the property’s previous owners, the cemetery has virtually no obvious markers for gravesites. Even the gravestones are small and flat, no larger than a turkey platter, Foley said.

They lay on the ground, which makes them impossible to find in the winter without a map that Foley provides visitors. Even in the warmer months, she said, groundskeeping is at a minimum, leaving visitors feeling like they are taking a walk in the woods rather than visiting a cemetery.

“Somebody who didn’t know, unless they got out of their vehicles and walked around and saw the stones, they wouldn’t know there was a cemetery here,” she said.

The no-frills approach is less expensive, with individual plots costing no more than $800. Stones are free, Foley said, with engraving offered by a local artist for $100.

An exact average cost of a public cemetery plot was not available, but estimates from various insurance companies and consumer groups online suggest plots can cost as much as $2,000.

Foley said price and the cemetery’s natural, environmentally-friendly approach have been attractive. Since first registering in 2007, the burial ground has established 515 gravesites, including McHugh’s (he passed away in 2013) and Foley’s own, which will be next to his.

Foley said there are plans in place for the cemetery to continue long after she is gone. The property may be sold, she said, but legal mechanisms will ensure that the cemetery will be maintained and undisturbed, a permanence and quiet that befits its purpose.

“There’s a peace that’s here,” she said.