Two Maine towns, Kennebunk and Presque Isle, while more than 250 miles apart, have at least one thing in common. The communities are seeing a rise in homelessness, bucking the notion that homelessness in Maine is limited to urban areas.

“At any given time we have 50-plus people that we’re facilitating, feeding, housing,” said Brad Summerlin, residential service manager at Homeless Services of Aroostook in Presque Isle.

The shelter is more than 150 miles north of Bangor and more than 280 miles away from Portland, Maine’s largest city.

Summerlin and Edward Begos, the shelter’s housing navigator, said it is the only one of its kind north of Bangor, and services a county that is Maine’s largest in area, but most sparsely populated.

Despite its remote location, an influx of homeless people over the past five years alone has forced Homeless Services of Aroostook to expand. Summerlin said the shelter went from a capacity of roughly 17 in 2019 to its current capacity, which includes 49 beds and a warming shelter that accommodates as many as 12 to 15 people.

In the average year, he said, the shelter serves 1,000 people.

Even that doesn’t appear to be enough. When asked how often the shelter is at capacity, both Summerlin and Begos said, “All the time.”

Permanent housing of any kind remains at a premium locally. Begos said the Presque Isle Housing Authority, which is currently trying to find one-bedroom apartments for single adults, has a waiting list of more than 100 people.

As to why, Begos and Summerlin said part of the problem lies in an influx of people becoming homeless due to the coronavirus pandemic costing residents their jobs.

Begos added that people moved to the area during the pandemic, seeking a quieter and safer life, but they arrived only to find there was no place for them to live.

“The allure of having work up here for people to do it doesn’t coincide with the available housing market, and so people come up here thinking they can just get a job and get an apartment, and there’s no apartments,” he said.

Sometimes, he added, homeless people in more densely populated areas migrate northward.

“We get a lot of folks from Bangor,” Begos said. “When the Bangor shelter’s full, they get sent up here, if we have an opening.”

The shelter can only accommodate 22 people at a time with sobriety problems at a time, but he said as many as nine out of every 10 people the shelter serves have some sort of mental health or addiction issue.

“I truly believe that mental health is probably the number one if not number two reason why people do end up experiencing homelessness,” Summerlin said.

Farther south, in York County, away from more urban centers such as Sanford and Biddeford, the small, affluent coastal town of Kennebunk also finds itself wrestling with homelessness.

The Kennebunk Police Department’s Behavioral Health Unit started tracking homelessness locally in 2022. According to the unit’s data, from July 2022 through November 2022, the unit was aware of 13 homeless people in town. A year later, that number increased to 17 over the same period.

Police officers in Kennebunk, the data showed, are interacting with the homeless more often. From July through November 2022, there were 40 encounters reported. That number went up to 141 in 2023, an increase of 253%.

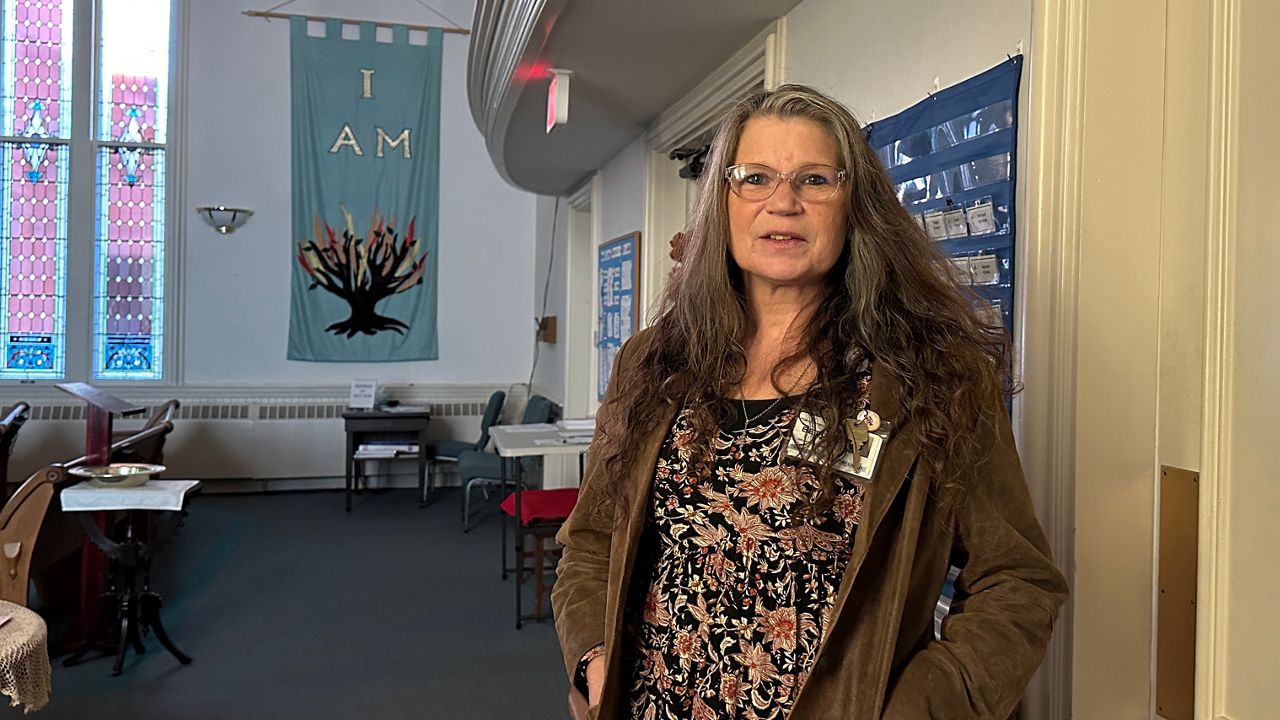

Karen Winton is the town’s deputy director of community development and has worked as a general assistance coordinator in Kennebunk for the past 10 years.

She said she remembers when Kennebunk had long-term rental property owners, whom people in her office could often turn to for temporary housing for the homeless.

Changes in the housing markets, however, have led to property owners converting to more popular short-term rentals, or selling their property off altogether, leaving Winton with fewer options now.

“That has completely dried up. That landscape is totally different,” she said.

Winton said one sobering statistic was the growth in general assistance spending. From 2022 to 2023, she said, spending went up by $27,825, a 375% increase. All of that, she said, was related to finding temporary housing for people in hotels or motels.

“That’s how we knew that the numbers were really increasing was over that last year, that spike in spending on the temporary housing piece,” she said.

Like Presque Isle, Winton said many local homeless people come from Biddeford, Sanford or even Portland, an indicator of a lack of housing options in more urban areas.

“It’s spilling over from other communities,” she said. “When you have people forced out of larger cities where there used to be this availability, and they’re coming south, or they’re coming east, wherever they’re coming from, it’s because it’s regional. All around us, there’s a housing shortage.”

HARDER TO GET AROUND

In Kennebunk and Presque Isle, simply getting from one place to another is a challenge. Unlike larger cities, there is little to no public transportation.

In Presque Isle, Begos said there is one cab company, and it’s way too expensive for a person on a fixed or low income. That puts a lot of things, from jobs to apartments, out of reach.

“If you just had a car, you could find a place outside of Presque Isle, an apartment,” he said.

Summerlin said walking can work for some, but not in mid-winter, when temperatures routinely fall below zero.

“One mile seems like 25 miles,” he said.

In Kennebunk, Winton said there are some volunteer programs here and there, but few enough options to make distance a barrier there, too.

“A mass-transit system requires planning and congregation of people getting to a stop and then moving throughout town,” she said. “It doesn’t lend itself in this community to mass-transit, so you have to get creative.”

Winton and Summerlin both said local community leaders and the public have been supportive, but ongoing public education is key to coming up with new ways to solve the problem.

“We do have to get used to seeing things we’re not used to seeing in Kennebunk, which is people who are living out at our rest area,” Winton said. “They might see more transients in town, they might see people congregating in parks and various open spaces that they might not have been sued to seeing in the past.”

Summerlin said there’s also the ongoing battle against the stigma the public has about the homeless.

“They need to understand that these are people who are just trying to find community,” he said. “They’re just trying to find a home. They’re just trying to be a part of something.”