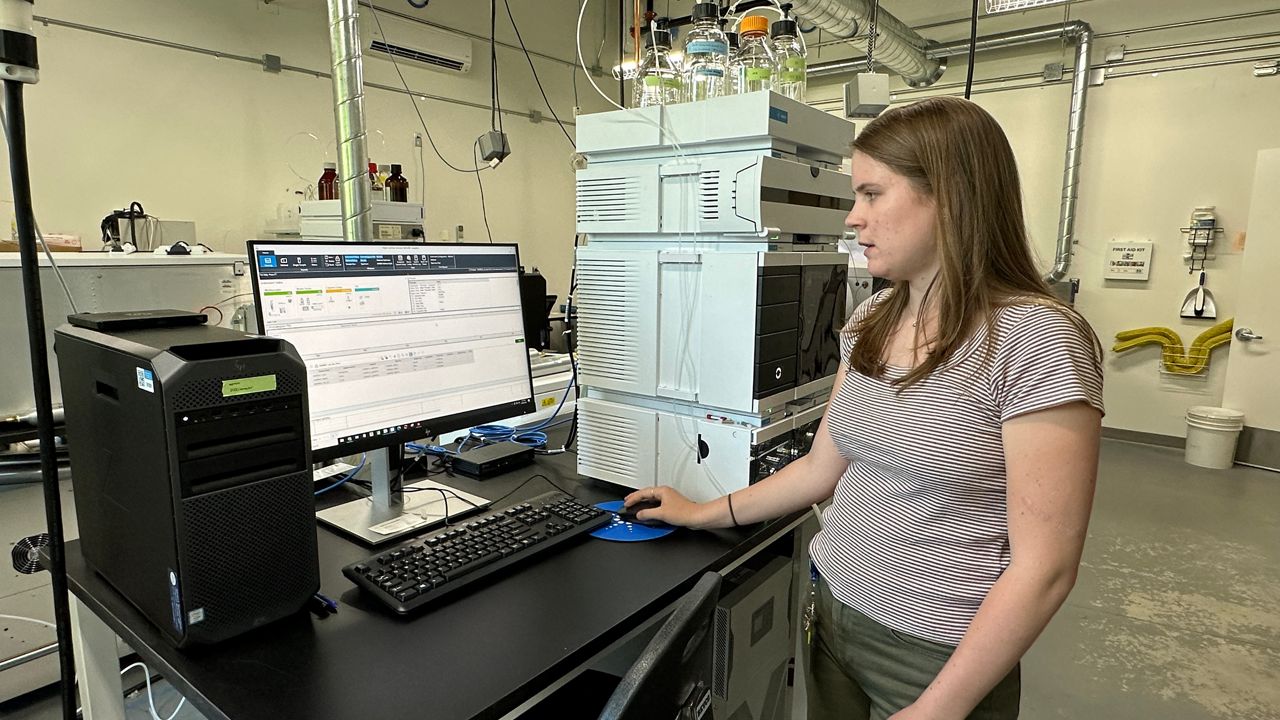

A lab with the ability to find “a pinch of salt in an Olympic-sized pool” is turning its powerful science toward PFAS, the forever chemicals that contaminate farm fields and drinking water in many parts of Maine.

Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences is just the third PFAS testing center certified by the state to look for the chemicals in water, sediment, soil and tissue samples.

Senior Research Scientist Christoph Aeppli said Bigelow wants to contribute to state efforts to track the scope of the PFAS problem — and use their expertise to eventually guide solutions.

“There is a need in Maine to have testing capacity,” he said. “Maine has been really progressive in tackling the PFAS problem and getting data out, but it also means there’s a lot of testing that needs to be done.”

That work includes samples from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, which examines farm fields where potentially contaminated sludge was spread or wastewater samples. Private homeowners can also send in samples, with costs for a comprehensive test ranging from $400 to $700.

The term PFAS covers thousands of chemicals that repel oil, grease, water and heat. They were used for decades in non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpets, furniture, food packaging and thousands of other products.

The chemicals have been linked to thyroid disease, pregnancy-induced hypertension and three kinds of cancer — kidney, testicular and breast, according to the state PFAS plan.

Testing for PFAS is just one way the state is trying to tackle a problem that first emerged in 2016 on an Arundel dairy farm. That raised alarm bells about the common practice of spreading treated wastewater sludge on farm fields, which dates to the 1980s.

Since the 2016 discovery, PFAS has been found on about 60 farms across Maine and in public and private water supplies.

Lawmakers in 2022 outlawed the spreading of sludge on farm fields and created a $60 million fund to help farmers who may need to sell their land, take remediation measures or seek medical attention because of their exposure to the chemicals.

Maine has also taken aggressive steps to ban the sale of products containing PFAS, although the widespread use of the chemicals in everything from makeup to cars to tents has made it difficult to regulate.

Aeppli said he understands homeowner concerns about PFAS and hopes that further study will put the problem into perspective.

“I think there’s a lot of notion, that it’s forever chemicals and it’s everywhere and people may be a little bit despaired,” he said. “But I really think what can help is just having data, like knowing how big is the problem?”

Bigelow is an independent, nonprofit research institute in East Boothbay primarily focused on global ocean health. The other two PFAS-certified labs in Maine are Katahdin Analytical Services in Scarborough and Maine Laboratories LLC in Norridgewock.

In March, Bigelow released a study that showed that while PFAS is present in Casco Bay and is widespread, it’s not at “an alarming level.”

They are now turning their attention inland, hoping to add to the statewide dataset to help focus on the areas most impacted and identify solutions.

Aeppli said when it comes to well water, filters are already commonly used to remove the harmful chemicals.

But for someone who buys a farm with contaminated soil, more research is needed to find the most effective way to remove the PFAS, he said.

“I think science is really important here, to play a role to help bring it to the next level, to bring about solutions,” he said.