SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — Miguel Torres is the archetype of what might be called the Chilean dream.

A college dropout, he nonetheless rose above his working class roots thanks to decades of economic stability and Asian Tiger-like growth to build a successful career as the owner of a small outdoor advertising business.

But in the runup to Sunday's presidential election, the 68-year-old has been attempting the previously unthinkable: to sell the spacious home he built with a lifetime of hard work. While he doesn't have any offers, if he is lucky enough to find a buyer he plans to stash the proceeds abroad and downsize.

“I’m too old to leave the country,” he says, surveying the pool and giant camellia trees that adorn his home in the tony Los Condes neighborhood of Santiago, the capital. “But I’m not going to leave what little money I have here.”

Torres isn't the only Chilean on edge.

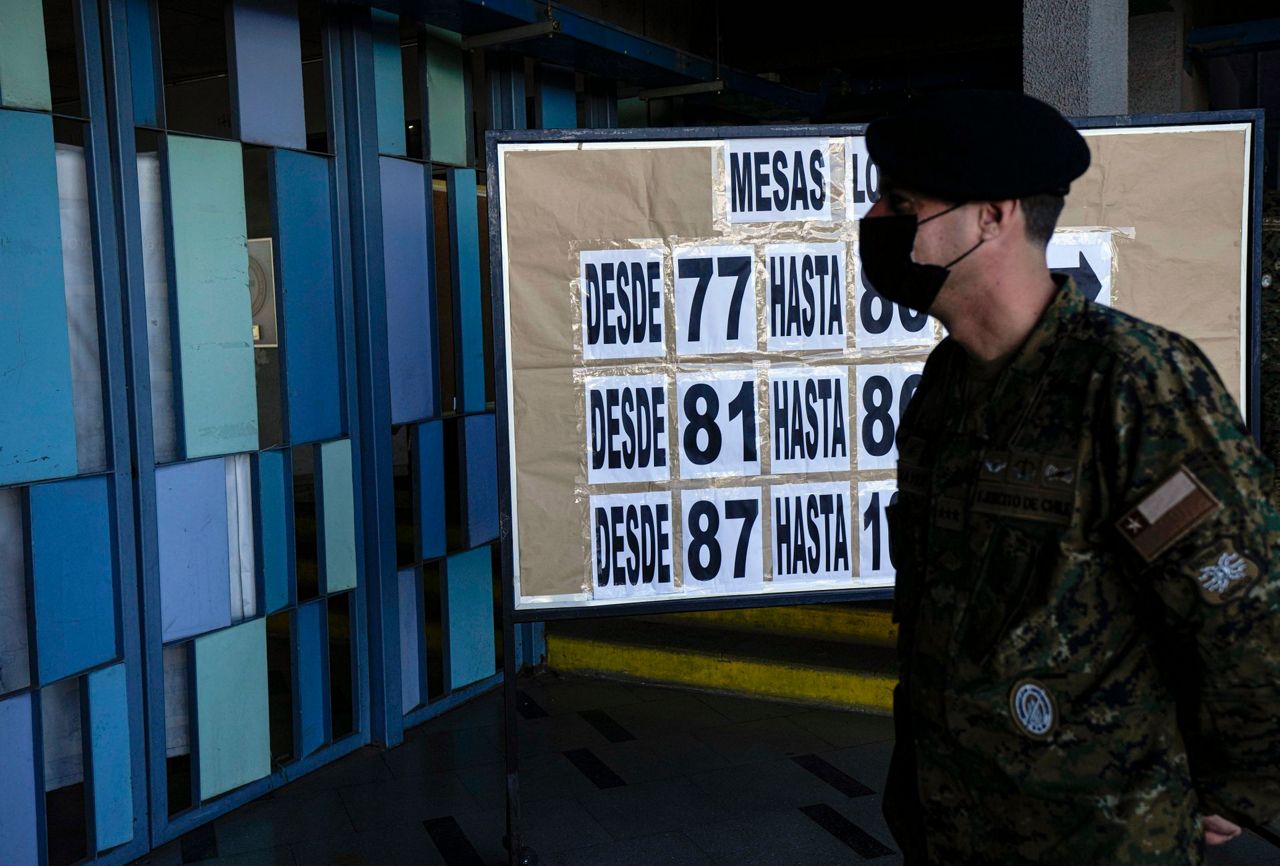

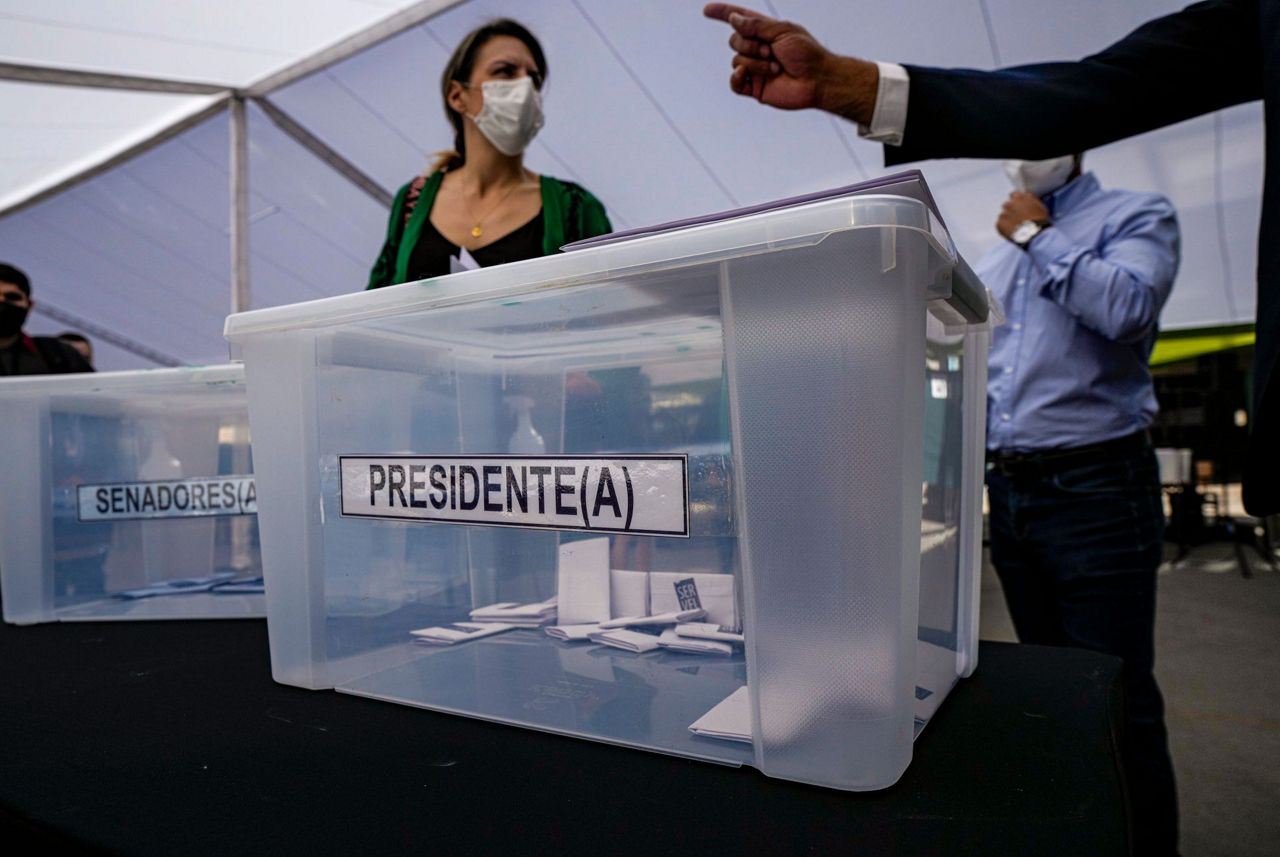

After an intense wave of social and political unrest in recent years that includes the current effort to rewrite the constitution, Chileans are heading to the polls with a mix of dread, optimism and above all uncertainty about what lies ahead.

The country has long stood in sharp contrast to its chaotic neighbors such as chronic debt-defaulter Argentina to the east or, to the north, Peru, which has seen five presidents since 2018.

But there is growing frustration with the free market model and its inability to root out nagging inequality and deliver affordable, quality public services in the country of 19 million people.

Polls consistently point to two frontrunners neck and neck ahead of all others in the seven-candidate race, though neither has been close to the 50% threshold needed to avoid a December runoff.

One contender, Gabriel Boric, is a 35-year-old former protest leader who has formed an alliance with the Communist Party and promises to “bury” Chile's past as a model of neoliberalism — a jab at the reforms imposed in the 1980s by Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

The other, José Antonio Kast, is a previously fringe candidate from Chile's far right who has a long history of defending the dictator's rule and attacking what he calls Chile's “gay lobby."

In the runup to the vote, Chileans like Torres have been voting with their wallets, opening dollar-denominated bank accounts and shuttling their savings abroad in the time-tested manner of their neighbors in Argentina.

Capital flight by non-corporate businesses and households surged to $29 billion in the 12 months ending in September, a jump of nearly 70% from the outflows reported a year earlier. Bond prices and the peso have also fallen sharply.

“To see political risk driving behavior to this extent is very new in Chile," said Jonah Rosenthal, an economist specializing in Latin America at the Institute of International Finance, a Washington-based trade group representing major international banks. "For Chileans with capital, there’s no roadmap to navigate uncertainty.”

Reflecting Chile's recent upheaval, and South America's increasingly polarized politics, the two main candidates are a study in contrasts.

Boric, who was brought up in the vast Patagonia region where his Croatian ancestors settled, rose to prominence as a leader of protests a decade ago demanding higher quality and less expensive education. Like a bevy of other student activists, he was elected to congress in 2014, noted for his informal dress, hipster tattoos and at one point even a Mohawk.

He dismissed criticism that he was snubbing protocol, calling such things “a tool of the elites to distinguish themselves from the low people.”

The Broad Front he heads is modeled on a leftist coalition of the same name in Uruguay and has proposed to raise taxes on the “super rich” to pay for expanding public services and protections for the environment.

He also wants to eliminate Chile’s privatized pension system — a hallmark of the Pinochet years that successive democratic governments were reluctant to touch despite growing evidence that the employee-only funded plan leaves masses of working class Chileans without enough to retire on.

Kast is the son of a German who served in Hitler's army during World War II and them migrated to Chile in the 1950s. An open admirer of Brazil's far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, his newly formed Republican Party seeks to cut corporate taxes and government red tape.

He has run a mostly law and order campaign that has stoked divisions on social issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights, immigration and the role of religion in schools.

He is also highly critical of Chile's outgoing president, fellow conservative Sebastian Piñera, for reaching agreement with his political enemies — among them Boric — to rewrite the Pinochet-era constitution in the wake of huge protests triggered by a hike in Santiago's subway fares.

If elected, Kast could butt heads with the left-leaning assembly that is drafting the new constitution and which, in theory, could cut short the next president's term.

In true Chilean fashion, both Boric and Kast have tried in the final stretch to play down their past radicalism, hoping to attract moderate voters who make up the bulk of the electorate — a trend that would likely continue in a runoff scenario.

But many Chilean are not convinced, even if a late surge in the polls by Kast — whose brother was one of the University of Chicago-trained economists who designed Pinochet's economic reforms — has somewhat calmed market jitters.

“As much as Boric tries to make substantial changes to his campaign platform, he'll have the Communist Party next to him and they won't let up,” said Juan Sutil, the owner of a major food conglomerate and head of the influential Chamber of Commerce and Production.

Torres, who has already started to transfer some of his savings into U.S. dollars, also worries that pressing social demands will end up weakening Boric's hand with his Communist allies.

“They are going to steamroll him,” Torres says.

But others say Chile, uniquely in a region wracked by turmoil, is properly channeling discontent.

Sergio Bitar, who served in the socialist administration of Salvador Allende that was overthrown by Pinochet as well as several center-left governments since, said the myth of the Chilean “economic miracle” died long ago. In indicators such as household income and poverty, the country lags far behind its peers in the Organization for Economic Development, a group of the world's 38 most advanced countries.

He nonetheless regrets that Boric and his supporters have chosen to focus much of their indignation at old timer moderates like himself.

“Let's hope the youth don't commit the same mistake as us in underestimating the right,” said Bitar, who was forced into exile for years after being imprisoned by Pinochet in the 1973 coup.

He said that while every generation tries to shatter the status quo that it inherits, political leadership requires compromise as well as idealism.

“Politics is the art of what's possible," said Bitar, who fears Chile's best years may be behind it and the country could slip into a malaise of mediocrity seen elsewhere in the region. "Without governability there can be no progress."

___

Joshua Goodman reported from Miami.

___

Joshua Goodman on Twitter: @APJoshGoodman

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.