If you’re trying to translate a weather forecast from English to Spanish – or anything, for that matter – you just translate the words and phrases, right?

Unfortunately, it’s far from a simple plug-and-play into Google Translate. In particular, translating weather terms and sayings from English to Spanish is especially challenging for a laundry list of cultural and language-driven differences.

But one group is trying to bridge that long-standing divide and provide improved resources – and ultimately, better weather forecasts and messaging – for the Spanish-speaking community.

Earlier this year, the American Meteorological Society (AMS), one of the country’s leading meteorological organizations, created a new committee exclusively dedicated to helping organize the growing community of bilingual meteorologists and improve weather outreach to the U.S.’s sizable Latin American population.

“The AMS Latinx committee strives to create a space for bilingual scientists,” said Joseph Trujillo, the head and founder of the committee. He's also a Graduate Research Assistant with the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies supporting the NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory and the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center.

“By 2060, there will be more Spanish-speakers in the U.S. than anywhere else in the world other than Mexico," said Trujillo. "It’s important for us to diversify and better collaborate with and reach these communities.”

Thanks to the committee’s early work, two English-Spanish translation guides specifically for weather terms are now prominently featured on the AMS' website. And that’s likely just the start of the Latinx committee’s initiatives as it hopes to improve Spanish language weather forecasts and grow the bilingual metorologists community.

Before we get into this any further, I’ve got to fess up on something here: I’m actually a part of the AMS Latinx Committee. Since the group formed earlier this year, I’ve served as a broadcast ambassador, where I help out with some of the initiatives you’ll read about below.

Just before I was born, my parents immigrated to the U.S. from Chile. I grew up speaking Spanish as my first language, and you’ll read a few anecdotes about all of that below.

Now that you know my background, I can also hopefully give you a bit of insight about why forecasting the weather in Spanish is harder than you’d think, because it’s kind of complicated.

First of all, Latin America is any landmass south of the U.S.-Mexico border on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. That means parts of the United States (Puerto Rico, notably) are part of Latin America, along with all of Central and South America and the Caribbean’s diverse array of islands.

That also means you’ve got a huge variety of languages, cultures and, yes, climates all bunched up over a relatively small amount of land.

Spanish dialects vary widely among Latin America. For example, Puerto Rico’s Spanish is often called “Spanglish” because of the outsized influence English plays in this unique version of Spanish.

Creole, Portuguese and other languages play big roles in shaping widely varying Spanish slang and dialects across Latin America, often making uniform communication a major challenge.

In addition to dialect-driven translation challenges, there are massive meteorological differences between Latin America and the U.S. You might not think about it on a daily basis, but most of the U.S. is arguably home to the world’s most diverse and extreme weather.

No country regularly experiences as many tornadoes or episodes of large hail – or even close – as the United States. We also see our fair share of hurricanes (especially in 2020), and depending on what part of the country you live in, crippling blizzards, wildfires, floods and/or earthquakes are common threats as well.

If Mother Nature has it in her arsenal, the U.S. probably experiences it. That’s not the case in Latin America, where severe weather and snow are rarely seen, hurricanes mainly impact the Caribbean and the weather, generally, is far calmer than the U.S. mainland.

Growing up in Chile, my parents experienced their fair share of huge earthquakes (my mom actually lived through the largest earthquake in recorded history), but they rarely, if ever, saw lightning, let alone a severe thunderstorm.

So living in the U.S., when a thunderstorm moved into view, my mom would panic, turn off all the lights in the house, and hide in an interior room. Of course, this would-be meteorologist didn’t exactly help matters by gleefully celebrating at the faintest rumble of thunder.

But, my mom’s anecdotal fear of thunderstorms is likely a result of her lack of experience with them growing up in arid central Chile, and Latin American immigrants can perhaps broadly apply that lesson.

Finally, there's the fact that weather terminology largely came about by and for English speakers. For example, if you directly translated the word "watch" on Google translate, as in a tornado watch, you'd instead get the word for a wristwatch (reloj).

The Spanish words for watches and warnings (as in a hurricane or tornado watch or warning) vary by country and meteorological situation, and that's mainly because direct translations for these crucial weather terms didn't exist or weren't widely agreed upon.

Until now.

Now that you know the many challenges translating and reaching Spanish-speaking audiences, you should also know that there are several initiatives underway to improve weather forecasts and outreach for those groups.

You’ve probably heard the saying “when thunder roars, go indoors.” The catchy, rhyming and free-flowing statement is easily remembered and applied, and there’s evidence it’s helped reduce lightning deaths.

In close coordination with the National Lightning Safety Council, the Latinx committee is now in the final stages of producing a similar saying for the Spanish-speaking community – an initiative that may take on extra importance now more than ever.

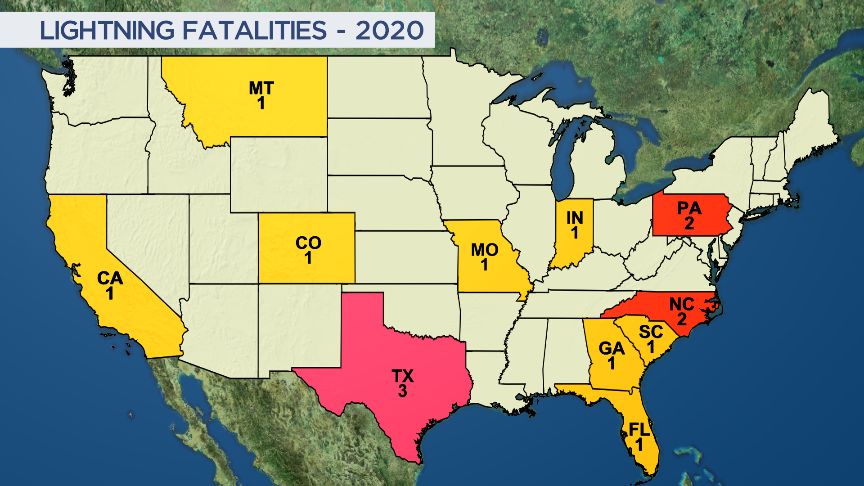

So far this year, Latin-derived last names account for six of the 15 lightning-related fatalities in the U.S. in 2020. That’s at least partly a result of the fact that Latinos, on average, have a significantly higher rate of outdoor professions than other population groups.

“The fact that ‘when thunder roars, go indoors!’ rhymes and gives you a direct action to take is something that has better familiarized the community with the threat of lightning,” Trujillo said. “And that’s something that’s been requested of us to do in Spanish.”

Of course, simply having proper translations for detailed weather terms like jet stream (corrente en chorro) or a tropical wave (ola tropical) was of especially high priority. While that’s now largely addressed with the aforementioned glossary, English-Spanish translations can now dive deeper into finding more effective ways of communicating potential weather threats to Spanish speakers.

“Whenever we go about translating from one language into another, what we have to make sure is that doesn’t happen is that words and terminology don’t get lost in the translation. There are so many dialects,” Trujillo said. “I am Peruvian, and I speak very, very differently than someone in Puerto Rico might. When it comes to risk terminology, and we use these terms more frequently, we have to be very careful and consider people’s world views and their dialects.”

Other initiatives are in the works as well, from mentorships for up-and-coming bilingual students to future translation services, all of which hope to increase weather awareness and improve forecasts for the Latin community.

“Through this collaboration, we hope to raise awareness and create resources for the (Latinx) community overall,” Trujillo said. "A lot of people don't have mentors, so this is also to make sure there's a space for us to collaborate and works things that help our community."