The House of Representatives on Thursday voted to pass a measure that combines two major voting rights bills — the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act — sending the measure to the Senate in a move that will likely set up a showdown over access to the ballot box.

H.R. 5746, also known as the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act, combines two major voting rights bills that have already passed the House of Representatives separately, but were impeded by Senate Republicans utilizing the filibuster last year.

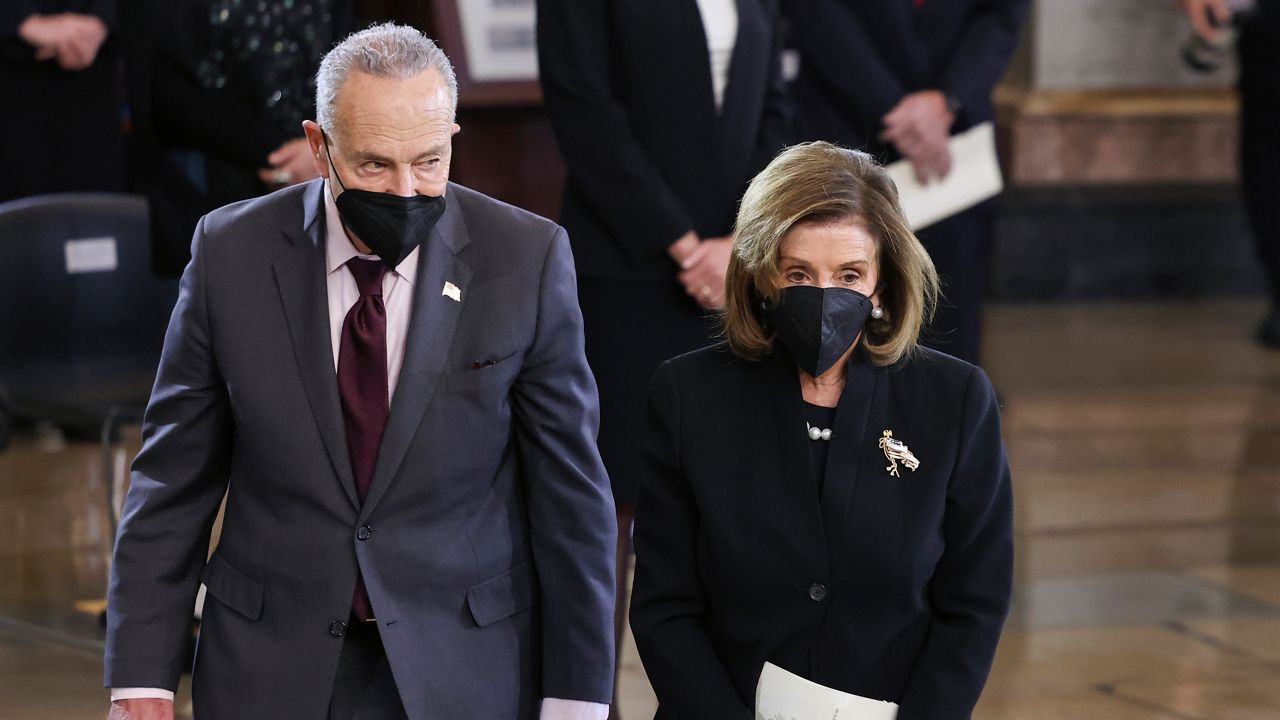

"By passing the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act, the Democratic House will make clear that we in this house stand with the president, yes, but with the American people to fight for voting rights," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., said on the House floor on Wednesday night in an impassioned speech. "Nothing less is at stake than our democracy. The sanctity of the vote. The integrity of our elections. That is what is at stake."

The sweeping Freedom to Vote Act, which carries the crucial backing of moderate Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, would make Election Day a national holiday, create a national standard for voter identification, crack down on long voting lines at polling places, expand mail-in voting and mandate states offer a minimum number of days for early voting. It would also outlaw partisan gerrymandering of resdistricting maps, overhaul campaign finance reform and make it a federal crime to harass or threaten election officials.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would update and restore provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was gutted by the Supreme Court in separate decisions in 2013 and 2021.

The House passed the combined bill Thursday in a 220-203 party line vote.

The vote took place hours before President Joe Biden was set to meet with the Senate Democratic caucus about their push to pass voting rights legislation and the possibility of changing Senate rules in order to do so.

"This is a defining moment that will divide everything before and everything after when the most fundamental American right that all others flow from, the right to vote and have your vote counted, is at risk," Psaki said Wednesday of the president's visit to Capitol Hill. "He's heading up to the Hill tomorrow to speak to the caucus and make the strong case that you've heard him make publicly directly to members."

Democrats are looking to take action to expand voting protections at the federal level after a number of states, largely with Republican-led statehouses, have enacted measures that restrict access to the ballot box. According to a tally from the Brennan Center for Justice, 19 states have passed 34 restrictive voting laws in the last year, the most since the group began tracking such legislation in 2011.

But getting voting rights passed in the evenly divided 50-50 Senate will be an uphill battle, especially with two moderate Democratic holdouts – Sens. Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona – opposed to changing the Senate's rules.

In a Senate floor speech on Thursday, Sinema appeared to pour cold water on Democrats' attempts to change Senate rules, saying that while she "strongly" supports "and will continue to vote for" the two voting bills, she does not support eliminating the 60-vote filibuster threshold.

"Eliminating the 60-vote threshold on a party line with the thinnest of possible majorities to pass these bills that I support will not guarantee that we prevent demagogues from winning office," Sinema said, calling it a "critical tool" to safeguard American democracy.

"While I continue to support these bills, I will not support separate actions that worsen the underlying disease of division affecting our country," she added. "There's no need for me to restate my longstanding support for the 60-vote threshold to pass legislation."

Sinema railed against restrictive voting laws in Republican-led states, saying they have "no place in a nation whose government is formed by free, fair, and open elections," and are "symptoms" of a divided nation, adding: "Threats to democracy are real."

The Arizona lawmaker said that she shares "the disappointment of many" that Republican leaders will not support election reform and stand up against restrictive voting measures, but added that "I wish there had been a more serious effort on the part of Democratic leaders to sit down with the other party and reforge common ground on these issues."

Sinema said that their "mandate" as an evenly divided Senate and thinly divided House is to work together to get things done, calling partisan division a "disease" that needs to be addressed: "We are divided. Our politics reflect and exacerbate these divisions."

In remarks following his meeting with a group of Senate Democrats on Thursday after Sinema's speech, the president was seemingly unsure of whether Congress would be able to pass through voting rights legislation this go-round without Sinema's support.

"I hope we can get this done," Biden told reporters on Capitol Hill. "The honest-to-God answer is I don't know [if] we're going to get this done."

"Like every other major civil rights bill that came along, if we missed the first time, we can come back and try it a second time. We missed this time," Biden continued, referring to a series of bills that passed in Republican-controlled states in recent months that limit various aspects of how individuals can vote.

The two moderate senators were set to visit the White House late Thursday night to meet with the president about voting rights, according to an administration official.

Biden on Tuesday made a vociferous push to change the Senate's filibuster rules, if necessary, to pass crucial voting rights legislation, which was met with condemnation from Republicans across the board. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., called his speech “profoundly unpresidential.”

“I have known, liked, and personally respected Joe Biden for many years, McConnell said on the Senate floor Wednesday. "I did not recognize the man at that podium yesterday."

It should be noted that McConnell is no stranger to changing the rules of the Senate: In 2017, Senate Republicans, led by McConnell as majority leader, invoked the “nuclear option” to confirm Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court with a simple majority vote, after refusing to take up the nomination of President Barack Obama’s pick Merrick Garland for 11 months. McConnell later called blocking Garland's nomination one of his "proudest moments" in a speech to supporters in Kentucky.

But McConnell was not the first to invoke the nuclear option in the Senate. In 2013, after Senate Republicans attempted to filibuster a number of President Obama’s nominees, then-Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., utilized the nuclear option to confirm most presidential appointments, but not Supreme Court nominees.