CLEVELAND — Public health officials in Cleveland are proposing updates to the city’s air pollution ordinances for the first time since 1977.

“For 50 years, they were doing all right, and they helped get us to the point where we are today,” Christina Yoka, the city of Cleveland’s chief of Air Pollution Outreach, said. “But now what we're seeing is that there's some more neighborhood level work and some neighborhood level air pollution that we're trying to address.”

The American Lung Association’s latest State of the Air Report ranks Cleveland as the ninth worst metro area in the country by “year round particle pollution.” According to the Cleveland Clinic, breathing in dirty air doesn’t just affect the lungs, it could increase risk of heart attack, stroke and more.

“It's really important to note, though, that even though we went to ninth for one of the pollutants, that was the first year that they included the wildfires,” Yoka said. “And because when we had the wildfires in 2023, that was just such very poor days for all of air quality, that was one of the big factors that led to us to being the ninth worst in the city.”

Regardless, she said, the division of air quality is working to improve health outcomes for Cleveland residents.

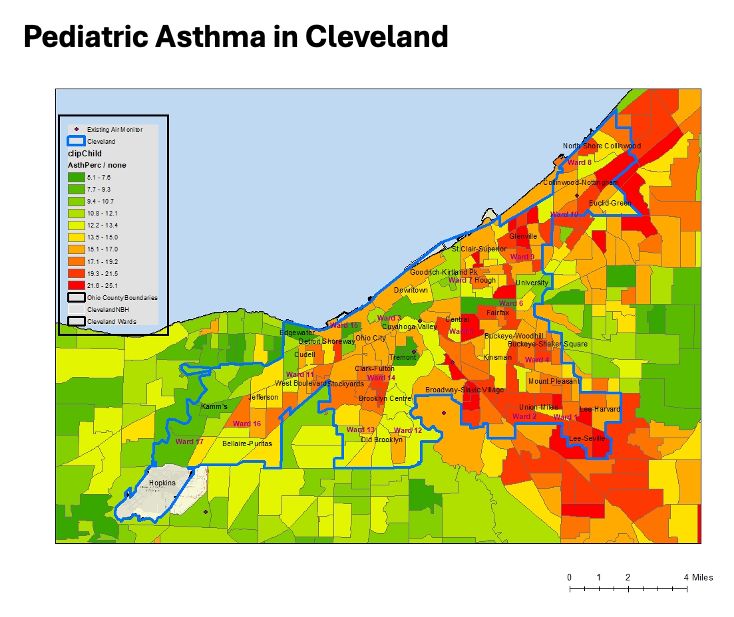

Data from the department of public health shows rates of childhood asthma differ greatly in different pockets of Cleveland. In some neighborhoods, like Slavic Village, nearly one in four kids suffers from asthma, but drive 10 minutes northwest to Tremont, and the childhood asthma rate drops to 5 to 7%.

“We are far exceeding the national average for asthma,” Yoka said. “But that is not felt evenly across all of the city of Cleveland. The residents that are experiencing that, typically, are in areas like the industrial valley. They're on the east side.”

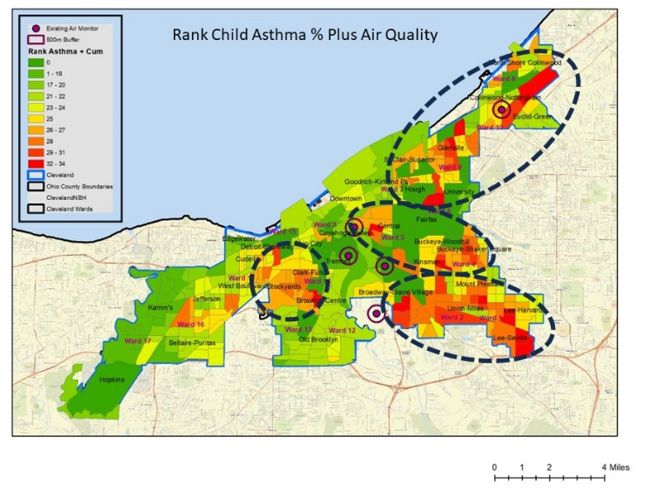

Yoka said her team is working with residents in problem neighborhoods to identify why these health disparities are taking place while they propose increasing regulations.

“We're taking the approach of something called cumulative impacts,” she said. “So this is where you look at all of the industry. You look at all the environmental factors. You look at vulnerable data, so that could be population. It could be age. It could be a multitude of factors, and you see, for residents are living in certain city neighborhoods, how do all of those factors come together and impact their health?”

The proposed updates to Cleveland’s air pollution code would impose stricter regulations on industries with facilities in the neighborhoods facing the poorest health outcomes. If those facilities exceed a certain level of pollution, they’ll face further permitting requirements. Yoka said that could mean requiring businesses to complete a work practice plan that outlines how they intend to address specific concerns.

“Under certain cases, they might have to do a full-on health impact assessment,” she said. “A health impact assessment requires them to go out into the community, get community feedback, and develop a risk analysis. Who's at risk? And, what impact could this have on the community? And then that report also needs to include how did they address community concerns in their new proposal.”

The proposal also includes new provisions to crack down on vehicle idling and open burning, establish an indoor air quality program and require all city departments to develop action plans for when air quality levels pass a certain threshold.

Anette Irby, a Cleveland resident in a high-risk neighborhood, said her house is near a highway with traffic that kicks up dust and a steel yard.

“You can smell that smell like gas burning and stuff like that. So, that’s made me kind of concerned,” Irby said.

She said she and her grandson who lives nearby both have asthma. While Irby plans to move soon, she’s glad to learn public health officials are working to create cleaner air because she doesn’t want more kids to suffer like her grandson has.

“It’s just not right,” Irby said. “I hate to see any kid go to stuff like that.”

Yoka said she knows the new standards will be difficult for industry and businesses to adjust to, if they pass. But, she’s hopeful they can work together to improve outcomes for everyone.

“The health of the residents impacts the health of the industry,” Yoka said. “If residents are sick, that means they're not coming to work. If residents are sick, that means they're not purchasing your products. So when industry and community work together, that means that the industry can continue to produce the important things that they do.”

The proposed new air code was introduced to Cleveland City Council in March. It is expected to go to committee this month before council votes on whether to approve it.