Out on the tarmac of Republic Airport on Long Island, Kamora Freeland meticulously checks the wings, wheels and propeller of a Piper Archer 180. Then she steps on the wing, pops the door, and climbs into the cockpit.

Freeland is a pro now, but just three years ago she was piloting her first flight. She recalls the experience in vivid detail.

“It was just, like amazing seeing the growth in that view. You know, seeing the ocean, the city from the distance. So just like, oh, I was like, I could do this for a living,” Freeland remembers.

It’s a goal the 18-year-old Staten Islander has her sights on …. but she is setting records along the way. Freeland became the youngest licensed Black pilot in New York state last year and one of the youngest in the country.

“That I could make history and like, maybe my name would be in the same textbooks as Bessie Coleman, or even the Tuskegee Airmen, because they paved the way for me. So, it was just knowing that I could possibly have some sort of impact like they had on me,” she said.

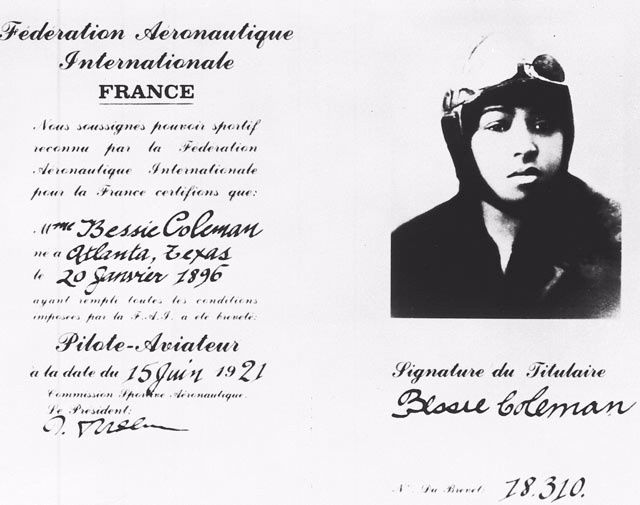

Bessie Coleman was the first African American woman to hold a pilot’s license. Coleman was born in Atlanta Texas in 1892 and was one of 13 children. Her pilot dreams took flight during a conversation with her brothers.

“[Her brothers] were World War One veterans, and they recalled seeing black women pilots flying in France,” explained Dorothy Cochrane, an aviation curator at the National Air and Space Museum. “And she took that, and she was startled by that and just said, ‘Wow, you know, that's it. I would like to do that.’”

But there were several obstacles in her path.

“Because she was African American. Because she was a woman. She really had two strikes against her, and they were huge strikes as far as realizing her dream to become a pilot,” said Cochrane.

Cochrane explained how newspaper publisher Robert Abbott put Coleman on the right course.

“He said, you know, you heard about these women in France. You need to go to France.”

)

After receiving her license in 1921 and taking additional training, Coleman started barnstorming. It was a popular style of flying in the roaring 20’s involving ariel stunts like loops, rolls and wing-walking – some viewed it as a flying circus.

“They just got the idea of going from town to town, farm to farm, field to field, putting on air shows, and that's how they earned a living,” Cochrane said.

In 1922, Coleman made her first appearance in New York where the show billed her as the "the world's greatest woman flier." For a short 5 years she was headlining shows and dazzling audiences even earning the nickname Queen Bess – and fighting segregation and racism along the way.

“Her shows were open to everyone,” Cochrane said. “She did not want to perform just for black Americans. She wanted to fly for all Americans.”

But then in 1926 her life was suddenly cut short. During a test flight before a show, Coleman was leaning over the edge to survey the ground when the plane went out of control. Coleman, who was not wearing her seatbelt at the time, fell to her death.

“It was so disheartening for everybody because she was really coming into her own. They looked like there was a future there,” said Cochrane.

But her dedication laid the groundwork for the future. A future that includes women like Freeland.

“She went through a lot of challenges, you know, facing racism. But she was able to do it. So that lets me know, all the circumstances that she was under, if she can do it, I can do it,” said Freeland.

Before she died Coleman dreamed of opening a flight school that didn’t have restrictions based on gender or race. Freeland also dreams of opening a school to inspire the next generation.

“Representation matters,” she said. “And when you don't see people in the fields, you don't know that you can do it too. So, I just want to show them that young black girls or young black kids can do it too.”

This summer, Freeland hopes to complete her instrument training, which will allow her to fly in zero-visibility conditions. From there, not even the sky is the limit.