Political conventions are a time-honored tradition that date to the 19th century, but they're not legally required by federal or state law, and there's nothing in the Constitution that says they're required to nominate a presidential candidate.

It turns out there are few official, overarching rules for conventions. Each party establishes its own rules for nominating its candidate. Every presidential election cycle, both parties put out an official call announcing the date and site. There's no specific, set date for this call.

Decision 2016: Full Convention Coverage

The central purpose of the conventions is to nominate the Democrat and Republican parties’ presidential and vice presidential candidates.

U.S. delegates and representatives from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. territories of Guam, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, the Northern Marianas and Puerto Rico will descend upon Cleveland and Philadelphia this summer for the two conventions:

- The Republican National Convention will be at the Quicken Loans Arena July 18-21 in Cleveland, Ohio.

- The Democratic National Convention will be at the Wells Fargo Center July 25-28 in Philadelphia.

Every U.S. state and territory is given a certain number of voting representatives, or delegates, and the size of each delegation is determined by factors such as population, proportion of that state’s Congressional representatives or state officials who are party members and the state’s presidential voting patterns.

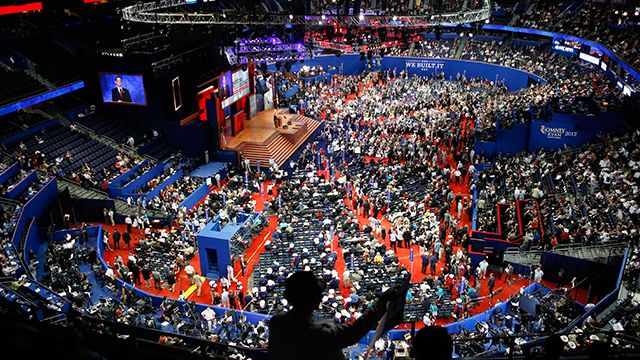

The conventions, really, look more like big, noisy parties with balloons. That’s because by the time the conventions roll around, it’s likely already known who is the party’s candidate, because of already-held state primary elections and caucuses. Due to the scheduling of caucuses and primary elections early in the election year, the party's presidential nominee is usually known months before the conventions.

What if the candidate is not clear? Since the 1970s, the major party nominees for the presidency rarely have been in doubt, so convention voting is perfunctory, usually requiring only a single ballot (a roll call vote of the states’ delegates). The primary election season leading up to a convention usually identifies a clear nominee or front-runner. If no single candidate emerges by the end of the primary season, however, a scenario called a brokered convention could result. In a brokered convention, a presidential nominee would be selected at the convention through a series of ballots and bargaining between leading candidates and lesser candidates or party leaders for their delegates.

The other two purposes of the convention are to adopt the party's platform and principles, and rules for the next election cycle, including the procedure for selecting the presidential candidate for years later.

Conventions serve a very important cultural function too. They're the springboard, so to speak, for the final months of the electoral push. The party comes together to rally behind its chosen candidates, and voters who may not have been paying attention to the election suddenly take notice of the candidates. The convention provides a symbolic moment of pride and enthusiasm, and an opportunity to show party strength.

Who attends the convention?

By casting ballots for one candidate or another during the primary season, voters are actually selecting delegates to the party conventions. Conventions are not open to the public. The public watches through the eyes of 15,000 broadcast and print journalists. In addition to delegates and the press, events of this magnitude require an army of volunteers. More than 40,000 people may actually be inside the two conventions, while any demonstrators who turn up will march and rally outside to promote their causes.

What happens at the convention?

Party conventions usually last four days. During the day, committees meet to certify delegates, deliver reports and determine the party's platform. During prime-time viewing, the convention becomes a media event. There is a keynote speech by a prominent party leader, and the alphabetical roll call vote on the third night, when each state gets a moment in the spotlight. With the nominee already selected, the only suspense is which state will put the nominee over the top? On the fourth and final night, delegates affirm the vice presidential nominee, and the party's nominee makes an acceptance speech. Then, if past practice is any indication, 100,000 balloons will drop from the ceiling, signifying that the party is over but the general election season has begun.

Who pays for it?

Private contributions, state and local government assistance and federal funds pay the bills. The local economy benefits as convention attendees eat at restaurants, book hotel rooms and enjoy what entertainment the host city has to offer.

Who benefits from a convention?

The host city may get an economic boost, but the main benefactor is the party's presidential nominee. National political conventions often provide a "bounce," or temporary uptick, in their nominee's poll numbers. Richard Nixon, George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton trailed in the polls until their conventions and then grabbed the lead after they were officially nominated. Since 1936, the party not occupying the White House has held its convention first. That often provides a bounce in poll numbers that lasts until the incumbent party holds its convention, which may then receive a bounce of its own.