HAMERSVILLE, Ohio — Terry Ogden says he was the second dumbest student from his 1966 graduating class, and that his high school sweetheart was clearly the dumbest.

What You Need To Know

- A Brown Co. man is in need of a kidney

- He has placed signs throughout rural yards and roadways

- He hopes someone’s generosity with help him

- Nearly 100,000 are on the waitlist for a kidney

"She was the salutatorian of our class when we graduated. She was the second smartest and I said, 'I was always the second dumbest in the class' and I always said, 'I wonder who was dumber than me? Well, it had to be her because she ended up marrying me,’” joked Ogden, who turned 72 years old in August.

"Yep, the smart homecoming queen, that's right... as dumb as I am.”

His now-wife, Elaine, still brings that to his attention from time to time during the 53 years they have been married, he said laughing, just as his phone alarm sounds.

It is reminding him to take his pills — just one small part of his daily regime these days.

Last year, sitting inside his doctor’s office next to his wife and daughter, he was told that his kidneys were collectively functioning at 10 percent.

"That's when everybody got scared,” Terry remembered. "It's a big shock to know that I've gone from perfect health to you don't how many more days you've got to go.”

He was placed on the kidney donor wait list. But that could take years.

"I can't wait three to five years," he said.

So, he decided to advertise his request to his neighbors.

"I told my wife, 'it’s not doing any good not telling anybody.’"

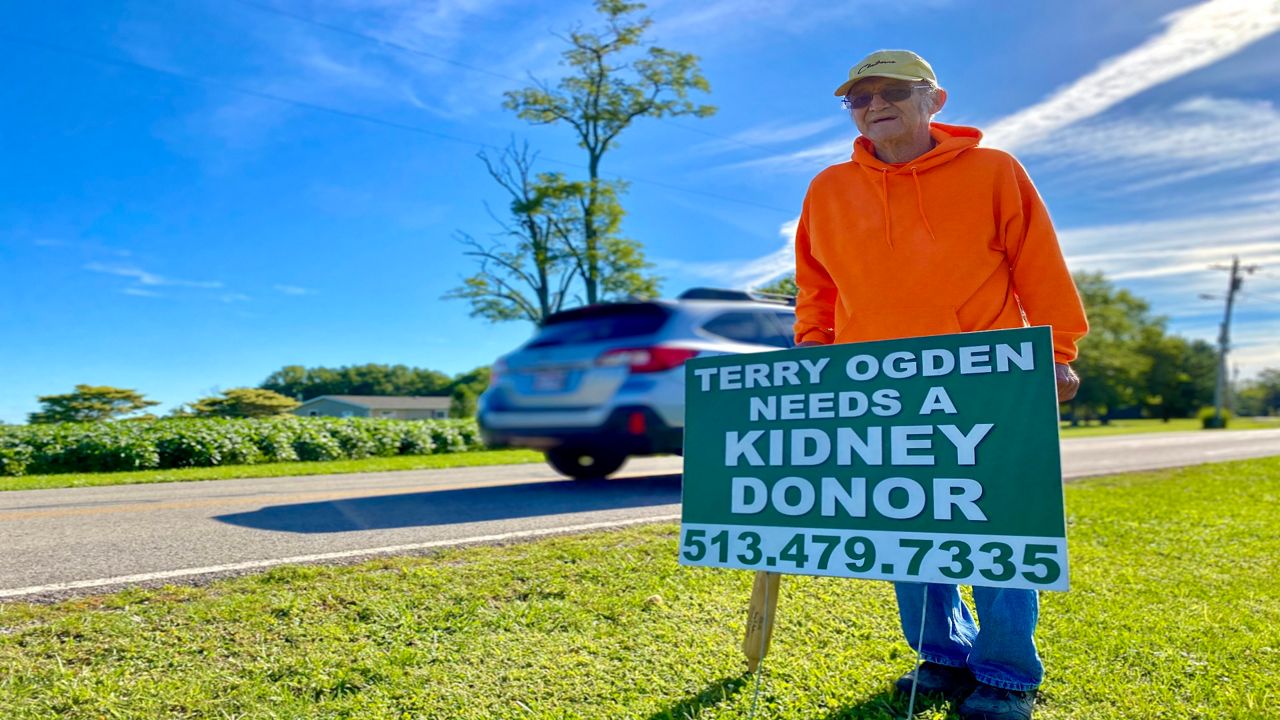

So, starting in his own yard, he put up a sign just at the edge of the two-lane country road about a mile from the Hamersville’s tiny downtown and across the street from two large silver silos and a soybean field.

The green yard sign reads in all capitalized white letters: “TERRY OGDEN NEEDS A KIDNEY DONOR” with his phone number at the bottom.

But since Hamersville has a population of only 500, he sought out yards throughout the county and beyond to advertise for a kidney donor.

About a month ago, he plunged the metal stakes of 14 yard signs down into the grass in friends’ yards and businesses spanning across Brown County and neighboring Clermont County.

Amid hand-written roadside signs for fresh tomatoes and homegrown sweet corn, signs can be spotted in Williamsburg, Bethel, Hamersville, Mt. Orab, Georgetown, and Sardinia.

He takes time each week, he said, to visit each sign and trim the grass and weeds that may have grown around them to make sure they are visible to passersby. One of his signs is affixed to BJ’s Lake and Restaurant’s pole on Ohio 125 between Bethel and Hamersville.

BJ’s Lake and Restaurant, a roadside fishing spot and mom-n-pop diner displays Terry’s sign just under a faded Mountain Dew sign and their own marquee indicating that they are open from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., for breakfast and lunch.

With a coffee in her hand, BJ’s owner, Barb Donell, stands down the hill at the lake behind the restaurant, talking to some friends who are sitting on a bench with their fishing poles in the water.

Wearing a royal-blue T-shirt, the 69-year-old makes her way up the grassy knoll. Her jet-black hair is tied up in a bun and tucked neatly into a hairnet underneath a navy-blue visor with a “BJ’s Lake & Restaurant” logo embroidered on it.

Walking back up to the restaurant, which was built in 1951, Barb said that she and her husband Frank bought the local favorite in 1983. And it continues to be a family affair, with her grandson manning the lake and her daughter working in the restaurant.

It’s just after 10 a.m. on a Thursday morning, and inside the eatery, it is jam-packed with locals getting their fill of home-cooked omelets and fresh-baked pies. The community loves them, she said, and she reciprocates those sentiments.

"We've been in the community for 37 years and I would do anything to help anybody.”

Barb said she has always had a soft spot for the community and its people. They have been there for each other over the decades.

"They've all supported us over the years. They've been very good to us and during this pandemic and stuff; they have really just outdone themselves – supporting local businesses,” Barb said.

Just like most small towns, everyone knows everyone, and that is how Terry’s sign made it to the lake’s property.

Terry went to school with Frank and played basketball with him at Hamersville High School.

However, Frank died a few years back while waiting on a liver transplant list. So, Barb understands the pain and uncertainty of waiting for an organ donor.

"I hope that somebody goes by and he gets a kidney, I do, because my husband was on list for a liver transplant but he didn't get it,” Barb said. “So, I'm hoping the best for Terry. That's why I didn't hesitate at all for him to put that sign up out there.”

A rustic cuckoo clock in Terry's living room chimes, indicating a new hour.

He reminisces about high school, when he met Elaine.

"I've always been Hamersville; everything's always been green and gold," said the lifelong Brown County resident, who was born on a 150-acre dairy, corn and soybean farm in Locust Ridge.

While Elaine was not allowed to date when they started talking, Terry said, they hung out at school and at events like his varsity basketball games.

"[She] sat there and routed on me to sit on the bench and not fall off the bench," he joked.

Their senior year, Elaine was crowned the basketball homecoming queen and they attended the dance after the game together with his friend and his date. Terry quickly admitting that even though he did not know how to dance, with the exception of a little slow dancing, they "had a great time. It was a great night.”

Terry is a little foggy about some memories, he does not hesitate when touting the day he became a husband.

A year after they graduated, on Nov. 24 1967, the 19-year-old married his high school sweetheart, after proposing to her in the house they still live in today – where Elaine’s mother lived at the time.

He points to a closed bedroom door that used to be the living room, as the place where he popped the question to her and her mother. He asked her mother what she thought – and while she thought they were too young, she gave her blessing. And Elaine said, “yes.”

"I knew she'd say yes, there were no two ways about it," he chuckled.

And she has remained by his side ever since.

"We're together all the time. We do everything together,” Terry said.

These days, it is his sweetheart who sets up his dialysis machine each night for him before she goes to bed.

Every night since March, Terry lays on his couch in the living room for nine hours as the solution pumps into his stomach, flushing out his system until 5 a.m., when it is time to get up and get ready for work again, he said lifting up his hunter-orange hoodie, revealing his dialysis port in his stomach.

"I have just enough time to get home, go take a quick shower, come out here, get hooked up to the machine. Then, I eat my supper," he said following a 12-hour shift as a fork truck driver at Mauser in Newtown – about a 45-minute commute three to four days a week.

In fact, he just celebrated 50 years with his company in March and has no plans to retire any time soon.

Terry said that he was in “perfect health” until 2017 following a hernia surgery, which had been plaguing him for nearly five years prior.

"Ever since I had that operation, my health has just gone downhill.... everything went to pot since then.”

Since beginning dialysis treatments, he has had to have a hole in his large intestine repaired and has undergone a second hernia surgery.

His doctors told him his health would be even worse had he not been so active in sports year round for the majority of his life.

"My exercise has always been when I'm out there officiating,” said Terry, who, along with Elaine, coached, refereed and umpired for baseball, basketball, volleyball, softball for 44 years, before retiring because of his health.

The self-proclaimed “sports nut” said his passion for sports started while he was in school – and that is where his love for Elaine was also cemented.

At the beginning of their senior year, they were both in a play together. He was the undertaker with two lines and she had the lead role.

Although he does not recall what the play was, he does remember a moment after school during rehearsal that he shared with his sweetheart.

One day after school, he had a dental appointment to have a tooth pulled before he could attend play rehearsal. When he returned to school for rehearsal, she reached over and patted his swollen jaw and made a loving jab at him, "Oh, I feel sorry for your little tooth.”

They both laughed through his pain, and that is when he knew, she was the one.

"And from that point on, it was love ever after... that started it all," he smiled.

Growing up on a Brown County farm, it is no surprise that one of his favorite times of the year is the end of September, when the county fair rolls around.

As the fair gets underway each year, political signs litter yards throughout the village of Georgetown. And that is what he is saving his 15th donor sign for, hoping to catch the right person’s eyes with all of the fair’s foot traffic through town.

"I'm saving it for the fair. When the fair comes around, I'm going to put one up there by entrance,” he said.

Each year, he said, he and Elaine used to take off work the week of the Brown County Fair – known as the Little State Fair – and partake in his must-do list: watch horse shows and eat gobs of county-raised pork tenderloin sandwiches.

"We would open it up every morning and close it down every night,” he said.

But not this year.

"I have to watch what I do out in public with the health issues,” he said about his kidney, along with the looming COVID-19 pandemic.

Even though the fair is off his to-do list this year, one thing he can still do is go outside and enjoy his “babies.”

Wearing baggy stonewashed jeans, black gym shoes and a tan baseball cap, he walks across his wooden porch filled with metal trinkets and spinning pinwheels, amid a handful of goat statues and a row of welcome signs.

Using the handrail, he walks slowly down the steps to the gravel.

Making his way down the driveway to the barn out back, the rocks crackle under his feet as he walks carefully with a cane that he proudly fashioned out a Louisville slugger baseball bat.

His silver-framed spectacles darken when the sun hits them, while he peers out into the field where four of his six goats refuse to eat the grass.

"They have plenty of grass to eat out there, they won't eat grass. They eat the bark off the trees," Terry said laughing.

Tuffs of his white hair protrude from underneath his hat and over his ears, as he stands in the overgrown grass, talking to his goats.

Standing in a cluster around him, they wag their tails and stare intently with curiosity.

Each morning before he would leave for work, he used to feed the goats grain, since they refuse to eat grass, or even hay, he said.

However, these days, Elaine takes care of them, until he is feeling healthier.

Looking over his shoulder at his babies, he walks back over to the gate and closes it behind him, locking it with a thick, clunky metal chain.

Aside from a wife who has taken over his goat-feeding duties and setting up his dialysis nightly, Terry said the secret to a long, blissful marriage is: “Trust. [And] we don't argue... every once in a while, not very much. Probably two or three arguments since we've been married, nothing serious.”

He hopes a kidney donor will allow him to have many more years with Elaine by his side.

"I'm just hoping that somebody has a feeling and wants to donate. I just want to see somebody want to help. I'm hoping I've got friends out there," he said, quickly quipping, "you know, they always say you don't have friends when you're a sports official, only enemies there... but I'm just hoping somebody will open their eyes and be generous enough.”

For him, recovery time for a new kidney would take three to four months, he said. However, for the donor, it is about a month to recover.

Today, he said, he feels good, except for a shortness of breath due to fibrosis.

In addition to the opportunity to grow old with his high school sweetheart, Terry said if he gets a new kidney, he might finally consider retiring from his job and he would like to be able to take care of his goats again.

“I just want to live my life normal,” Terry said.

If you are interested in finding out if you might be a kidney donor match for Terry, give him a ring at (513) 479-7335.

There are nearly 100,000 people waiting for a kidney transplant like Terry, according to the American Kidney Fund.

For more information about living kidney donors and how you can find out if you are a viable candidate, visit https://www.uchealth.com/en/treatments/kidney-transplant.