In our country’s nearly 250-year history there have been forty-six presidents, all of whom were men. If Kamala Harris wins this election, it would be a historic achievement, but one that was centuries in the making. Our Bree Driscoll breaks down the historical significance of both candidates in our two-part series “If She Wins or If He wins.” Today we look at how Vice President Kamala Harris is one of the many women who aimed to break the glass ceiling.

What You Need To Know

- Women have been running for President for more than a century

- How will gender shape the presidential election?

- Former President Trump would be only the second President to win a second term after losing his first bid for reelection

In August, Vice President Kamala Harris took the stage at the Democratic National Convention to accept the party’s nomination for president. She was only the second woman ever to achieve that milestone, and the first woman of color.

“The presidency sets a standard, an expectation,” said Kelly Dittmar, the director of research at Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics.

“You’re putting yourself out there as a woman who can and should lead in top executive office. You’re challenging voters to think a little bit differently about what’s possible.”

Even more historic is the possibility of a Harris victory. If she wins the election in November, she will become the first woman to hold the nation’s highest office.

“If you think about what most individuals, most citizens in this country know about politics, they know who the president is,” said Dittmar.

“They’re typically going to think of a picture of the president. And that picture, for so much of U.S. history, has been white and male.”

It’s the highest glass ceiling in American politics, and one that women have been trying to break for generations—each candidate making small strides toward that goal.

“I think every woman who’s run for office, but especially presidential office, has really chipped away again at these expectations,” Dittmar explained.

Rachelle Suissa has dedicated her life to this type of progress. She believes both parties would benefit from having more women on the ballot at every level of government.

“Women bring, number one, their life experience, right? Which inevitably invariably has to be different than that of men’s,” Suissa said.

Suissa’s nonprofit organization, Dare to Run, encourages women to run for office through mentorship programs and classes.

“The first semester focuses on how to run a successful campaign,” she explained. “The second semester focuses on what to do once you’ve been elected to public office.”

While her organization is non-partisan, Suissa herself has been a supporter of Harris since 2019 primary campaign and says she’s excited to vote for her in November.

“I love that she’s a woman, but obviously that can’t be the only thing you vote on, right?” Suissa said. “I like what she stands for, and I like how outspoken she is about women’s rights and women’s issues.”

She also recognizes what it took to get this point.

“One hundred years ago, you wouldn’t see this many people at the DNC convention for Belva Lockwood,” she observed. “It just wouldn’t happen, right?”

Belva Ann Lockwood, who ran in 1884, and Victoria Woodhull, who ran a decade earlier, pioneered seeking elected office for women, and had deep ties to the women’s rights movement. Their campaigns challenged societal norms when women didn’t even have the right to vote.

“These early candidacies are really overlapping as well with the suffrage movement and the fight for women to be more involved in politics in a formal way,” explained Dittmar.

Despite the momentum, progress was slow. It would take nearly half a century until women secured the right to vote, and almost 80 years before a woman ran again for President.

In the 1960s and 70s, a growing push for gender equality led to an increase in women running for office at all levels.

“Margaret Chase Smith is one of those women,” said Dittmar.

Chase Smith, a Republican Senator from Maine, had served over 20 years in Congress before deciding to run for president in 1964, becoming the first woman to have her name in nomination for a major party.

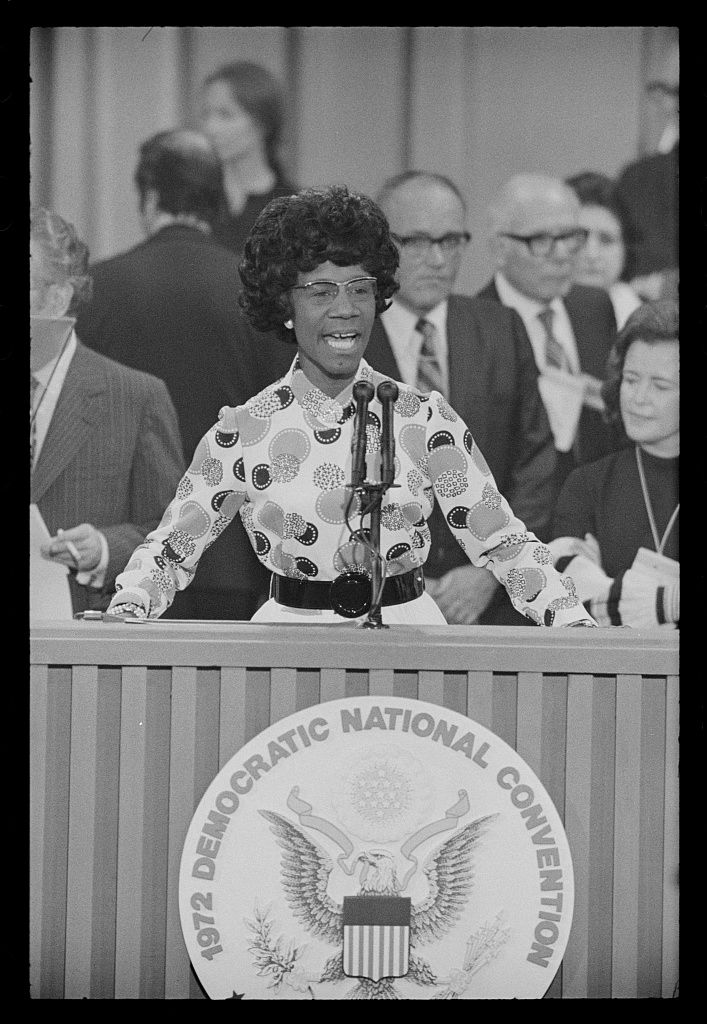

In 1972, Shirley Chisholm achieved the same in the Democratic party, earning the distinction of being the first Black woman to run on a major party ticket.

“She really wanted to be taken seriously,” said Dittmar.

Throughout her campaign, Chisholm fought to be included in important aspects of the political process, like debates and other media coverage.

Despite some inroads, including vice presidential nominations on major party tickets, it would be over 40 years before a woman claimed a major party nomination for the highest office in the land.

In her second presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton finally cleared that hurdle—with a campaign that highlighted the historic achievement.

“She would say, you know, I’m not asking to vote for you to vote for me because I’m a woman and I want you to vote for me on the merits. But one of those merits is that I’m a woman. One of those merits is that we’ve never had a woman in the oval office, and I bring lived experience and perspectives that haven’t been in these conversations before,” Dittmar said.

On election night, the stage was set for her victory—set up beneath a literal glass ceiling at New York City’s Javits Center. But the ceiling remained intact after she lost the race to former president Donald Trump.

“There was a real question after 2016 if Clinton’s loss would make women not want to run,” noted Dittmar.

But future races proved otherwise, with an explosion of highly qualified female candidates, including Kamala Harris, who became the country’s first female Vice President in 2020.

That achievement helped to pave the way for her own campaign four years later.

If she wins, it would be a major milestone for women in politics.

“Does that then inspire more women to run?“ wondered Dittmar. “We hope so.”

A Harris victory could also usher in a change that is more than just symbolic.

“We can’t even expect the ways in which her lived experience and perspective might change the conversation, change the voices she brings into the room, and ultimately change some outcomes in terms of the future of the country,” Dittmar said.

Those changes could potentially inspire the next generation of women leaders along the way.

“I think people want change. They want to see somebody that looks like them and thinks like them and acts like them running for office,” Said Suissa. “And I think a lot of people see that, maybe not everybody, but a lot of people see that in Kamala Harris.”