Lawmakers took a hard look Wednesday at proposed legislation to reform New York state's parole system and make it easier for incarcerated people to get a chance at release.

The Senate Crime Victims, Crime and Correction and Judiciary committees held a hearing in the Legislative Office Building to examine opinions about the Fair & Timely Parole and Elder Parole bills, which would reduce the number of elderly people in prison and long sentences.

The Fair and Timely Parole bill would allow the parole board to release a person from prison based on behavior and merit.

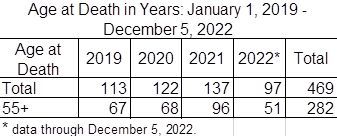

Elder Parole would make anyone over the age of 55 who has served 15 years in prison eligible for a parole hearing. The state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision classes an incarcerated person as "older" when they turn 55. A person's life expectancy declines about two years each year they spend in prison.

"We teach individuals to be optimistic about life and we preach that the worst thing does not define you, but when you get before the parole board, there and moving forward, we are always looked at in that one measure of time on who we are — as if we're not dynamic, but stagnant," said Anthony Dixon, Parole Preparation Project director of community engagement.

Dixon spent more than 25 years in maximum-security prisons across New York and was denied parole multiple times before his release.

He says the state doesn't prepare people for parole hearings, which on average are about a 15-minute video conference, especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

He urged lawmakers to not just visit the facilities, but tour the cemeteries of New Yorkers who died behind bars — a majority who are Black or person of color.

"This is a real life-and-death issue in New York state prisons," Dixon said. "They are not only terrified of the parole board, they are terrified because they think if nothing is done, they will die."

Incarcerated New Yorkers can prepare for their interviews with the Parole Board with guidance from the facility's Offender Rehabilitation Coordinator or Supervising Offender Rehabilitation Coordinator, according to the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS).

"All incarcerated individuals, within six months from their parole interview, are provided the opportunity to participate in a Parole Board Preparation Workshop," department spokesman Thomas Mailey said in a statement Wednesday. "This includes preparation of written materials, discussion, mock interviews and a DVD which includes down-to-earth and reassuring explanations from two different Parole Board commissioners, as well as presentations from formerly incarcerated individuals and their prior experiences in appearing before the board. They should be prepared to discuss their involvement in the instant offense and to answer questions about their prior criminal activity, custodial record, program participation, future goals and release plans."

Incarcerated people meet with their assigned offender rehabilitation coordinator four months before their interview, Mailey said.

But multiple formerly incarcerated people who spoke at the hearing testified they did not receive guidance or assistance to prepare for their interview.

The state reports 31,338 incarcerated New Yorkers as of Wednesday, a 57% decline from the department's peak of 72,649 people in prison in 1999, according to DOCCS.

About 40% of New York's prison population are eligible for parole, advocates said.

With elections over, bill sponsor Sen. Julia Salazar, who chairs the Crime Victims, Crime & Correction Committee, is hopeful the proposed changes in Fair & Timely and Elder Parole will advance next session.

"So much of the misunderstanding that I've seen about the bills is actually rooted in a lack of understanding of the parole system, and understanding that just because someone goes to the parole board does not mean that they are definitely going to be released," said Salazar, a Democrat representing parts of Brooklyn and Queens. "The majority of people who go before the parole board for the first time are not granted parole."

The commissioners of the state Department of Correction & Community Supervision and the state parole board were both invited to testify, but declined. State officials often do not comment on pending legislation.

If they become law, the bills would change the criteria parole board members must use to decide if a person is released.

That upsets Republican lawmakers who say the board must equally consider impact on victims and their families.

They're also against how every incarcerated person would have an opportunity for a release hearing, including those sentenced to life without parole.

"We cannot address these issues with broad strokes like this," Sen. Anthony Palumbo, a Republican from New Suffolk. "That's really my concern, that do some fixes need to be made? Yes. But I'm concerned this is a one-sided perspective."

Republicans have not proposed specific changes to either measure. But Sen. Jim Tedisco, a Republican from Glenville, introduced a bill last session in memory of two high school seniors who were killed by a drunken driver in 2012 that would require parole board members watch recorded statements from victims before voting to release a criminal offender.

Several victims of violent crimes and their families testified Wednesday in favor of both measures, saying the people who harmed them must have an opportunity to re-enter society to change the racist cycle of people who endure interpersonal violence and end up imprisoned.

Alexandra Bailey, an end life imprisonment strategist with The Sentencing Project, is a survivor of rape and childhood sexual abuse.

"Are you going to spend your money turning our facilities into hospice and elder homes?" she asked lawmakers during testimony. "Or are you going to allow people the dignity of the second chance that as we can see they 100% have earned and deserve?"

Releasing aging people from prison is estimated to save the state up to $189 million per year, according to data from Salazar's office. It costs the state about $60,000 to incarcerate one person per year, but between $100,000 and $240,000 to house an elderly person in prison annually.

It's a discussion about state resources for successful rehabilitation that will continue when lawmakers return to Albany on Jan. 4.

"This upcoming session, we'll essentially have a new Legislature — many of whom have already expressed support for parole justice and both of these bills," Salazar said. "This is a new year, a new opportunity to look at this legislation with fresh eyes."