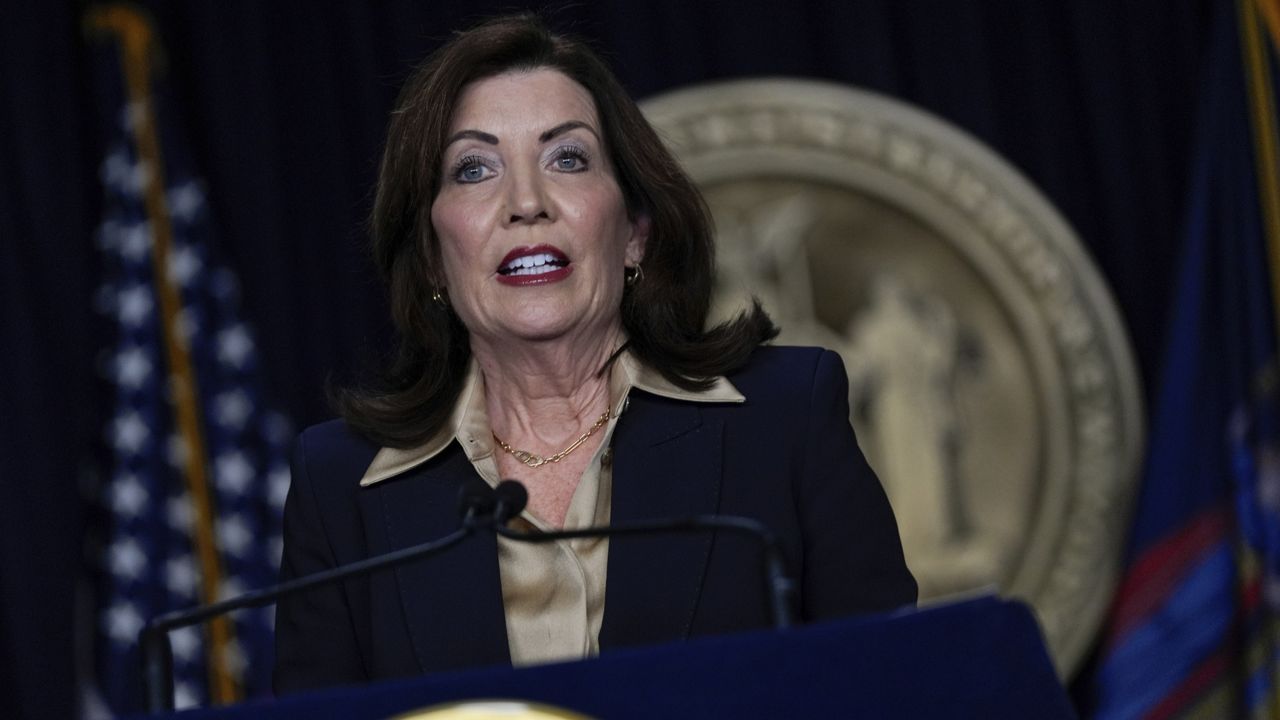

Gov. Kathy Hochul promised to fully staff the state Parole Board during her State of the State address in January, but the board continues to have the same number of members six months later.

The board has had 15 of 19 members for the past several years, and before the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

The governor appoints parole commissioners who must be confirmed by the state Senate for six-year terms. Senators confirmed Darryl Towns to the Parole Board on June 6, but member Erik Berliner's term expired June 18, returning to four vacancies and leaving things where they started.

"Frankly, I think a fully staffed parole board, I don't even know what that looks like because I didn't experience it, would make a big difference in morale with parole board members, but also more efficient for people coming before the board," said former Parole Board Commissioner Carol Shapiro.

Shapiro served as a commissioner on the board from 2017-2019, and there were several vacancies then, she said.

"The Board of Parole continues to conduct interviews and issue determinations, and decisions continue to be issued within two weeks of the interview date," said state Department of Correction and Community Supervision spokeswoman Rachel Connors, citing state Executive Law.

Hochul promised to fully staff the parole board as part of her Jails to Jobs initiative announced in her executive budget in January.

Hochul and the Legislature agreed to allocate $7.5 million to fully staff the board in the latest $220 billion state budget, including commissioners' salaries, benefits and administrative costs. Parole Board commissioners make $140,000 each year.

"We are actively reviewing candidates to be nominated to fill the four additional seats on the Parole Board — increasing the board’s capacity to hear cases,” said Jim Urso, Hochul's deputy director of communications.

Passing the Clean Slate Act was also part of Hochul's Jails to Jobs initiative, which also failed to pass this session.

"After making public safety a key part of her 2022 State of the State Agenda, Gov. Hochul successfully restored the Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) for incarcerated individuals and will continue to work with the Legislature on the Clean Slate Act and other much-needed efforts that will keep New Yorkers safe while righting the wrongs of an unjust criminal justice system,” Urso said.

Parole board hearings have sharply declined since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 with 6,280 hearings held in 2021, compared to 10,072 hearings held in 2019, or a decrease of almost 38%, according to DOCCS. The department attributes the decline to the 13,400 fewer people in state correctional facilities since Jan. 1, 2020, totaling 30,848 incarcerated New Yorkers as of Monday.

Incarcerated New Yorkers to be granted release after a parole hearing slightly declined since before the pandemic, with about 4,000, or 40%, of those interviewed released in 2019, compared to 2,280 people released on parole in 2021, or 36%. This year's numbers are not yet available.

Data broken down by age, race or other demographics is available through a Freedom of Information Law request.

Vacant parole board seats mean commissioners more often reach an impasse about a person's case, leading to longer wait times between hearing. Every incarcerated person who is due to have a parole hearing will appear before commissioners in the month and year scheduled at the time of their sentencing or previous parole hearings, regardless of the number of vacancies on the board, according to DOCCS.

"A fully staffed parole board could increase the board’s exceptional regional and professional diversity and provide even more coverage of office duties and during occasions of vacation, personal or family sick leave and emergencies," Connors said.

Two or three parole board members are assigned to one incarcerated person's case, but two members making the decision makes it more likely for them to fail to reach consensus, leaving people incarcerated for longer periods.

A parole hearing is rescheduled to the next month if commissioners fail to agree about a person's release. People who are not released after a parole hearing do not typically get another hearing for two years.

"When they don't have that time to really dig in, it can lead to needless denials of parolees and it can leave folks languishing behind bars for at least another two years," said TeAna Taylor, co-director of policy and communications with the Release Aging People in Prison campaign.

Taylor's father, LeRoy, has been incarcerated for second-degree murder for nearly 20 years since she was 10 years old.

"He's really used that time to change who he is from the inside out and really transform his life," said Taylor, of Schenectady.

Taylor's father, in his late 40s, will first become eligible for parole in 2026.

"Folks need to look within and decide if politics are more important than lives being lost needlessly, and for me, it's always going to be the latter," she said Monday.

The Fair & Timely Parole and Elder Parole bills to reform the state's parole system did not advance out of committee this session.

"The purpose of parole, currently, in New York state is very murky," Shapiro said. "Because we have a depreciation clause, that can keep people in prison despite of their transformation and who they are today. There needs to be a whole revamp of New York state parole if it's going to be a fair and effective system, because it's clearly part of our mass incarceration process."

The parole board's next scheduled meeting is July 25.

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo appointed 13 of the 15 current members. One was initially appointed under former Gov. David Paterson.