Over the last 22 years, New York state has shuttered 27 prison facilities amid a decline in its overall population of incarcerated. But left unanswered in many instances is what replaces those prisons once they close.

A report released this month by the Sentencing Project seeks to draw together what comes next for prisons once they close, the communities, and the formerly incarcerated.

"New York is among a handful of states that have reduced its prison population since it peaked in 2009," said Nicole Porter, the senior director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project and the author of the report. "The prison closures didn't follow right away, though. There was a lot of resistence to closing prisons."

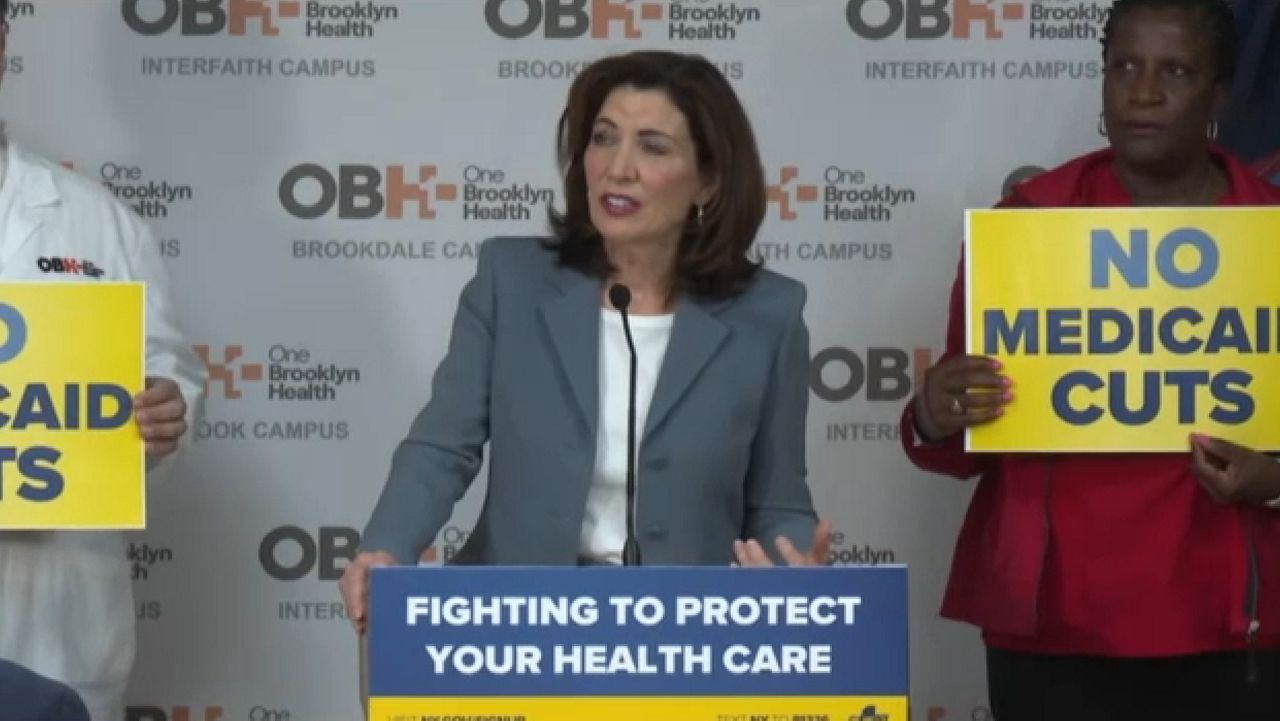

States are weighing a variety of options for what replaces a prison once it is closed. Many were built in economically struggling communities where jobs can be scarce, and the promise of the prison as a vehicle for economic development was never really fulfilled. Gov. Kathy Hochul this year created a new panel to find ways of re-purposing vacant prisons to make them economically viable.

"Certainly the location whether or not it's a rural area, a suburban one or an urban one, will influence what's possible for a prison," Porter said.

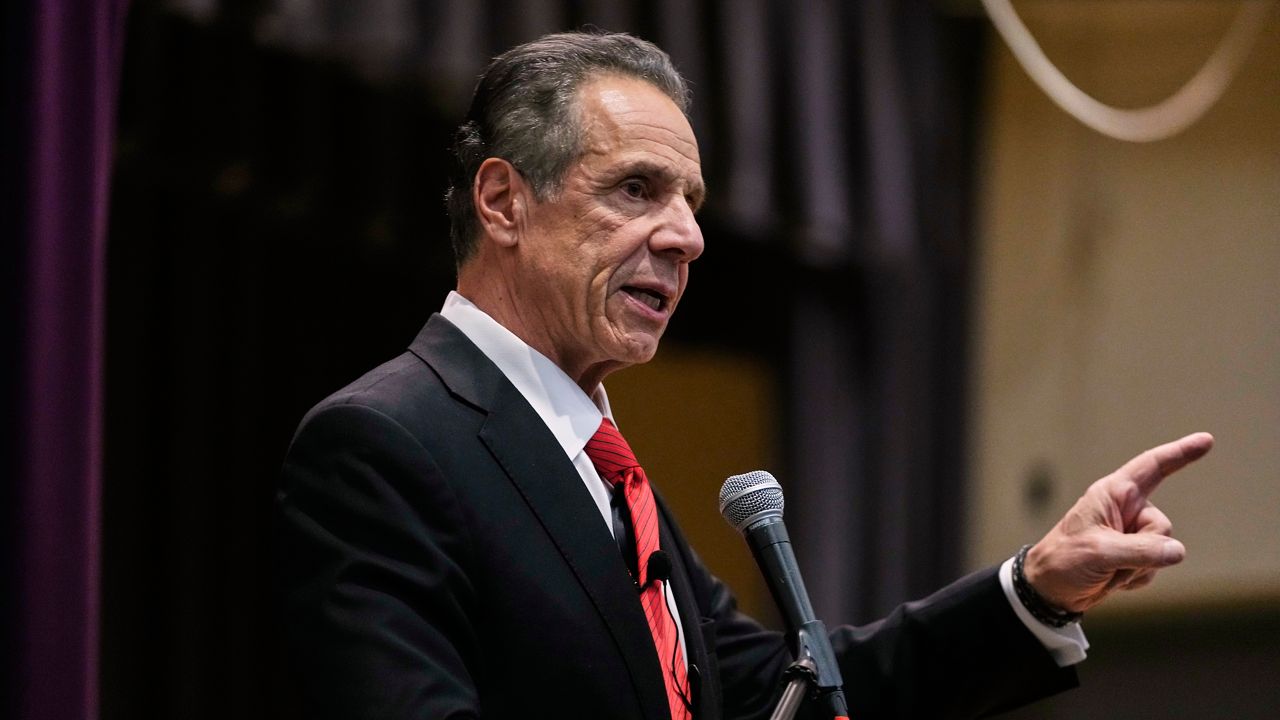

Prison closures and criminal justice policy have been fraught with politics in the last several years amid rising concerns over public safety. Republican candidate for governor Lee Zeldin has pledged to push for a repeal of a measure limiting the use of solitary confinement in prisons.

"The best thing to do is to sit down with those corrections officers and tell them what do you need?" Zeldin said. "Recruitment and retention is an issue. Assaults are on the rise."

But Porter said the current system is unmanageable and that New York's efforts to find ways of converting the prisons into sustained job creators can serve as a model. There have been 21 states to close prisons over the last several decades, representing a decline of 81,000 beds.

"The United States overbooked its prison system and in the midst of decarceration, the Untied States should really take steps to reduce its carceral footprint," Porter said. "Those steps can help reimagine what the United States can help promise to all its residents, including those most at risk of imprisonment."

State officials should not just consider the impact of economic development nost just on the communities that once hosted these prisons, but also the communities that have been impacted by criminal justice laws, she said.

"There are a range of consistuencies that need to be considered, not just the people in town where the prison is closed," Porter said, "but also in those high-incarceration zip codes in New York City and throughout the state."

_Pkg_CP_Hochul_Trump_DOT_CG_133247410_434)