As of the end of last year, 1,200 children have been successfully recovered through AMBER Alerts nationwide. But high-profile AMBER Alert cases in the Capital Region in the last year have sparked questions about how the system works, the length of time it can take to activate an AMBER Alert and if changes are necessary.

This past spring, an AMBER Alert was activated after the disappearance of a 10-month-old girl in Schenectady. It was later canceled, and law enforcement allege the baby died as a result of her mother's actions.

About five months prior, an AMBER Alert was activated after a 9-year-old girl was abducted from a state park in Saratoga County.

In both cases, that emergency alert was issued more than 12 hours after the child’s initial disappearance.

Spectrum News 1 set out to better understand how AMBER Alerts work in New York, and proposed changes advanced by lawmakers, by looking deeper into the Sept. 30, 2023, case that made national headlines.

A young girl on a family camping trip took a bicycle ride shortly after 6 p.m. last fall in Moreau Lake State Park. When she didn't return, her family went on an urgent search to find the missing child, who was last seen wearing a tie-dyed Pokémon shirt, dark-blue pants, black Crocs and a gray bike helmet.

Family members located the girls’ bike around 6:45 p.m. The police arrived not long after at around 7 p.m.

At around 11 p.m. a missing child alert was issued. But law enforcement didn't issue an AMBER Alert until 9:30 the next morning. Two days would pass before she was located.

“Part of me is like, don’t touch the AMBER Alert [system]. It’s fine the way it is. Don’t pursue anything," Jené Sena, the child’s aunt, said in a recent interview. "But then the other part of me is like, 'OK, it did take a bit too long.'"

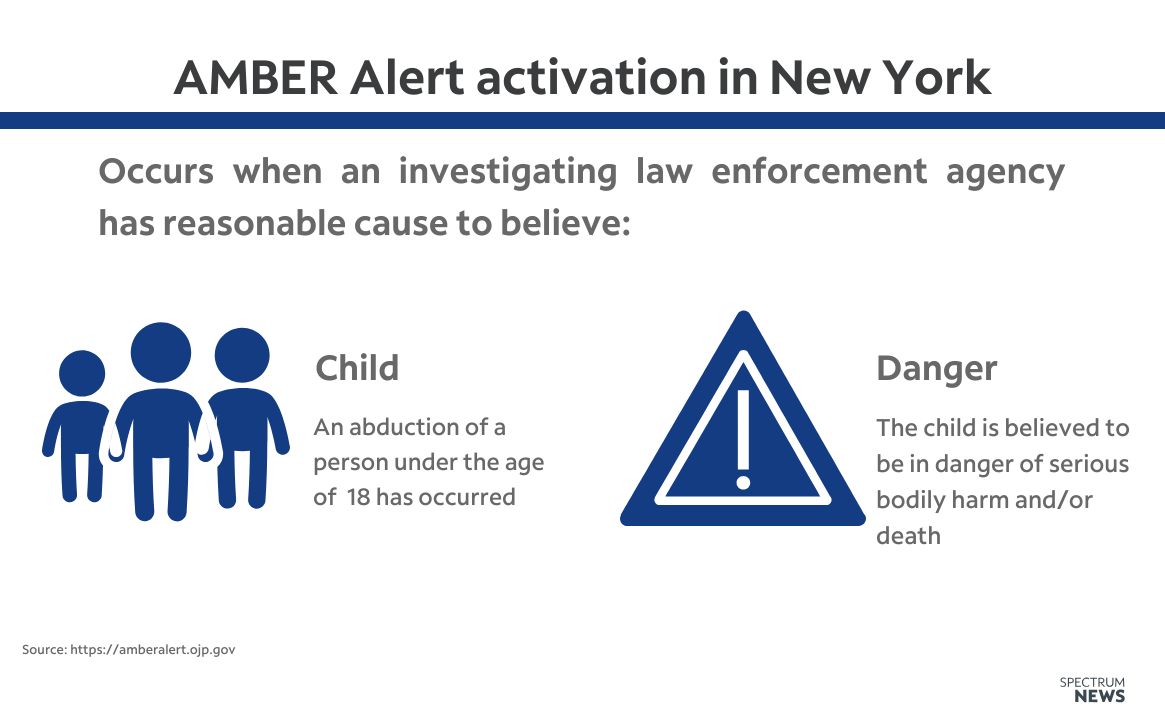

So what does it take to activate the New York State AMBER Alert Plan?

In the hours after her niece went missing, Sena says their family would come to learn exactly that.

“You can’t guarantee that a stranger took her because at that point, you don’t know…I mean they had to, like, rule all these things out,” Sena said.

In New York, an AMBER Alert can be issued when an investigating law enforcement agency has reasonable cause to believe a minor has been abducted and is in danger of serious bodily harm or death. The local law enforcement agency then contacts the New York State Police Special Victims Unit to request activation.

If criteria are met, state police will send out an AMBER Alert.

“They notify their primary distribution network," said Leemie Kahng-Sofer, executive director of case management at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). "That includes emergency alert systems, department of transportation signs, their various state resources and then we get the alert. We then redistribute the information to our secondary distribution network and to the wireless emergency alerts. The wireless emergency alerts (are) what the public is most accustomed to in terms of their cell phone alerts.”

In the overnight hours of Oct. 1, 2023, law enforcement equipped with drones, helicopters, underwater technology and bloodhounds scoured the state park property in search of Sena’s niece.

“Once the dogs lost her scent, it was pretty clear that an abduction had occurred,” Sena said.

It’s unclear how much time elapsed between that and the decision to issue an AMBER Alert. But from the time police arrived on scene, about 14 hours passed before the AMBER Alert was activated.

“Then, you have little information when you do actually go to issue the AMBER Alert. You don’t have a car description, you don’t have a license plate,” Sena said.

To that point, Kahng-Sofer said it’s important that AMBER Alerts contain enough descriptive information about the abduction for the public to help. While that’s not a requirement to activate New York’s system, the state’s plan does say activation may be impractical if available information is not specific enough.

“Really, what is crucial is getting that image of the child out there and the vehicle, if there’s a vehicle involved,” Leemie Kahng-Sofer said.

Available data from the U.S. Department of Justice annual AMBER Alert reports shows 3,264 AMBER Alerts were issued nationwide between 2006 and 2022. Of those, 435 cases were later determined to be unfounded or hoaxes. In that 16-year timeframe, data shows 684 cases were successfully resolved as a direct result of an AMBER Alert issued.

)

Kahng-Sofer called the system an invaluable resource. Others think there’s opportunity for change.

“Immediacy is of extreme importance for a missing person,” said state Sen. Jim Tedisco, who has been championing this cause for decades.

Tedisco helped create a first-in-the-nation program placing photos of missing children on Thruway toll tickets in the 1980s, and coauthored a book on the causes and consequences of child abduction in the 1990s.

He’s now co-sponsored a bill in the Senate that was first introduced by state Assemblyman Angelo Santabarbara.

“I think it’s our job to take a look at what happened," Santabarbara said. "Is there room for improvement?”

The bill seeks to create a formal process for a parent or legal guardian to request the early activation of an AMBER Alert, particularly in special cases.

“In some cases, it could be harsh weather. In some cases, it could be kids with disabilities. But there could be other unique circumstances,” Santabarbara said.

New York State Police declined to be interviewed as part of the story.

In the end, it wasn’t the AMBER Alert that brought Sena’s niece home, but a fingerprint on a ransom note that led to her rescue. The man who kidnapped her was sentenced in April to 47 years to life in prison.

New York lawmakers are not the first to try to change their AMBER Alert criteria. Sena can’t be sure it would have made a difference if the AMBER Alert had gone out sooner, but still hopes her niece’s story can inspire change.

In Texas, where the system began following the abduction and murder of Amber Hagerman, a law passed last year allowing local law enforcement to request an activation of the system, even if the criteria is not verified.

“I think that is a great solution, honestly," Sena said. "It gives a little more latitude for the people that are directly involved with the investigation to kind of make the call, or push things along a little faster.”