NEW YORK - Abby Faelnar had the idea of becoming a poll worker after coming across a post on social media. As an administrator at New York University, she is tested for COVID-19 regularly, which made her comfortable working the polls. But she was also thinking about issues at play this election cycle, including allegations of voter suppression and an increased awareness around systemic racism.

“I just didn't want to sit out and not do anything,” Faelnar, 32, said.

First-time poll worker Sheina Llanos cites those issues, along with the results of the last presidential election, as her motivation for signing up.

“With how the last four years have been under Trump, I just felt like I had to do something,” said Llanos, 36. “And it's hard as an individual to feel like there's ways to help, and this felt like at least one tangible way that I could contribute.”

Poll workers play a vital role in the election process. Their presence is often the crucial difference between a smoothly run polling site, and mass confusion and long lines. But in the past, it’s been difficult to recruit for this important, yet underappreciated, role. In fact, two-thirds of jurisdictions had a hard time recruiting enough poll workers on Election Day in 2016, compared to fewer than half of jurisdictions in 2008 and 2012, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. And with the threat of COVID-19, the shortage of poll workers, who tend to be middle-aged or elderly, is a major concern this election.

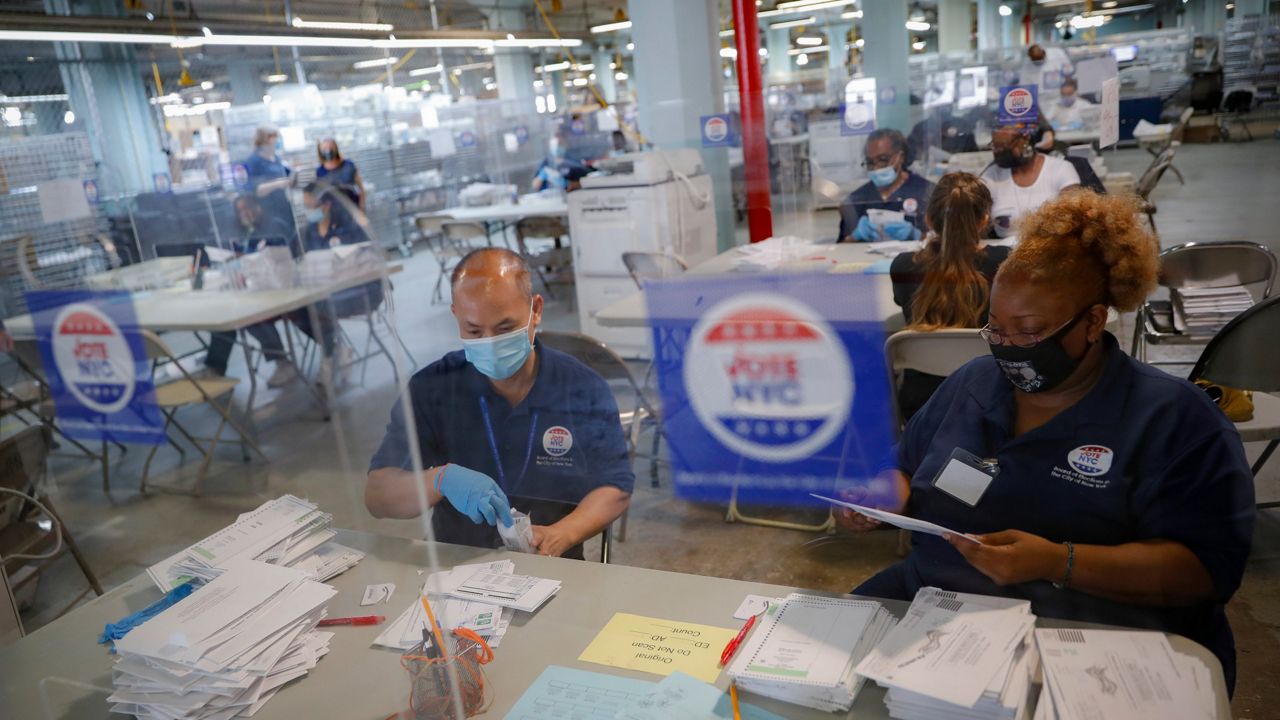

Not only has the pandemic made it harder to staff the polls with the typically older demographic of workers, but it’s created an urgency for mail-in voting across states and counties. But with worries about the Postal Service’s capacity to handle the onslaught of ballots, President Trump’s unfounded claims about the threat of voter fraud and a partisan debate about voting by mail, the demand for poll workers to ensure a fair and efficient election has surged.

This potential shortage is prompting younger people to sign up to work the polls for the first time. The organization, Power the Polls, which aims to recruit young, diverse populations, has signed up more than 25,000 people in New York City to work this election, according to a spokesperson for the group. Nationwide, it has recruited more than 500,000 potential poll workers since it launched this summer.

“The city board is going to have a much larger pool of applicants to call on,” said Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York, a watchdog organization that partnered with Power the Polls this year. “It gives them the flexibility to plan for how to handle large turnout and to have a lot of assistance.”

While the Board of Elections was unable to provide information on how many first-time poll workers signed up this year, Lerner attributes this wider pool of poll workers to the agency’s concerted effort to recruit new people.

“They actually recruited people as opposed to waiting for people to apply or only hiring people who are recommended by the political party,” she said. “They did social media outreach, they had a special application on the website, they did a lot of outreach.”

She said the social media efforts particularly resonated with young people.

After a quick online application, potential poll workers are able to sign up for one of the four-hour in-person trainings. The training starts off with a presentation, and trainees are given a manual to take home and study. It also involves practice on a ballot machine.

On Election Day, there will be 1,200 polling sites; early voting will take place at 88 locations, according to BOE spokesperson Valerie Vazquez. And while people like Lerner are happy with the agency's increased recruitment efforts, there have been critiques lodged at the BOE in the past, including whether it’s doing enough to train new poll workers in time this year.

“There's a frenzy of activity,” said John Kaehny, executive director of Reinvent Albany, an organization that advocates for an accountable and transparent city and state government. “People are working with a lot of energy, but the challenges are huge. In a good year, the Board of Elections is barely able to get it done. And this is a terrible year.”

The changes brought on by COVID-19 has introduced a number of factors increasing the difficulty of the BOE’s work. This includes a shortened recruitment timeline, implementing early voting for the first time in a presidential election, and changing the system to mail-in voting preference.

“Those three, big, new demands put on top of the fact that [the BOE] is a decrepit, and barely competent, political patronage machine — that's big, big challenges,” he said.

The seriousness and importance of their role is not lost on the new trainees.

“The person I was practicing on a ballot machine with — we both looked at each other and thought, ‘Wow, this is no pressure at all,’” Abby Faelnar said sarcastically. “You definitely feel a certain pressure to like get everything set up correctly, and processed accurately.”

Karlyn Murphy, who lives in Brooklyn, signed up for one of the trainings in her neighborhood.

“I've been following politics a lot more closely in the last few years since the last election and wanted to be more connected to my community,” Murphy explained. “In this pandemic, it's been nice to be out on the street and see my neighbors more.”

Becoming a poll worker has shifted how these first-timers think about the political process.

“It makes me appreciate it a lot,” said Murphy, 30. “There's a lot of people, hours and attention that goes into this.”

While concerns over the safety and fairness of the election process may be motivating some people to sign up, they say the training is reinstating their faith in this fundamental institution.

“There's so many rules, and the process is really intricately established,” said Llanos. “It gave me more confidence in the system in a way.”

After going through the appropriate training, you’re given the option to sign up to work one of the early in-person voting dates or the main Election Day on November 3. If you work on the third, you’re required to commit to the entire day from 5 a.m. to 9 p.m.

“I think I'll be exhausted, but I'm looking forward to the experience,” said Murphy.