New York state is in the midst of a deep dive for its Erie Canal history.

While the historic waterway is just 10 feet deep in most places, it is not on the canal system’s 363 miles where these artifacts are uncovered. Instead, the wrecks are being reclaimed on places like Seneca Lake and across other Finger Lakes where an expedition in search of shipwrecks is underway.

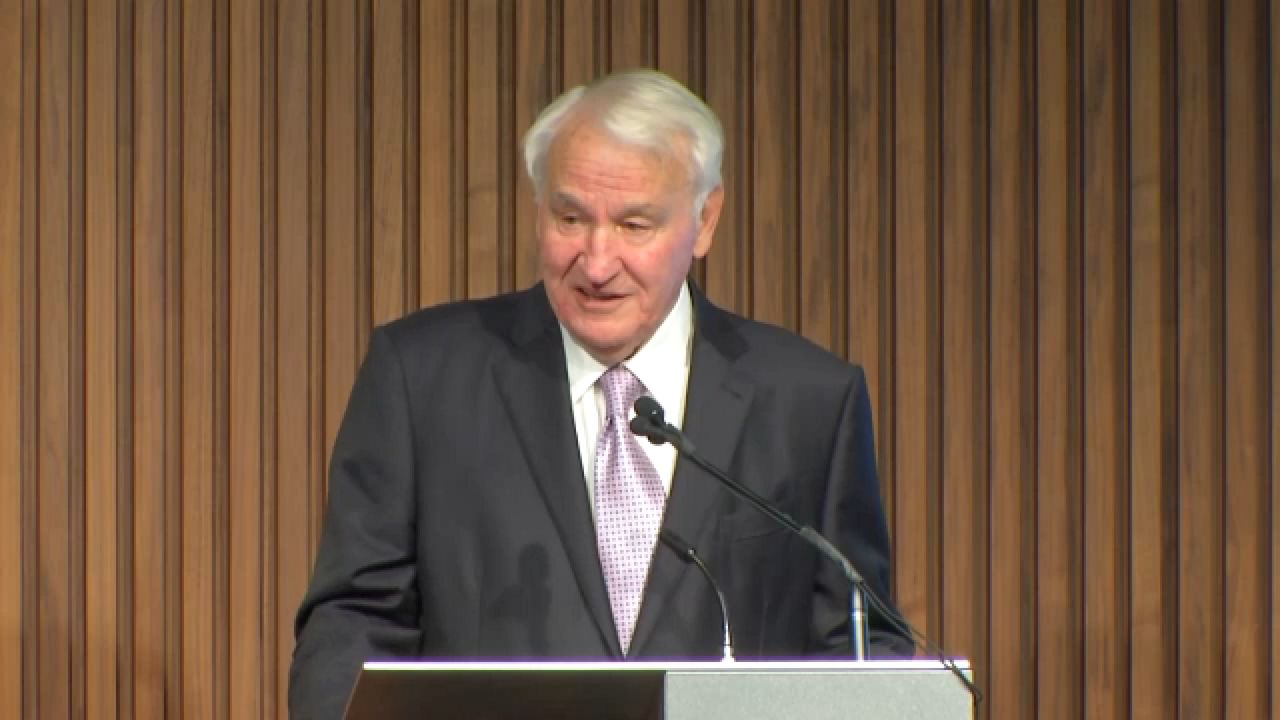

“It’s about learning more about the world we live in in the world we came from. It’s absolutely exciting to me,” said Art Cohn, lead maritime investigator of the Seneca Lake Archaeological & Bathymetric Survey, the effort that searches New York’s inland lakes for canal wrecks and more.

Cohn’s survey of Seneca Lake was actually launched in 2019, but the search for underwater wrecks began in July of this year. It uses sonar and underwater camera drones to rediscover the lake's history through its shipwrecks.

So much of it is linked to the Erie Canal, with commerce and transit running the length of Seneca's 38 miles during the nation’s canal era of the early and mid-19th century.

Art's team found 17 underwater wrecks by casting this tech in the Finger Lakes deepest body of water. The key: having a target. For Art and his crew, it was the search for a packet boat, the earliest vessel to traverse the Erie and deliver people, goods and freight from the nation’s interior to the world.

Through newspaper accounts, state records and local historical accounts, Cohn narrowed his packet search to Seneca Lake, the deepest of the Finger Lakes and a super-busy industrial route during the canal era. The Erie Canal system’s secondary canals, including the Chemung, Crooked Lake and Seneca-Cayuga canals, linked the Southern Tier and Pennsylvania coal country to the world.

The search for the packet boat, known to most today only through art depictions of the 19th-century craft, was Cohn’s primary target.

“We realized that Seneca Lake had so much commercial activity on it that it potentially contained a treasure trove of shipwrecks never been inventoried or seen before. And the cherry on the top of this cake was we found a packet boat. The long-elusive, now the only one known to exist,” Cohn said.

“These were the greyhound buses of their time,” said Brian Stratton, head of the NYS Canal Corporation, one of the supporters of the survey. “Taking passengers, families, all of those people traveling west. And local routes too.”

“We realized that we had stumbled into a veritable community of historic shipwrecks,” Cohn said, “And their legacies of tragedies from 150 years ago."

Cohn’s findings, supported by New York State, would teach the public about the Erie Canal's past during its bicentennial celebration that runs through 2025. The vessels, many covered in zebra mussels, are to Cohn documents, time capsules and informers of the past.

The survey ran into as many challenges as the vessels they mapped.

A rainy July raised the levels of the Erie Canal so high that the survey’s primary research vessel was not able to traverse the canal system. Faced with its first delay, Cohn and his team turned to a smaller boat and its two-person crew, Tim Caza and Dennis Gerber.

On the eighth day of the survey, the three headed to the west side of Seneca Lake near Dresden to capture on video a coal-hauling Erie Canal sailing craft that likely sank in 100 feet of water more than 150 years ago. They found the boat by chance during their normal survey sonar capture; a bonus to their original mapping.

We're going across the lake.

"We have not had the opportunity look at a lot of these canal boats, so this is an extraordinary opportunity," said Cohn, whose study of the boat indicated the craft was likely lost as it and several flat canal boats were pulled by a steam-powered tug boat up the lake from Watkins Glenn to Geneva.

A remote-operated vehicle (ROV) with a 500-foot spool of the fiberoptic line helped the expedition traverse all of the wrecks it mapped.

Minutes into the ROV’s assignment, it found the wreck, moving slowly around the wreck’s hull.

“Its transom is heavily railed, as you would expect to the sailing vessel. So this is giving all the appearances of a classic freight hauling Canal barge straight sides,” Cohn said as he looked into the ROV’s monitor. “It has a straight stern. It’s molded rounded bow. We’re trying to figure out what its last moments were like, and also if it has any unique construction features.”

Its last moments were like many of the boats lost on Finger Lakes like Seneca, especially shallow, flat canal boats. Sudden changes in weather-swamped packet and freight canal-era boats. As many as eight to 12 of the boats would be tied to one tugboat. Historians say as soon as one of the boats would take water, they’d be released from the tug. The families and crews on board left to fend for their freight, animals and belongings.

The ROV images from this sunken wreck also show what appears to be a statue emerging from the hull, but just as they begin to make out a hand jutting from the wreck, Art and his team lose the drone’s video signal.

A four-person fishing boat had drifted inside of the 300-foot range research boats are legally provided in New York state. One of the boat’s downriggers appeared to have snared the drone’s fiber cable.

Suddenly, Art's expedition was in jeopardy. While the anglers unhooked from the cable, the survey team jumped into action. Caza, the lead surveyor, donned a swimsuit and jumped into the lake to free the cable.

But it was too late. Razor-sharp lures from the downriggers appeared to slice the cable in at least two areas. The mishap froze the expedition’s video gathering. The men, jubilant just moments earlier, were deflated by the boaters’ lack of awareness.

“Kind of bums you out. Because with that cord being severed, that pretty much shuts you down 'til we get a replacement,” said Caza, who estimated reordering the technology from Hong Kong would take three weeks and close the window on his team’s availability to video record Seneca’s shipwrecks.

“What a shame,” Cohn said. “But you have to put it in perspective. We lose the chance to document these wrecks today this way. But the people involved in these wrecks we’re studying, they lost everything. Their animals. Their goods. On occasion, lives would be lost, including children. We’re disappointed, but we’re not losing perspective.”

Cohn’s team bounced back two days after their downrigger mishap. Using only sonar, they rediscovered nine known shallow shipwrecks near Watkins Glen as well as four unknown sunken craft-certain to be 19th-century canal boats.

The tales of those lost canal boats are what Cohn has been sharing all summer at free public events through the Finger Lakes. His findings, already being shared at the Finger Lakes Boating Museum and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, are also being supported by Tripp Foundation and the Hochul Foundation; the latter, operated by the family of Lt. Governor/soon-to-be governor Kathy Hochul.

They're tales Art Cohn will share now, through the Canal's bicentennial year of 2025, and beyond.

“The most important thing then we can do after we advocate find and learn about these vessels is to share the lessons and information,” Cohn said. “It’s an important story to remember, it’s an important story to get right and important story to share.”