More than three decades after a bomb pierced the evening sky over Lockerbie, Scotland, the Syracuse University community carries on a tradition to honor the 35 study-abroad students killed on Pan Am Flight 103.

The university’s annual Remembrance Week, which runs October 20-26, features a candlelight vigil, a special panel discussion, art exhibits, and exclusive access to documents related to the bombing.

RELATED | See a Full List of Events For This Year's Week of Remembrance

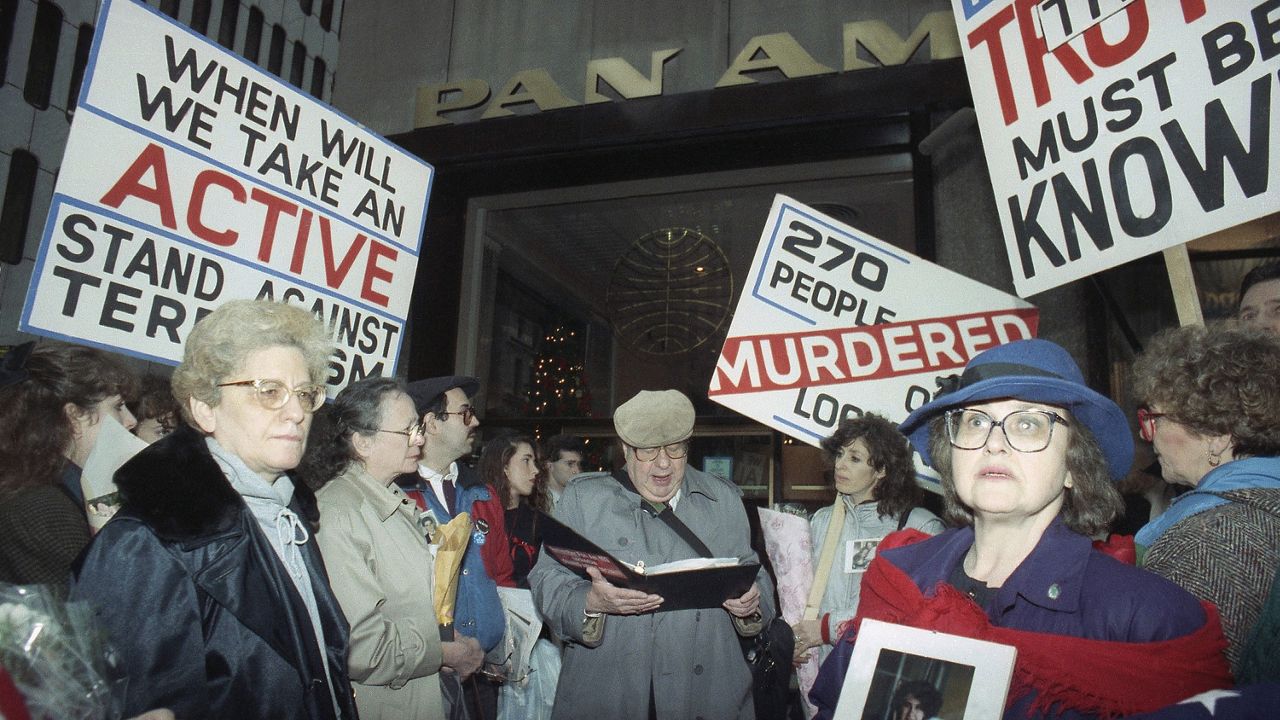

In all, 270 people died on Dec. 21, 1988, including the 35 SU students, two SUNY Oswego students, a couple from the town of Clay, and several people on the ground in Lockerbie.

This project combines new reporting by Spectrum News anchor Tammy Palmer with reporting done in 2008 by the late Bill Carey.

DOCUMENTING A TRAGEDY

In the months after the tragedy — with students and staff still traumatized and grieving — SU faced a dilemma: How should the murder of 35 students be acknowledged each year?

In many ways, SU was forced to navigate an uncharted path. At the time, few universities had faced horrific losses on this scale, and the threat of terrorism wasn’t a routine headline on nightly newscasts.

The decision to establish the Pan Am Archives in 1990 would prove to have a lasting and widespread impact. Archivist Vanessa St. Oegger-Menn is now part of a national task force creating tools and guidelines to help institutions and other archivists’ process grief-based materials in an era of mass shootings.

“Maybe everyone doesn’t have to figure everything out from scratch the way that we did in 1990,” St. Oegger-Menn explains.

A force behind the Pan Am 103 Archives, St. Oegger-Menn helped carry out the vision for a special exhibit in 2018, marking 30 years since the bombing. Initially, the archives had focused on the victims with direct connections to SU. Years later, the doors have opened to carefully document the lives of all 270 people killed.

More than 60 personal collections are stored at Bird Library on campus. Donations are rotated through changing exhibits on the sixth floor, including items found at the crash site. Visitors might see an alarm clock, a London tour guide, or one passenger’s baseball cap with frayed edges. There’s a spiral notebook with phone messages for the wife of Bill Daniels. One entry notes that a representative of Pan Am had called to report that her husband was likely on the flight and there were no survivors. Decades later, Daniels’ wife and daughter visited the archives to look at the notebook together.

As families ponder what to do with their loved ones’ belongings, donations to the archives are growing. A new generation of students — born long after the bombing — now have a window to the past.

“It’s becoming a historical point that most of them don’t have a personal connection to,” says St. Oegger-Menn. “There is a duty to these families and to this university to make sure that we don’t forget.”

CAPTURING THE MOMENT

Lawrence Mason remembers learning about the Pan Am 103 bombing like it was yesterday. He knows he was listening to music and wrapping presents, as Christmas was just a few days away, at the precise moment the phone rang.

He recalls the tone of the voice on the other end of the line, the questions he was asked, and the answers. The sharpness of those memories reflects the emotional impact of the sad news just delivered — news he was being asked to document.

In 1988, Mason was an assistant professor in the photography department at SU. He also happened to work for United Press International (UPI), coordinating pictures in Central New York. The call was from his state bureau chief. Mason was asked to immediately get photographs at Hendricks Chapel, where a memorial service had been quickly organized. As reports of the number of victims trickled in, Mason started to do the math.

“I was teaching one-fifth of every undergraduate coming into SU,” Mason says. “If I go to the chapel, I should be sitting with the students and the faculty mourning and grieving. I don’t think I can detach myself from the knowledge that I taught some of those people.”

Instead, he agreed to gather photos from a basketball game, where he noticed one of his students on the sidelines, Catherine Crossland, a cheerleader. She looked like she’d been crying so he asked how she was doing.

“Nobody knew any names yet, but she was very worried and she burst into tears and hugged a cheerleader who was right by her side,” Mason says.

Hours later, when he went to a dark room to develop some film, Mason noticed that his UPI partner had captured the cheerleader’s hug as tears streamed down her face. They knew it perfectly captured the emotions of students, but she hadn’t been asked for permission to use the photo. There was no e-mail back then and no cell phones to offer instant contact.

“We had some ethical discussions,” Mason says. “It finally just came down to the thought: She put herself willingly in the public eye. I had a license to photograph the game. Whatever happened inside the Dome, it was fair.”

He called his UPI contacts, told them to drop everything for a picture that he was sure would be used around the world. It was. Initially, it seems Crossland was upset that a raw personal moment was on display for strangers. Eventually, Mason said she grew to understand that her image became a symbol of what everyone on campus was feeling at that moment.

Years later, Mason would take his students to Scotland to document the aftermath of the explosion that rattled the town of Lockerbie. Along the way, his view of teaching changed.

“I think I’m a better, more compassionate professor because of Pan Am 103,” he says. “From one day to the other, I may never see them again.”

LOOKING FOR THOSE RESPONSIBLE

Soon after the bombing, police and military fanned out on foot. They’d eventually scour hundreds of square miles.

It was the largest murder investigation in British history. In the end, it all came down to a piece of evidence so tiny it would fit on a fingertip.

After initially focusing on a possible Iranian connection, more attention was turning to Libya and its leader, Moamar Qaddafi. The pattern of Libyan action and U.S. response had been building throughout the 1980s.

.png)

In 1989, investigators in Scotland discovered some clothing fragments. Embedded in them was a tiny piece of what had been a circuit board commanding a timer that set off the explosion aboard Pan Am 103. It was a brand of timer sold to Libya.

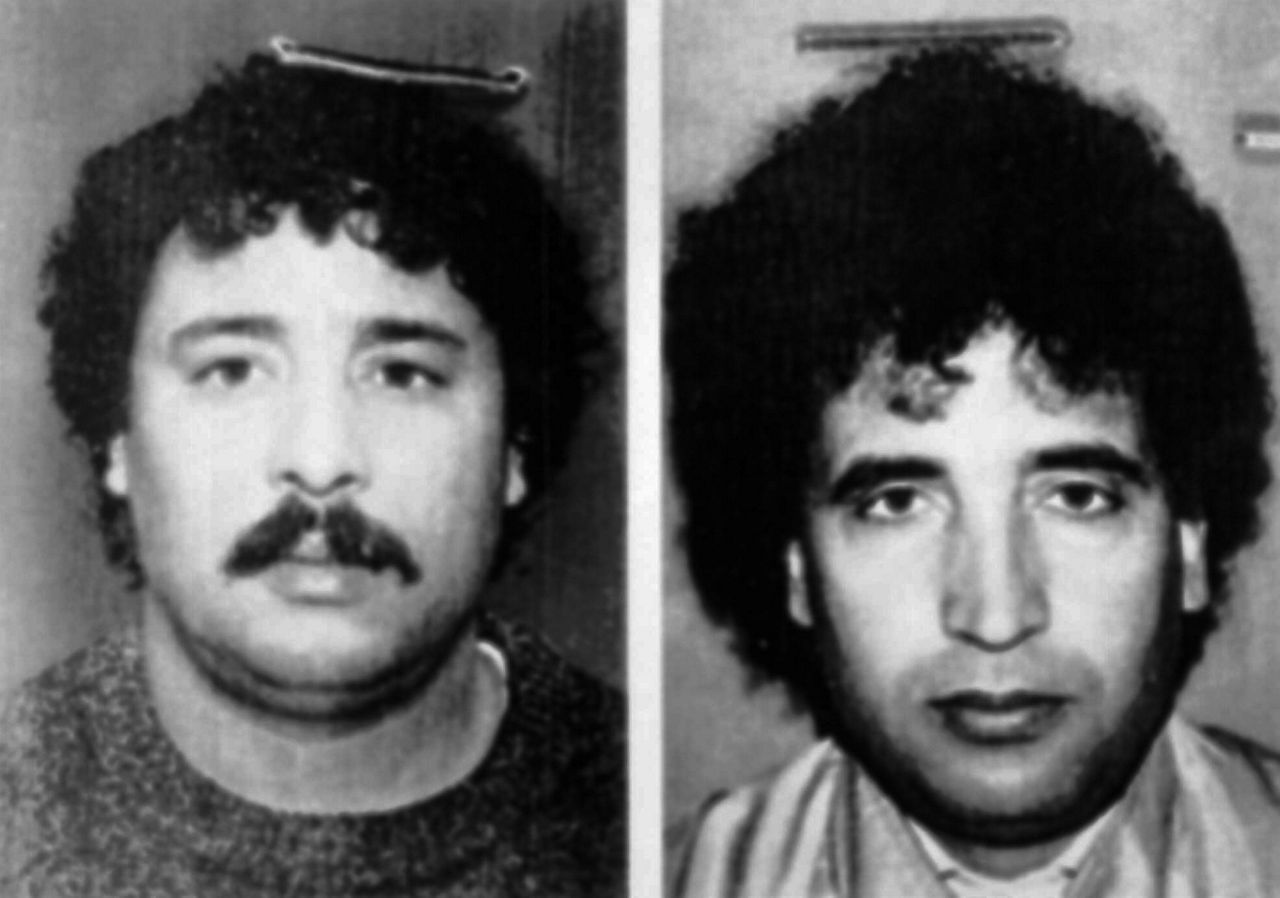

Forensics experts traced the clothing to a shop in the island nation of Malta. The owner of the shop identified the man who had purchased the clothes. He turned out to be a low-level operative in Libyan intelligence named Abdel Basset al-Megrahi.

A second Libyan charged was Khalifa Fhima, a former official of Libyan airlines at Malta’s Luqa Airport.

“By using stolen Air Malta baggage tags, the defendants and their co-conspirators were able to route the bomb-rigged suitcase as unaccompanied luggage,” said then-acting Attorney General William Barr in November 1991.

The Justice Department claimed the bomb, hidden in a suitcase, had been placed aboard an Air Malta jet to Frankfort, Germany, where it was loaded aboard a feeder Pan Am flight that eventually found its way into the cargo hold of Pan Am 103 in London.

It took years and tough United Nations sanctions, but Libya’s government eventually handed over al-Megrahi and Fhima for an unusual trial.

“I wanted to kill them. If I could have gone and sat there with an Uzi, I would have shot them dead on the spot,” said Susan Cohen, the mother of a Flight 103 victim. “No regrets, even if I got shot for it. And you want to know something? I still feel the same way.”

When the final verdict came 12 years after the bombing, the three-judge Scottish panel found al-Megrahi guilty and acquitted Fhima. Al-Megrahi would be handed a life sentence in Scottish prison.

The case came to a close at Camp Zeist in January 2001.

“I view, in some ways, Pan Am 103 as an opening skirmish or battle in the terrorism wars of the last 20 years,” said Paul Hudson, father of a Flight 103 victim. “There have been a number of major battles since then, some of which the U.S. has won, some of which we’ve lost.”

IF GEO-POLITICS WAS FATE

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi is still the only person ever convicted in the bombing but he never served his full sentence. In 2009, a doctor claimed al-Megrahi would likely die in a few months due to prostate cancer. He was allowed to leave prison under a Scottish law offering compassionate release for prisoners with terminal illnesses.

Crowds greeted al-Megrahi upon his return to Libya. Critics of the release suspect it had more to do with politics than compassion.

“The British, the rumor was, for an oil deal with Libya, released him early,” said U.S. Senator Charles Schumer. “The parents were so upset about that, so upset, the parents of the Syracuse students and everybody else.”

Schumer was among those to release a special Senate report in 2010 on the matter called “Justice Undone,” which suggested the Scottish government was pressured by the United Kingdom.

“[A]t the time of al-Megrahi’s release, BP was negotiating a $900 million oil exploration deal that would secure a much-needed reliable source of energy for the U.K. Keeping al-Megrahi in prison threatened this oil agreement, as well as other profitable trade deals and investments with Libya,” one section of the report stated.

The report also found that al-Megrahi’s three-month prognosis was inaccurate and unsupported by medical science. It suggested that respected cancer specialists did not believe the prisoner had three months to live. Instead, the Scottish government based the decision for a compassionate release on opinions from general practitioners who did not have an expertise in prostate cancer. Ultimately, al-Megrahi survived more than two-and-a-half years, spending that time home with family.

He also outlived Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who was violently killed in 2011 during an uprising. While some see Gaddafi’s death as a form of justice for Pan Am 103 victims, the turbulence in that region created more roadblocks in the ongoing investigation.

“Libya has gone through a tremendous amount of convulsions in the last 10 years. That’s really kind of hampered things, I think to some extent,” says U.S. Rep. John Katko. “Gaddafi is no longer around obviously. The country has been devolved into chaos, at least in certain regions in the country. There are a lot more terrorist influences over there as well. So, that makes the investigations that much more difficult.”

In 2015, the BBC reported that the Scottish government had named two new suspects, both reportedly behind bars in Libya at the time. Abdullah al-Senussi is the former Libyan intelligence chief under Gaddafi. Mohammed Abouajela Masud is a suspected bomb maker. Tracking them has been a challenge.

While Sen. Schumer would not offer details, he did say Masud is still part of an active investigation.

Editor's note: The Department of Justice announced charges against Masud, identified by the DOJ as Abu Agila Muhammad Mas’ud Kheir Al-Marimi, on Dec. 21, 2020. He was taken into custody in December of 2022.

MYSTERIES REMAIN

But not everyone is convinced they’re on the right trail. Over the years, an entirely different theory has emerged about whom, and which country, were responsible.

In July 1988, a U.S. warship came under attack by Iranian gunboats in the Persian Gulf. In the midst of the confrontation, the crew aboard the U.S.S. Vincennes spotted what it believed to be an approaching Iranian fighter jet closing in on their position. The U.S. response was lethal.

It wasn’t long before the Vincennes crew realized they had made a tragic mistake. It was not an Iranian fighter jet, but an Iranian passenger jet — with 290 people onboard.

There was a quick promise of Iranian revenge.

In the months to come, intelligence agencies would report a series of meetings, organized by a leading Iranian government radical named Ali Akbar Mohtashami-Pur. Among those in attendance was Ahmed Jibril, leader of a splinter Palestinian group known as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). Jibril was a close ally of Syrian President Hafez Assad.

Jibril's deputy was Hafez Dalkamoni, a man being closely watched by German police. Police knew of a plot to bomb aircraft flying out of Frankfurt. When they made their move, Dalkamoni and several others were arrested. Weapons were found, including a bomb hidden in a radio cassette player. There were indications that five bombs were produced. Only four are recovered.

A man with close ties to the PLFP-GC was Mohammed Abu Talb. Talb had visited Frankfurt and was later spotted in Malta, shortly before the Lockerbie bombing. At his home, police later found a calendar with the date — December 21, 1988 — circled.

Did Iran pay the PFLP-GC to exact its revenge? An airliner for airliner?

“There is, indeed, a paper trail of money going from Iranian sources, through various channels, into the bank account of the PFLP-GC. And that trail of money starts two days after Pan Am 103 was destroyed,” said Robert Black, a professor of law at Edinburgh University.

The man who headed the Scottish side of the case against Libya says it’s possible the Libyan agents, knowing of the Frankfurt arrests, may have used details of that plot to cover their own moves, including housing the bomb in a Toshiba cassette player.

Relatives of those who died in Lockerbie sense that the case against the two Libyans was far from a final answer.

“Other people involved have not been punished. So no, total justice or even a total semblance of justice has not been done,” said Robert Hunt, the father of a Pan Am 103 victim.

“Were those two implicated? Yeah. Were they part of the conspiracy? I believe they were. But I believe the tentacles of that investigation should have reached far further,” said Jeanine Boulanger, the mother of a Pan Am 103 victim.

LOCKERBIE FINDING THEIR WAY BACK

While families in Lockerbie don’t like to talk about the tragedy of Pan Am 103 with outsiders, they often make exceptions if you’re from Syracuse. That’s why professor and photographer Lawrence Mason has been allowed to see the stages of their recovery up close. He has visited Scotland more than a dozen times.

The reception with each trip is summed up with one story. Mason recalls getting a tap on the shoulder from a stranger, who wanted to know if he was from Syracuse.

“He stuck out his hand and he gave me a very, very strong, warm handshake and a long handshake and he said to me, ‘You will always be welcome in this town,’” Mason said.

Early on, his view of the town was limited to crash sites and memorials. But a former student who was raised in Lockerbie suggested that Mason look beyond the wreckage. The advice inspired him to begin documenting everyday life in a photo book, Looking for Lockerbie.

Recently, Syracuse University’s Chancellor Kent Syverud appointed Mason as the first-ever Remembrance and Lockerbie Ambassador. It’s an opportunity to keep sharing the story of Pan Am 103 through the eyes of a faculty member who lost several students on the flight. It’s also an opportunity to nurture a bond between Syracuse and Lockerbie.

Each year, a couple of students from Lockerbie are invited to study at SU to bring another perspective to a shared story of tragedy and healing. In turn, Mason regularly heads overseas, visiting the locals he has come to know well and meeting the next generation of Lockerbie neighbors. SU’s mascot, Otto, tagged along for one trip abroad, delighting some students with high-fives during a school assembly.

“I heard some younger kids after their encounter with Otto,” Mason said. “One of them said to a friend, ‘This is the greatest thing that ever happened to me in my life.’”

Mason has measured the Scottish town’s progress over the decades through their ability to express joy. The town didn’t put up Christmas lights for a decade after the bombing.

“My conclusion was it was the children who had never experienced Flight 103, who were born after it, who taught their parents how to smile again,” he said.

REMEMBERING STILL

Even if all the answers were known, the wound of the lives lost still remains deep — from Central New York to the grounds of Lockerbie. It doesn’t get any easier as the years go by and generations of students pass through SU, a journey 35 people were never able to complete.

Katie Berrell never met her uncle, Steve, but she knows his story. The youngest in the family, he transferred to SU to follow in his older brother’s footsteps. She has seen the photos of his semester in London.

“We have pictures of him all over the house. My grandmother actually, she wears either a pendant or a pin of him every single day with his picture in it,” she said. “So, I grew up just knowing him, even his face through that."

On the 30th anniversary of the bombing that claimed Steve Berrell’s life at the age of 20, his niece would learn much more about his life, his death, and the power of remembering the past.

Each year during October’s Week of Remembrance on campus, 35 seniors are chosen as “remembrance scholars” to represent the Pan Am 103 victims who were studying abroad with SU. As a remembrance scholar, Katie Berrell represented her uncle. It’s a role she describes as a lifetime commitment.

In this role, Berrell had the opportunity to meet the Scottish woman who cleaned her uncle’s belongings and sent them home to his family. One of his sweaters is kept under his niece’s bed. She’s still learning things about him – and herself.

“You know, I think about it every time I get on a plane,” she said. “They just got on a plane. They thought they were coming home for Christmas. Your life can change in the flash of a second.”

See the full list of 2019-20 Remebrance Scholar recipients here.