NEW YORK (AP) — Speaking from the Senate floor for the first time, Kamala Harris expressed gratitude for a woman on whose shoulders she said she stood. In her autobiography, Harris interspersed the well-worn details of her resume with an extended ode to the one she calls "the reason for everything." And taking the stage to announce her presidential candidacy , she framed it as a race grounded in the compassion and values of the person she credits for her fighting spirit.

Though a decade has passed since Shyamala Gopalan died, she remains a force in her daughter's life and her White House bid. Again and again in the campaign, those who gather around the California senator are hearing mention of the diminutive Indian immigrant the candidate calls her single greatest influence.

"She's always told the same story," says friend Mimi Silbert. "Kamala had one important role model, and it was her mother."

Her mother gave her an early grounding in the civil rights movement and injected in her a duty not to complain but rather to act. And that no-nonsense demeanor on display in Senate hearings over special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and more? Onlookers can credit, or blame, Gopalan, a crusader who raised her daughter in the same mold.

Appearing in New York recently, Harris said there were two reasons she was running for president. The first, she said, was a sense of duty to restore truth in justice in the country at an inflection point in history. The second: a mother who responded to gripes with a challenge.

"She'd say, 'Well, what are you going to do about it?'" Harris told the crowd. "So I decided to run for president of the United States."

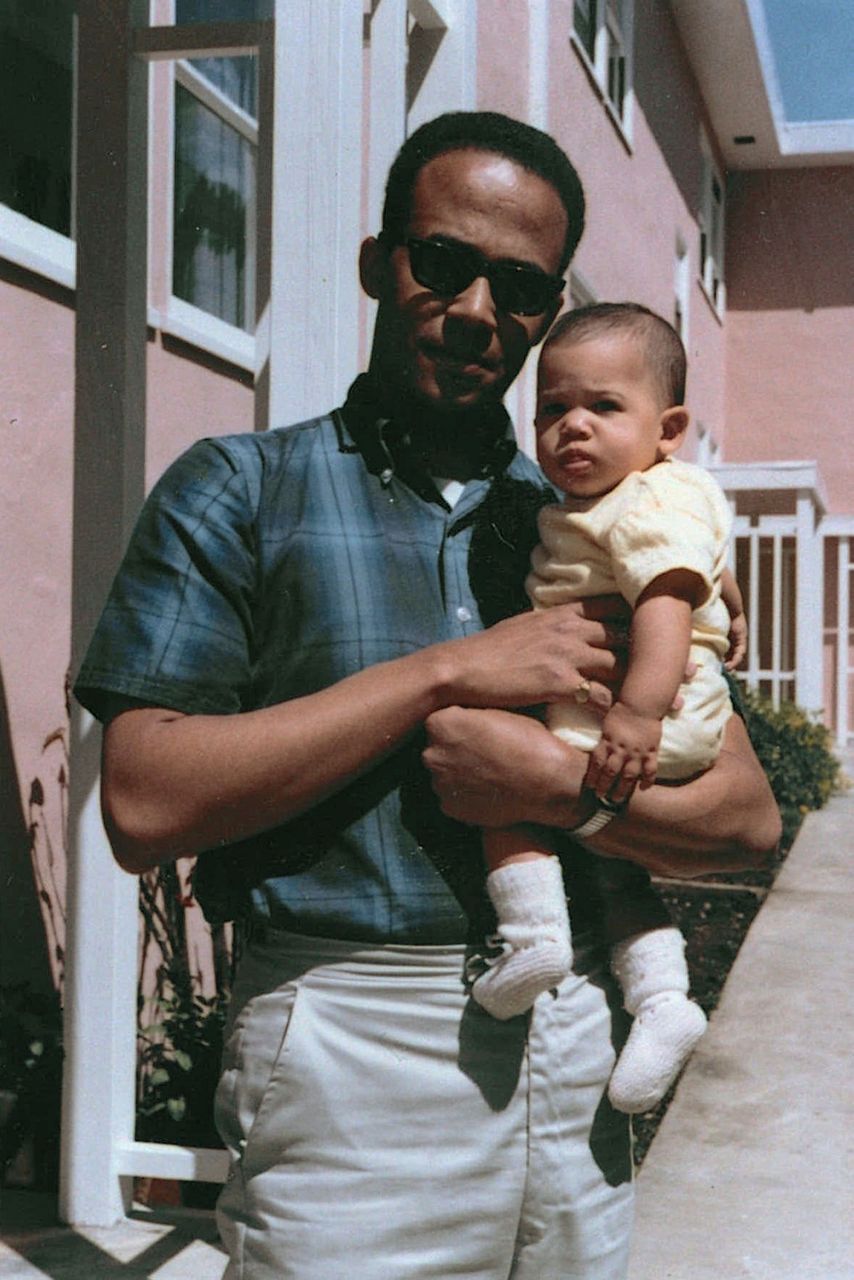

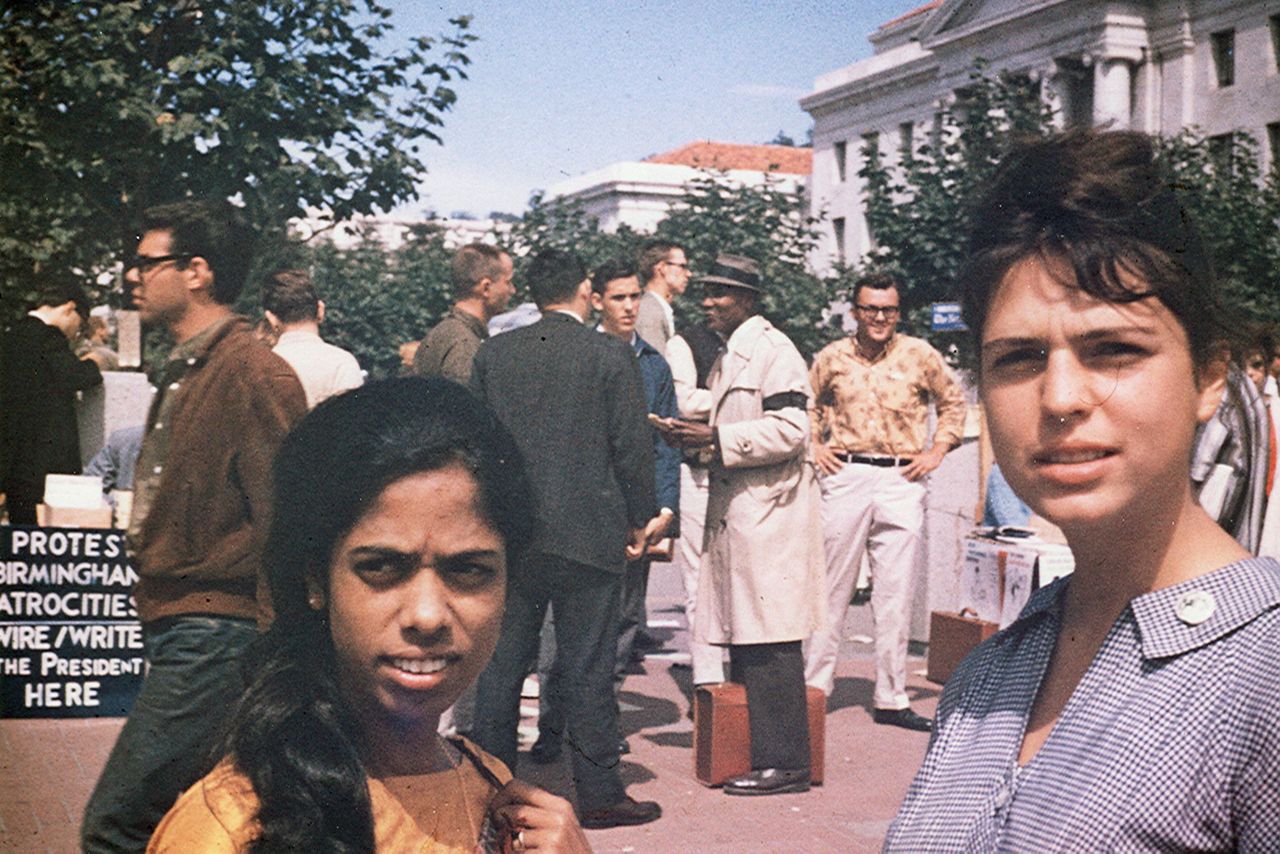

Harris' parents met as doctoral students at the University of California, Berkeley at the dawn of the 1960s. Her father, a Jamaican named Donald Harris, came to study economics. Her mother studied nutrition and endocrinology.

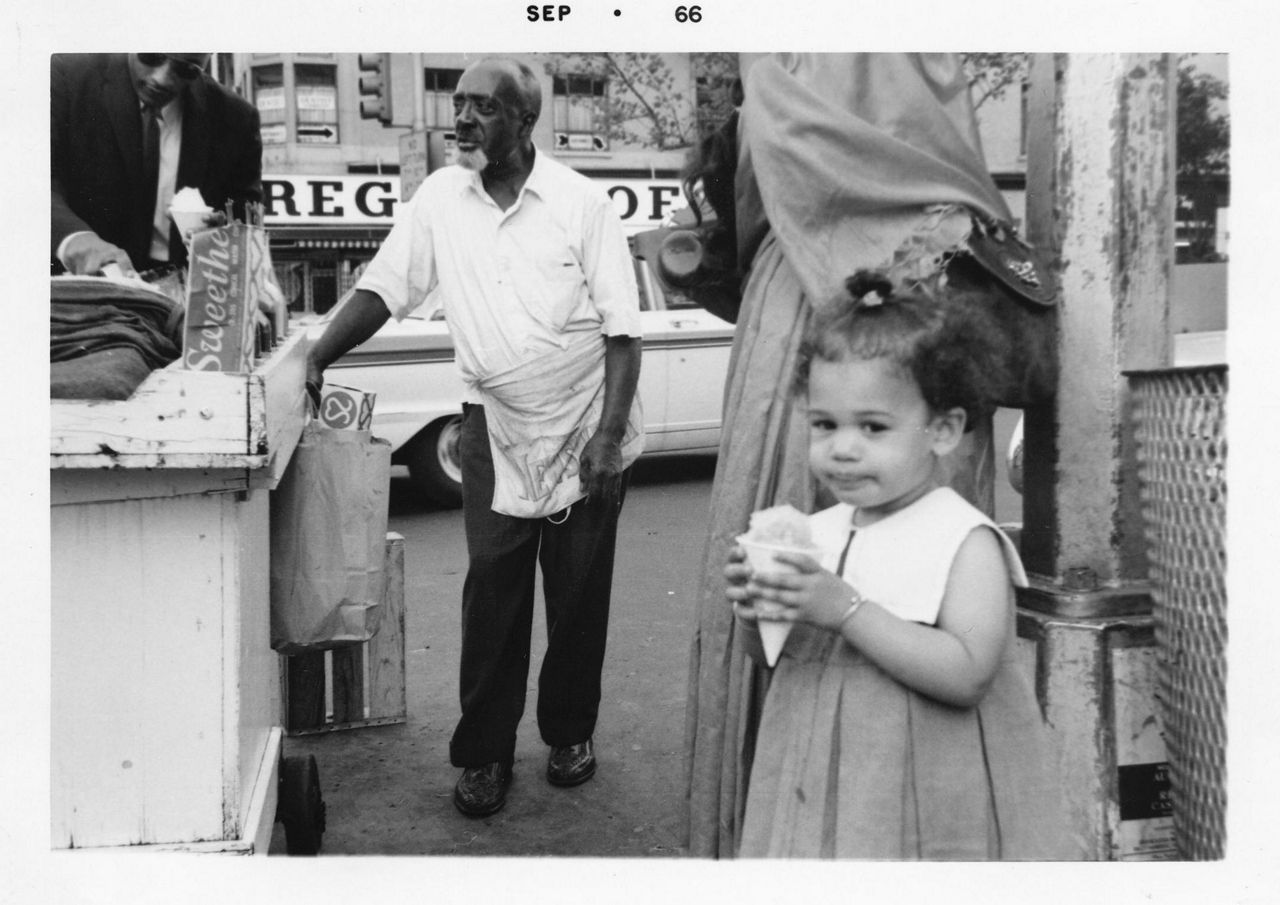

For two freethinking young people drawn to activism, they landed on campus from opposite sides of the world just as protests exploded around civil rights, the Vietnam War and voting rights. Their paths crossed in those movements, and they fell in love.

At the heart of their activism was a small group of students who met every Sunday to discuss the books of black authors and grassroots activity around the world, from the anti-apartheid Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa to liberation movements in Latin America to the black separatist preaching of Malcolm X in the U.S.

A member of the group, Aubrey Labrie, says the weekly gathering was one in which figures such as Mao Zedong and Fidel Castro were admired, and would later provide some inspiration to the founders of the Black Panther Party. Gopalan was the only one in the group who wasn't black, but she immersed herself in the issues, Labrie says. She and Harris wowed him with their intellect.

"I was in awe of the knowledge that they seemed to demonstrate," said Labrie, who grew so close to the family that the senator calls him "Uncle Aubrey."

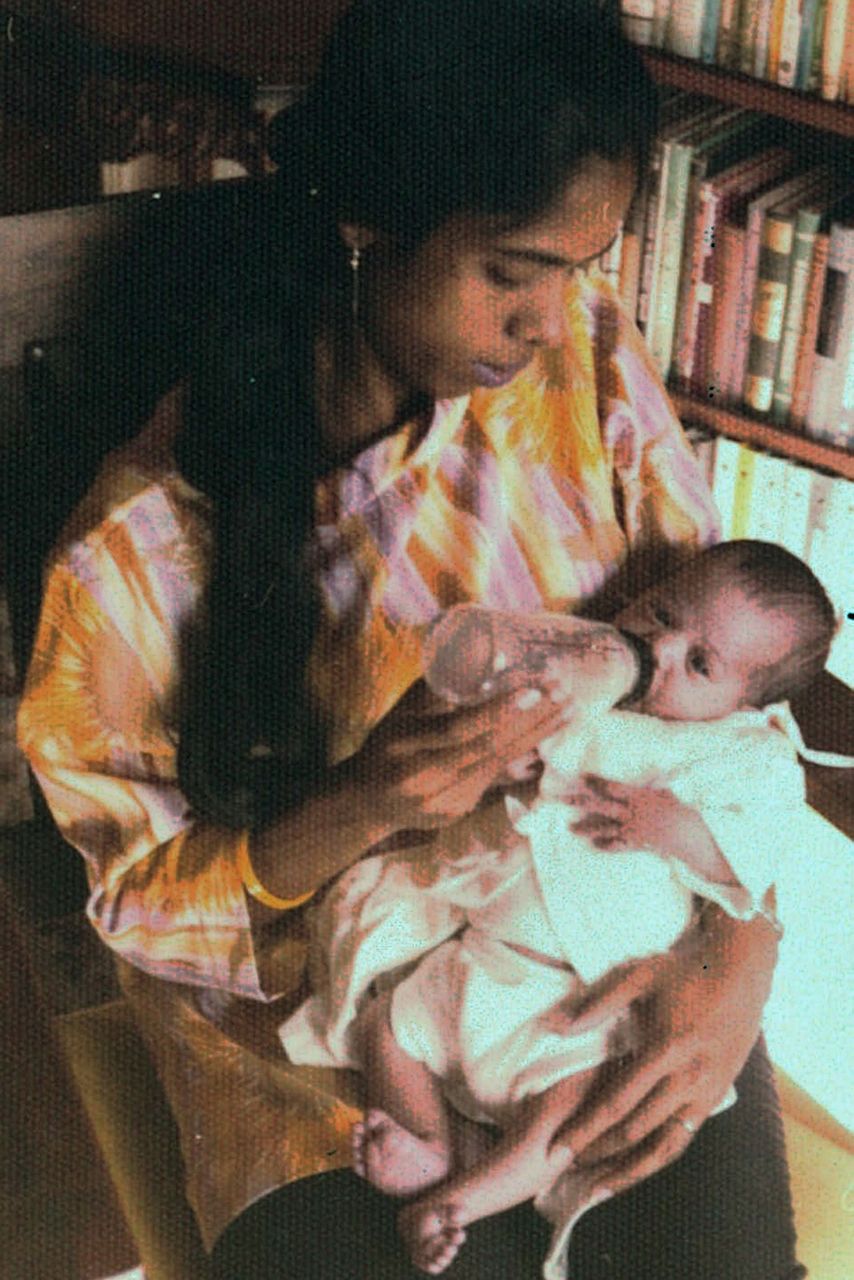

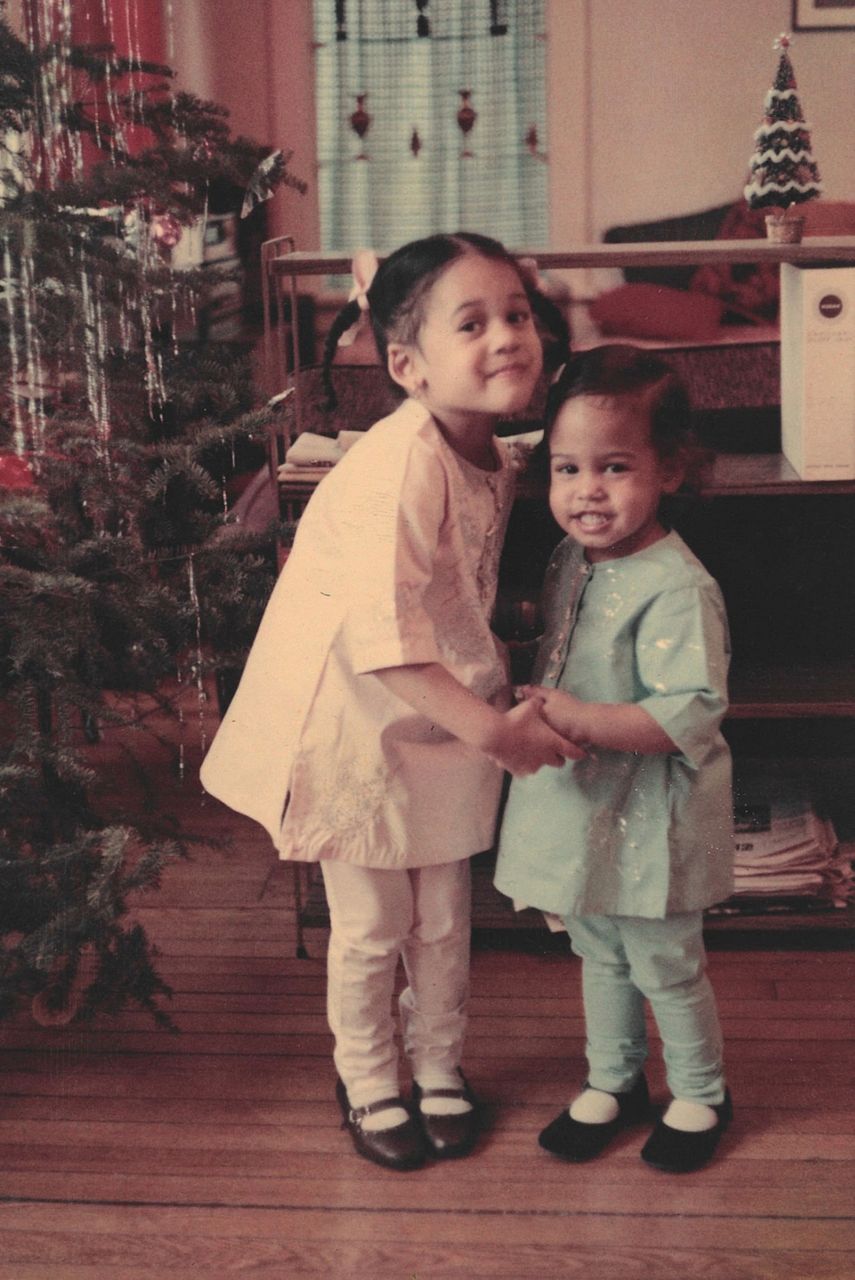

The couple married, and Gopalan Harris gave birth to Kamala and then Maya two years later. Even with young children, the duo continued their advocacy.

As a little girl, Harris says she remembers an energetic sea of moving legs and the cacophony of chants as her parents made their way to marches. She writes of her parents being sprayed with police hoses, confronted by Hells Angels and once, with the future senator in a stroller, forced to run to safety when violence broke out.

Sharon McGaffie, a family friend whose mother, Regina Shelton, was a caregiver for the girls, remembers Gopalan Harris speaking to her daughters as if they were adults and exposing them to worlds often walled off to children, whether a civil rights march or a visit to mom's laboratory or a seminar where the mother was delivering a speech.

"She would take the girls and they would pull out their little backpacks and they would be in that environment," says McGaffie.

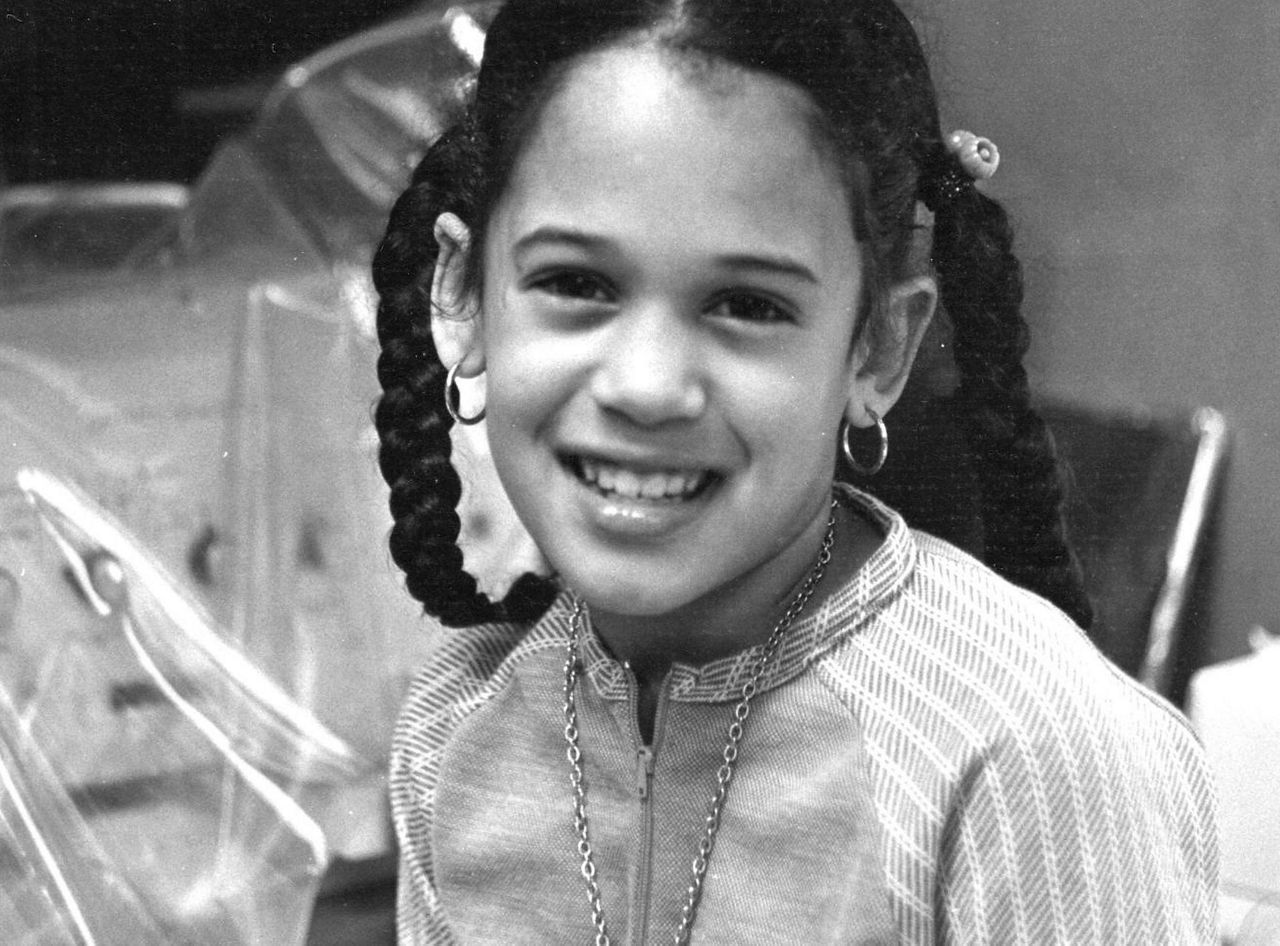

A few years into the marriage, Harris' parents divorced. The senator gives the pain of the parting only a few words in her biography. Those who are close to her describe her childhood as happy, the smells of her mother's cooking filling the kitchen and the sound of constant chatter and laughter buffeting the air.

The mother's influence on her girls grew even greater, and friends of Harris say they see it reflected throughout her life.

As a kindergartner, Stacey Johnson-Batiste remembers Harris coming to her aid when a classroom bully grabbed her craft project and threw it to the floor, which brought retaliation from the boy. He hit the future politician in the head with something that caused enough bleeding to necessitate a hospital visit, cementing for Johnson-Batiste a lifelong friendship with Harris and a view of her as a woman who embodies the ethics of her mother.

"Even back then," Johnson-Batiste says, "she has always stood up for what she thought was right."

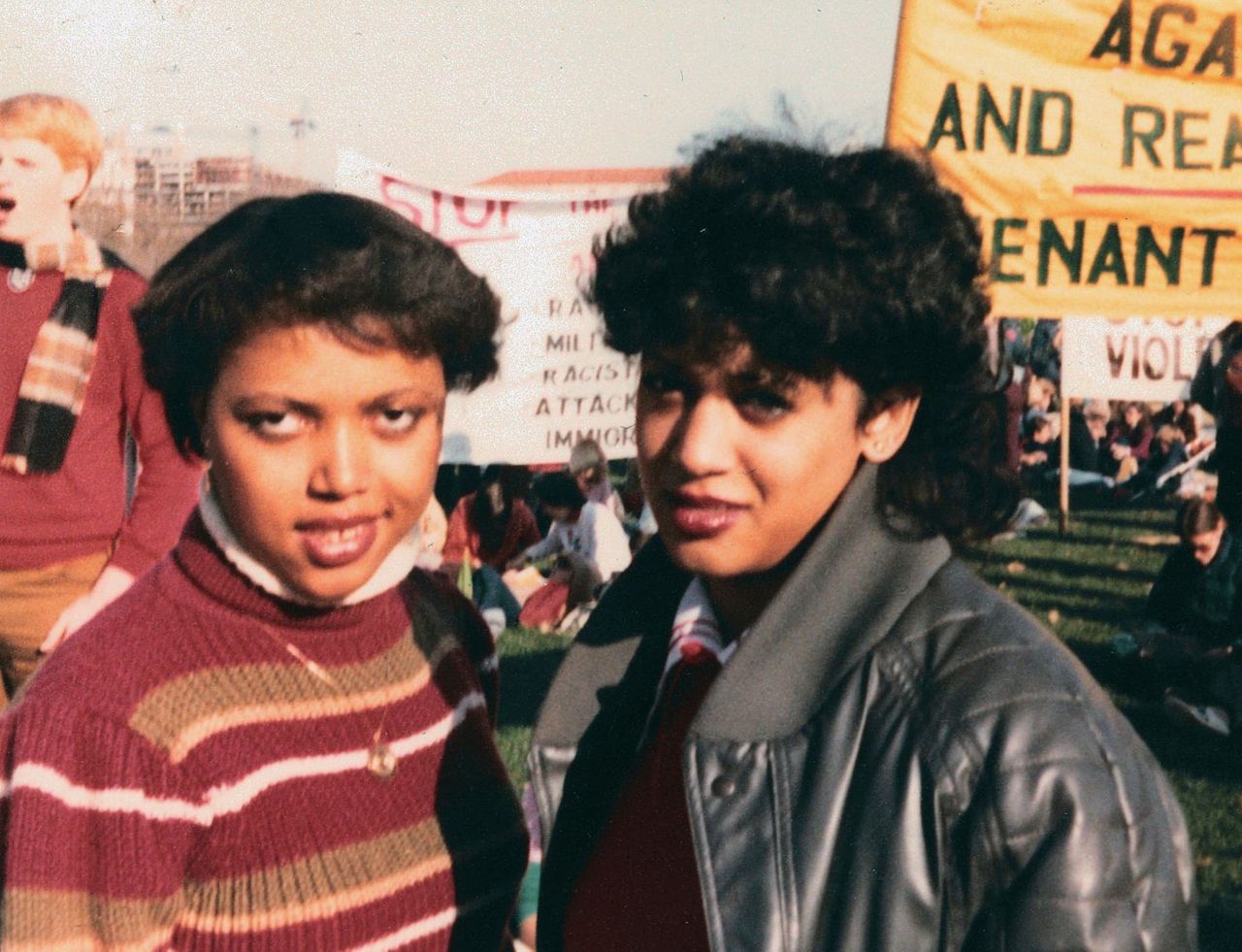

As a teenager, after her mother got a job that prompted a family move to Montreal, Harris began seeing how she could achieve change in ways small and large. Outside her family's apartment, she and her sister protested a prohibition against soccer on the building's lawn, which Harris says resulted in the rule being overturned. As high school wound down, she homed in on a career goal of being a lawyer.

Sophie Maxwell, a former member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, says Harris wasn't choosing to eschew activism but rather to incorporate it into a life in law: "Those two things go hand in hand."

In college, at the historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C., Shelley Young Thompkins recalls a classmate who was certain of what she wanted to do in life, who was serious about her studies and who put off the fun of joining a sorority until her final year even as she made time for sit-ins and protests. Thompkins and Harris both won student council posts.

In her new friend, Young Thompkins saw a young woman intent on not squandering all that her mother had worked to give her.

"We were these two freshmen girls who want to save the world," she says.

From there, Harris' story is much better known: a return to California for law school; a failed first attempt at the bar; jobs in prosecutor's offices in Oakland and San Francisco; a brazen and successful run at unseating her former boss as district attorney; election as state attorney general and U.S. senator; and her run for president.

Each step of the way, friends point to the influence of Gopalan Harris as a constant.

Andrea Dew Steele remembers it being apparent from the moment they sat down to craft the very first flyer for Harris' first campaign for public office.

"She always talked about her mother," Dew Steele says. "When she was alive she was a force, and since she's passed away she's still a force."

Dew Steele remembers when she finally met Gopalan Harris at a campaign event. It immediately struck her: "Oh, this is where Kamala gets it from."

As much as mother and daughter shared, Gopalan Harris believed the world would see them differently. Those who knew her say she was dismayed by racial inequality in the U.S. Understanding her girls would be seen as black despite their mixed heritage, she surrounded them with black role models and immersed them in black culture. They sang in the children's choir at a black church and regularly visited Rainbow Sign, a former Berkeley funeral home that was transformed into a vibrant black cultural center.

Though the senator talks of attending anti-apartheid protests in college and frames her life story as being in the same mold as her mother, she opted to pursue change by seeking a seat at the table.

"I knew part of making change was what I'd seen all my life, surrounded by adults shouting and marching and demanding justice from the outside. But I also knew there was an important role on the inside," she wrote in "The Truths We Hold."

To launch her political career, Harris had to unseat a man of her mother's generation — a liberal prosecutor who was the product of a left-wing family, who was active in the civil rights movement and who became a hero to other activists whom he defended in court. To win, Harris ran as a tougher-on-crime alternative.

Once in office, bound by the parameters of the law and the realities of politics, Harris' choices stirred some to dismiss her claims of progressivism even as many others fiercely defend her. She frames her philosophy in the example of her mother — concentrating on overarching goals through smaller daily steps.

"She wasn't fixated on that distant dream. She focused on the work right in front of her," the senator wrote.

Gopalan Harris defied generations of tradition by not returning to southern India after getting her doctorate, tossing aside expectations of an arranged marriage. Her daughter portrays her mother's spirit of activism as being in her blood. Gopalan Harris' mother took in victims of domestic abuse and educated women about contraception. Her father was active in India's independence movement and became a diplomat. The couple spent time living in Zambia after the end of British rule there, working to settle refugees.

Joe Gray, who was Gopalan Harris' boss after she returned from Canada to the Bay Area to work at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, struggles to describe how a 5-foot-1-inch woman managed to fill a room with her commanding presence.

Gray, now a professor at Oregon Health and Science University, didn't see Gopalan Harris as a "crusader in the workplace" but says she insisted on racial and gender equity, would make known her disapproval to an insensitive comment and was assertive in defending her work in cancer research.

Even from a distance, he's struck by how much Harris reminds him of her.

"I just get the TV persona, but a lot of Shyamala's directness and sense of social justice, those seem to come through," he says. "I sense the same spirit."

Lateefah Simon sensed it, too. She was a high school dropout-turned-MacArthur fellow Harris hired to join the San Francisco DA's office to head a program for first-time offenders. Simon was skeptical of taking a role in a criminal justice system she saw as broken and biased, but Harris impressed her, and soon she had a glimpse of her mother as well.

At campaign events, Simon would watch Gopalan Harris, always in the front row, always beaming with pride. She saw how both mother and daughter were meticulous about tiny details, how they were hard workers but maintained a sense of joy in the labors, how their laugh would echo in the room.

One time, Simon says Gopalan Harris sent her away from a fundraiser because she was wearing tennis shoes, gently reminding her, "We always show up excellent."

Years later, she heard echoes of the same message when Harris took a break from her Senate race to support her run for a seat on the Bay Area Rapid Transit District board. Descending from her campaign bus, Harris was quick with some words of advice for her friend: "Girl, clean your glasses."

"It's her saying, 'I believe in you and I want people to see what I see in you,'" Simon says. Remembering her brush with the senator's mother, Simon says: "If I got that from Shyamala just in that one moment, can you imagine the many jewels Kamala got from her growing up?"

It's an influence that far outweighed that of Harris' father. He and her mother separated when she was 5 before ultimately divorcing. She writes of seeing him on weekends and over summers after he became a professor at Stanford University.

In a piece he wrote for the Jamaica Global website, Harris says he never gave up his love for his daughters, and the senator trumpeted her father as a superhero in her children's book. But the iciness of their relationship was on display in February when she jokingly linked her use of marijuana to her Jamaican heritage. Her father labeled the comment a "travesty" and a shameful soiling of the family reputation "in the pursuit of identity politics."

The senator is curt in responding to questions about him, saying they have "off and on" contact and that she doesn't know if he'll have a role in her campaign. Labrie says though the father attended his daughter's Senate swearing-in, he wasn't at her campaign kickoff. He thinks the marijuana hubbub worsened their relationship. "I think that was the straw that really broke the camel's back," he says.

The singularity of her mother's role in her life made her death even harder for Harris. Gopalan Harris relished roles in her daughter's early campaigns but was gone before seeing her advance beyond a local office. The senator says she still thinks of her constantly.

"It can still get me choked up," she said in an interview. "It doesn't matter how many years have passed."

The senator still uses pots and wooden spoons of her mother and thinks of her when she is back home and able to cook. Her mother's amethyst ring sparkles from her hand. She finds herself asking her mother for advice or remembering one of her oft-repeated lines.

She pictures the pride her mother wore as she stood beside her when she was sworn in as district attorney. She remembers worrying about staying composed as she uttered her mother's name in her inaugural address as attorney general. She thinks of her mother asking a hospice nurse if her daughters would be OK as cancer drew her final day closer.

"There is no title or honor on earth I'll treasure more than to say I am Shyamala Gopalan Harris' daughter," she wrote. "That is the truth I hold dearest of all."

___

Sedensky can be reached at msedensky@ap.org and https://twitter.com/sedensky

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.