For decades, Florida has had one of the fastest growing populations in the country. In 2022 alone, it gained more than 400,000 new residents. After all, who wouldn’t want to live in the Sunshine State? Many come here hoping to trade cold, snowy winters for warm weather and sandy beaches, but it’s also become a refuge for those escaping more destructive weather events. In the second installment of our three-part series, Spectrum News anchor, Ybeth Bruzual, spoke to one such Floridian.

What You Need To Know

- Extreme weather events are prompting some to reconsider the safety of the place they call home

- Experts say as many as 6 to 13 million Americans could be forced to move as a result of sea level rise

- As extreme climate events become more frequent, is anywhere truly safe?

Krizia Lopez says she’s found happiness in Orlando.

“I‘m the kind of person that, I always write meditations. I believe in that, and write the things that you want to see in the future. And there [are] a lot of things that now are a reality,” said Lopez.

The life she’s built for herself here — friends she thinks of as family, a comfortable home and a fulfilling career — is one she always dreamed of. But it’s not where she thought she would find it. Before 2017, she always envisioned staying in her native Puerto Rico.

“I did not want to leave the island.”

“But now,” she said, “now, literally, I can breathe.”

Lopez was one of about 200,000 Puerto Ricans who uprooted their lives after Hurricane Maria swept through the island in 2017.

Years later, the memory of the storm is still fresh in Lopez’s mind.

“It feels like 24 hours, like ongoing.”

Not wanting to be alone, Lopez went to a friend’s home to wait out the storm. It’s a decision she now says she’s grateful she made. She still remembers the sound of the hurricane outside.

“The wind, the noise is like a ‘WHOOO.’ That noise.”

They spent the night bailing buckets of water out of the home. But the light of day illuminated the full scale of the surrounding destruction.

“Everything was blown apart and on the ground, all the trees, all the billboards, everything was on the ground. It’s like everything exploded,” said Lopez.

Lopez says the storm was like nothing she had experienced in a lifetime living in Puerto Rico.

She isn’t alone. Although no one extreme weather event can be attributed to climate change, scientists say storms like Maria are part of a pattern of increasingly severe storms triggered by rising global temperatures.

The models strongly suggest that hurricanes are going to be more intense in a warmer climate,” explained Tom Knutson, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

NOAA is a government agency that’s most commonly known for its weather forecasting through the National Weather Service, but it also studies future, long-term climate effects.

“Based on models, we expect the hurricanes are going to have more intense rainfall rates, because the atmosphere in a warmer climate is holding more water vapor typically,” said Knutson. “So these hurricanes act like sort of engines to converge water vapor in near the center of the storm, and it falls out in these fierce hurricane thunderstorms.”

Knutson’s work focuses on building and studying climate models.

“We’re using computers to sort of simulate the climate, the Earth’s climate system. And we do that to try to understand how the climate system ticks,” he explains.

These models use historical weather data to help scientists anticipate future climate trends through different lenses.

“The models themselves are a large set of equations that describe different parts of the climate system,” he said. “We have a set of equations that describe the atmosphere and the ocean and the ice sheets and the land surface.”

But all these changes are interconnected. Knutson and his colleagues are also studying models that can help predict how changes to one climate system can affect another.

Knutson cautioned the models are not crystal balls, but observational data has proved that they are highly effective at predicting certain climate impacts.

“We have a very high confidence that we’re going to continue warming being driven by this increase in greenhouse gases,” he said.

Rising temperatures have different effects on communities across the country.

“Another thing we’re seeing very clearly is the increase of extreme precipitation in many parts of the U.S. It seems to be strongest in the northeast and sort of north central part of the U.S.” said Knutson. “Now if we look in a different part of the U.S., to the southwest, part of the U.S. and the Colorado River basin, those are areas where we’re seeing more evidence in the past data for increases in drought risk.”

Globally, the effects could be even more severe — in some places, models suggest heat stress could reach a boiling point.

“There’s been some papers out on that which suggest that with very large future warming scenarios, that parts significant parts of these areas of the world which are presently warm and humid, could approach these basically uninhabitable levels in terms of heat stress,” he said.

Knutson says those heat extremes are most likely to affect regions of India and the Middle East. While areas like the Mediterranean and Southwest Africa show indications of increasing drought risk, and sea level rise encroaches on coastal communities across the globe.

“I think,” said Knutson, “that some type of effect is occurring practically everywhere.”

Many places are already beginning to experience these changes, with the most dramatic effects occurring in communities without the resources to adapt and recover from changing weather patterns.

Lopez said, "the hurricane, it was the like the el punto. Ok, ya no puedo mas."

She said for her, it was the tipping point.

The decision to leave, Lopez said, was about more than just the hurricane. Even without severe weather, power outages were a regular occurrence, and the island’s economy had long been struggling. Despite a college degree and a coveted job with a San Juan radio station, she said it was a challenge to make ends meet.

“The income, it was not good at all because I’m a millennial, and as a millennial, when we graduated, we didn’t we didn’t have the opportunity to see a prosperity on the island, abundance,” remembered Lopez.

She described the hurricane as the straw that broke the camel’s back. In the weeks that followed, Lopez says she felt lost. She had no electricity or running water and access to food and other basic supplies was limited. Without work, she didn’t know how she would make rent. Worst of all, she said, was the lack of phone or internet service.

“You didn’t know if your family were alive or no,” she recalled.

When she finally got phone service, the first call that came through was one that would change her life.

“[My best friend] called me and she [was] like, Krizia, now is the time. What are you waiting for? [What more do you have to think about]? Move.”

Her friend offered her a place to stay while she got back on her feet — but that place was in Orlando, Florida.

Lopez took it as a sign.

“I remember I received a $500 voucher. And with that, I bought my airplane ticket to get here.“

Lopez’s story mirrors that of many people who migrate after a climate event.

“We know that people are most likely going to move to places where they already have friends and family or connections to a given area,” explained Florida State University Sociology professor Dr. Mathew Hauer.

Hauer has spent his career studying human migration patterns and is looking ahead to what may be the country’s next big demographic shift.

“We’re already seeing people murmuring about sort of associated impacts around hurricanes, around flooding.”

Changes like these, he said, are prompting people to start thinking about where they’ll want to live in the future.

Much of his work has been focused on just one facet of climate change — rising sea levels. Even excluding other climate effects, like heat, drought and severe storms, Hauer estimates between six and 13 million people in the U.S. could end up moving because of sea level rise.

“We’re still looking at a magnitude of migration that is on par with the Great Migration,” he said.

But that number only accounts for those directly affected by rising sea levels. Hauer explained there are larger ripple effects as coastal communities shrink, and demand for services goes down.

“You’ll need fewer dentists, construction workers, bartenders, baristas, traffic cops and so on in the place where they originated from.”

Factoring in this secondary wave of migration, Hauer says the true impact of sea level rise on the U.S. population could far exceed 13 million people.

A migration event of this scale, he said, demands preparation now.

“What keeps me up at night is we’re not going to do anything, that we end up with this sort of apathetic response where we wake up one day and we go, ‘Wow, we should have done something 20 years ago. ‘“

Anne Junod, a senior researcher at the Urban Institute, is trying to avoid just that. Her research focuses on recommendations for cities that are likely destinations for climate migrants.

“These potential receiving communities need the data, the evidence to help understand what impacts they could be facing to their communities and their institutions and how they can prepare.”

Preparing for the future, she said, starts with knowing where people are likely to go. While emerging evidence suggests some people move far across the country, Junod said most are far more likely to make small moves.

“We know that, at least at this stage in climate change, we’re seeing people move a lot more within kind of regions.”

That puts cities like Orlando, on the front lines of climate migration.

Dr. Fernando Rivera, who runs the Puerto Rico Research Hub and the University of Central Florida, has witnessed that migration firsthand.

“There was the mass movement of people from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria.”

Rivera partnered with Urban Institute for the Orlando arm of the study — examining the city’s response to the influx of migrants and identifying areas for improvement.

“We interview people in terms of what’s the reception from different agencies and groups that were in charge of five areas, right? So employment, financial services, health, cultural, social activities and housing.”

Overall, he said, Orlando did well, and was able to meet the needs of incoming migrants.

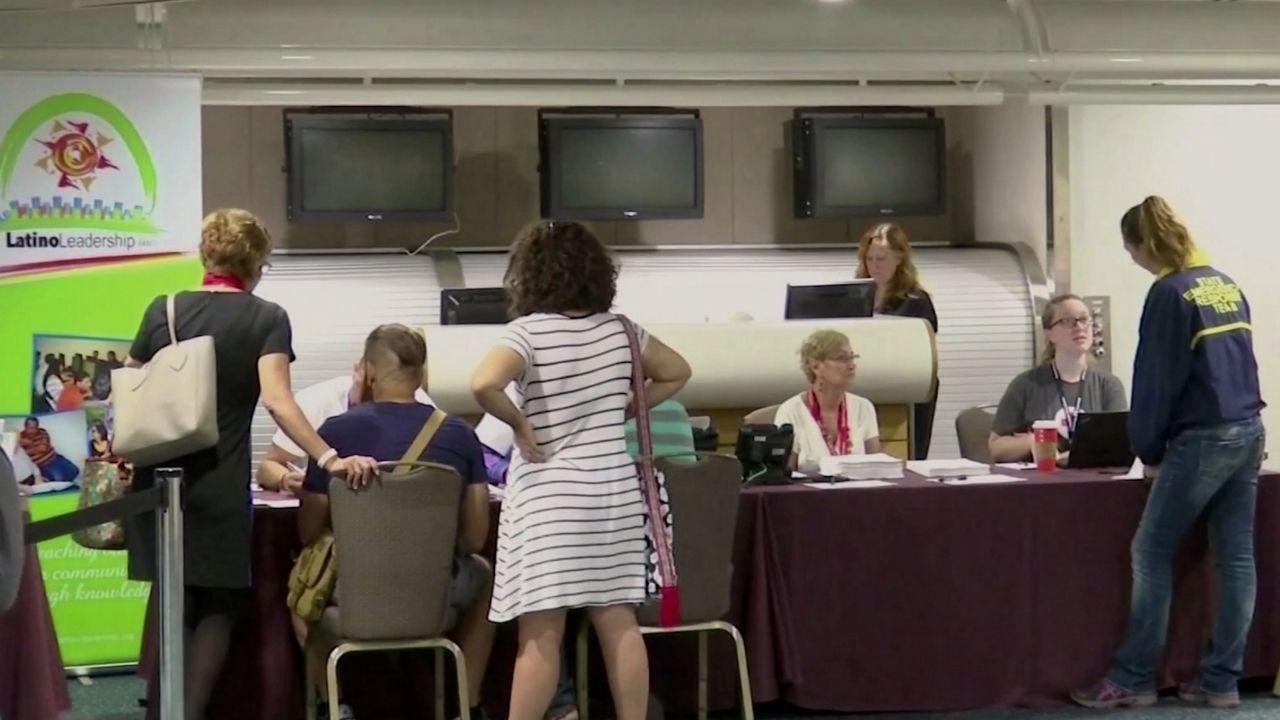

“The level of support that it was experiencing here, you know, it was the assistance center at the airport. And you could come here, and you could get like a bus pass, you could get your license, you could get a job, you could get health insurance,” said Rivera.

But he worries about the city’s ability to handle similar events in the future.

“The issue of housing nowadays, you know, the issue with insurance, all those types of things, that’s a problem that continues to worsen in the area. I’m not sure we’ll be able to absorb that the way we did in 2017.”

Much of the 2017 success, he attributes to an outpouring of support from Orlando’s large Puerto Rican community and other Latino groups in the area.

“It was, it was overwhelming the amount of help that I think every Puerto Rican leader here, everybody was trying to help, right? Everybody was trying to do something from the faith level to the faith sector, to the nonprofit groups, to the governmental groups, to the educational groups. Everybody was trying to do something.”

But Rivera said reliance on private organizations is not a permanent solution. Many of the groups that provided aid in 2017 aren’t around anymore.

“The government cannot rely on the good heart of other organizations.”

And perhaps the biggest challenge for future climate migrants to Central Florida may actually be the climate itself.

Spectrum News severe weather expert Maureen McCann said she was shocked when she looked at the forecast for Hurricane Ian in September of 2022.

“We had these bands of rain training over the same areas, these highly productive downpours, you know, these rainfall rates that were bringing colors onto our graphics that we never see.”

McCann said Hurricane Ian was unlike anything she’s experienced in a decade of covering Florida’s storms.

“The projection of what the rainfall totals may look like, 8 to 16 inches, I mean, that’s more like a snowfall map that you see in the northeast.”

Compared to other Florida cities like Miami or Tampa, Orlando is relatively far inland — historically, that meant the city was safe from the more extreme impacts of hurricanes. But climate change is changing that.

“When you have warmer temperatures in the air, that leads to a greater capacity to hold water vapor.”

McCann said events like this could become more common as the climate continues to warm.

“The science indicates that there may be an increase in major hurricanes. While the frequency of hurricanes or the number of storms may not go up, the intensity will, because of the amount of water vapor that’s present in a warmer environment,” she explained. “We see that when storms get really close to the coast and they encounter these warmer sea surface temperatures, and they get stronger.”

While many of the effects of climate change may be inevitable, Rivera believes the disasters they cause don’t have to be.

“Hazards we’re going to have right? Here again, snow, storms, rain, all the stuff of things. The disaster happens when we, as a society decide not to prepare.”

For Orlando, he said, that means updating city infrastructure to better withstand the next storm, and rethinking how we build back in vulnerable areas.

“You have to be ready,” he insisted. “You have to be proactive.”

It also means looking ahead at how the city can provide for current residents and those who come here seeking safety in the future.

“This is not going to go away. I wish we could. I wish it got colder, we don’t have any more natural hazards happening. But that’s not the reality, and I think we are at the point that we’re seeing it every day.”

The threat of more intense weather here in her new home is a scary thought for Lopez, who is still dealing with the trauma of Hurricane Maria. During a recent storm, her home lost power, spoiling the food in her refrigerator.

"It takes me to the to the hurricane because of that smell. And I remember that, I began to cry.” The smell, she explained, was all too familiar. “I remember [having] to live with that smell, I don’t know for how long until I moved here.”

Still, Orlando is her home now, and she plans to stay here.

“I came here because of a trauma, but still, a lot of the things that I wanted, now, now I have them.”

Here, she said, she finds comfort in having a large Puerto Rican community around her. It offers her a reminder of the culture she loves, but with a sense of safety and security that she never had on the island.

But when it comes to long-term planning, even cities like Orlando may become less attractive. As the effects of the changing climate intensify, where will people go next? The search for that answer may lead to some unexpected places.