The Erie County Holding Center and the Erie County Department of Forensic Mental Health implemented a series of changes to adapt to their changing population in the decade since the Department of Justice took on the oversight of the facilities.

That oversight proved beneficial for both departments, giving them the federal backing to secure much-needed funding and resources while developing best practices to better serve the increase of mental health and substance use issues under their care.

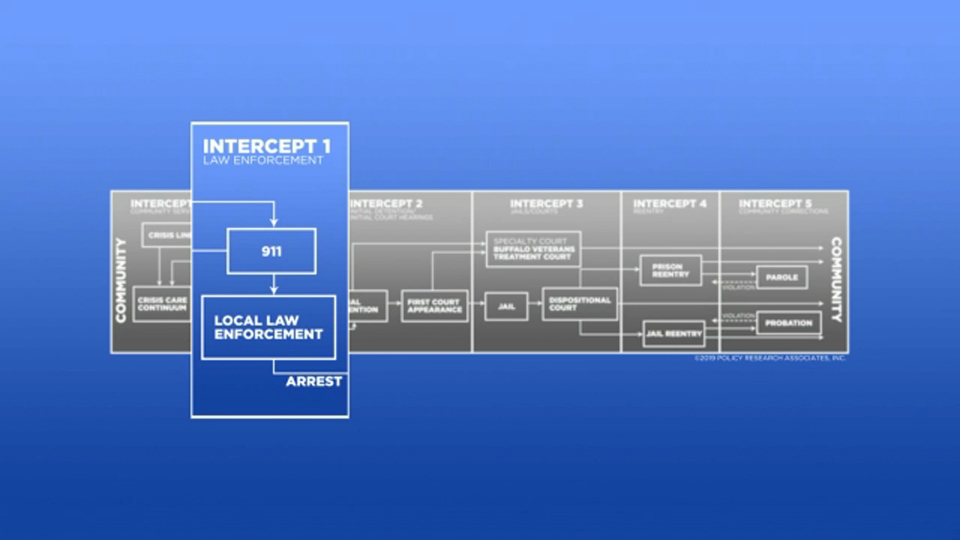

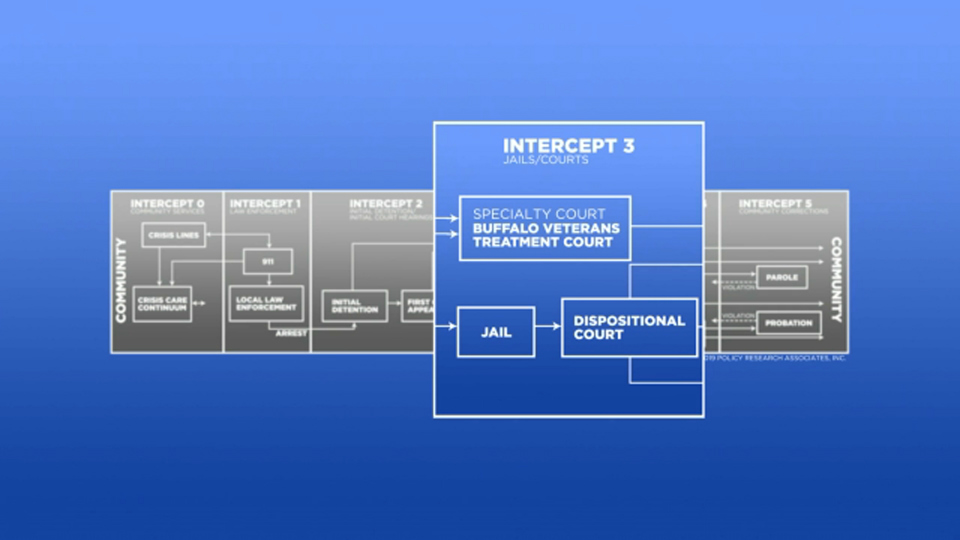

"Think of the criminal justice system as something where there are multiple points where interventions can occur," said Michael Ranney, former Erie County Commissioner of Mental Health. “It's called the sequential intercept model.”

That model is based on best practices by The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and is designed to help people struggling with these things from their first interaction with police until they exit the system.

The changes started with having officers participate in crisis intervention training or CIT.

“We were actually the first corrections based CIT program in New York State,” said Thomas Diina, the superintendent of Erie County Holding Center.

That training stemmed from a partnership outside the holding center with the Cheektowaga Police Department in April 2013 through the nonprofit Crisis Services, according to Tracie Bussi, the director of emergency mental health response services at Crisis Services.

Six years ago the Cheektowaga Police Department recognized that their police academy didn’t adequately train officers for the mental health calls they were receiving daily, according to Bussi.

Now, the nonprofit trains law enforcement in places like Grand Island, Buffalo, City of Tonawanda, Lackawanna and West Seneca in addition to training done at ECMC and Canisius College.

In early December, they trained an additional 22 officers bringing to 577 the total of trained officers in Erie County, according to Bussi.

The Erie County Holding Center is looking to add another week of mandatory crisis intervention training to their Basic Corrections Academy, Diina said.

In addition to CIT, the holding center also trains its officers in de-escalation, suicidality, and withdrawal symptoms and developing treatment plans.

The sheriff's office meets weekly with the Erie County Department of Forensic Mental Health, which provides mental health and substance use treatment at the jail, to set up treatment plans for inmates that are battling severe, persistent mental illness, said Jennifer Howell, an Erie County Holding Center Sergeant.

In addition to the partnerships with the county and Crisis Services, the holding center also partners Buffalo's Veterans Treatment Court, which is the first of its kind in the nation and is used as a model in 461 different municipalities.

That court was founded by Buffalo City Court Judge Robert Russell to address underlying mental health issues for veterans like PTSD or Substance Use Disorders.

"All of our veterans are housed in one specific post within the jail,” Diina said. “The Veteran Services can come in and provide programming right on the housing area."

Housing this population together helps them rely on a shared experience of being in the military, he said.

But that's not the only innovative practice happening in the jail,

In the fall, it partnered with the nonprofit Peaceprints of WNY to launch a re-entry pod after it received a $1 million grant from the Second Chance Act to address recidivism rates at the local level.

The funds will be used to address reentry services and programs for inmates with mental illness or substance use disorders. Identified inmates nearing their release will be directed to community partners to receive transitional services.

Cindi McEachon, the executive director of Peaceprints of WNY, said this population has long been under served, citing that 81 percent of people booked into county corrections have had previous involvement with the local jail system.

Peaceprints of WNY has its own jail pod for this program called Project Blue, which will provide comprehensive reentry services to this population.

"Step one is to go through this cognitive behavioral therapy training and go through the workshop with us and then you're going to go right on to a transitional workgroup where you're getting paid every day,” McEachon said. “And then we're also getting you connected with community-based employment."

Outside of the jail, the Department of Forensic Mental Health Services is in the final stages of finishing its one-stop-service linkage for those exiting the jail after realizing that transportation and time are major barriers to accessing services.

"When they leave here, they have difficulty getting their needs met, re-adjusting to society, finding employment, getting housing, food, transportation,” Howell said of these partnerships. “I think that in connecting people with resources on the outside, that it will hopefully greatly reduce the recidivism rate."

However, the holding center maintains that while they should help provide these services, they shouldn’t be the main service provider in the community.

"I think we are a good intercept point to start linking people to services, but we should be a last resort,” Diina said. “It shouldn't be automatic that they get incarcerated because of some conduct resulting in part from a mental health issue."

Possible Solutions:

The holding center can continue the partnership with different community agencies like the courts, Department of Forensic Mental Health and non-profits.

Outside community organizations can improve access to housing, food, transportation and other social determinants of health for vulnerable populations in rural communities and in zip codes that have higher representation at the holding center, as discussed in this story.

The next story in the “Navigating The System” series tackles how different agencies are working towards bridging the communication gaps. You can watch that tomorrow at 6 and 11 p.m.