Dr. Andrea Littleton spends two days a week walking through the South Bronx, providing care and outreach to people living on the streets.

She’s been doing this work for about 15 years, but a little more than a year ago, she noticed a few changes among her clients.

Drug users began exhibiting necrotic lesions that were different from the type of ulcerations Littleton typically sees. These lesions were often on areas of the body away from the site of injection.

She also noticed that people were responding less to naloxone in cases of overdose — or required more doses than they’d usually need.

Health officials say both of these trends are indicators of xylazine use, a veterinary drug that has been making its way into the illicit drug supply in the United States. Littleton is among those raising the alarm about the drug’s growing presence in New York City.

“I do suspect that, unfortunately, we're going to be seeing a lot more of this,” said Littleton, who manages the homeless outreach teams in partnership with Care for the Homeless, a direct services organization.

The introduction of xylazine into the illegal drug supply chain comes as the city battles a record number of overdose deaths since it began tracking the number two decades ago.

In 2021, 19% of opioid-involved overdose deaths included xylazine, according to the city’s Department of Mental Health and Hygiene. That number has since increased, according to law enforcement officials, though there is no recent data publicly available beyond 2021.

While it’s still unclear how quickly this issue is growing because the data is still new, observations from experts, and from people on the ground, warn that this is becoming a growing concern.

“It's not true in every part of the city, but generally speaking, we certainly are seeing an increase,” Bridget Brennan, special narcotics prosecutor for New York City, said.

She said her team is focused on areas where xylazine use is known to be more concentrated, including neighborhoods in Staten Island and the Bronx.

“We're seeing [increases] across every borough—we're certainly seeing it in Manhattan and Queens as well—but it's not uniform across the borough,” Brennan said.

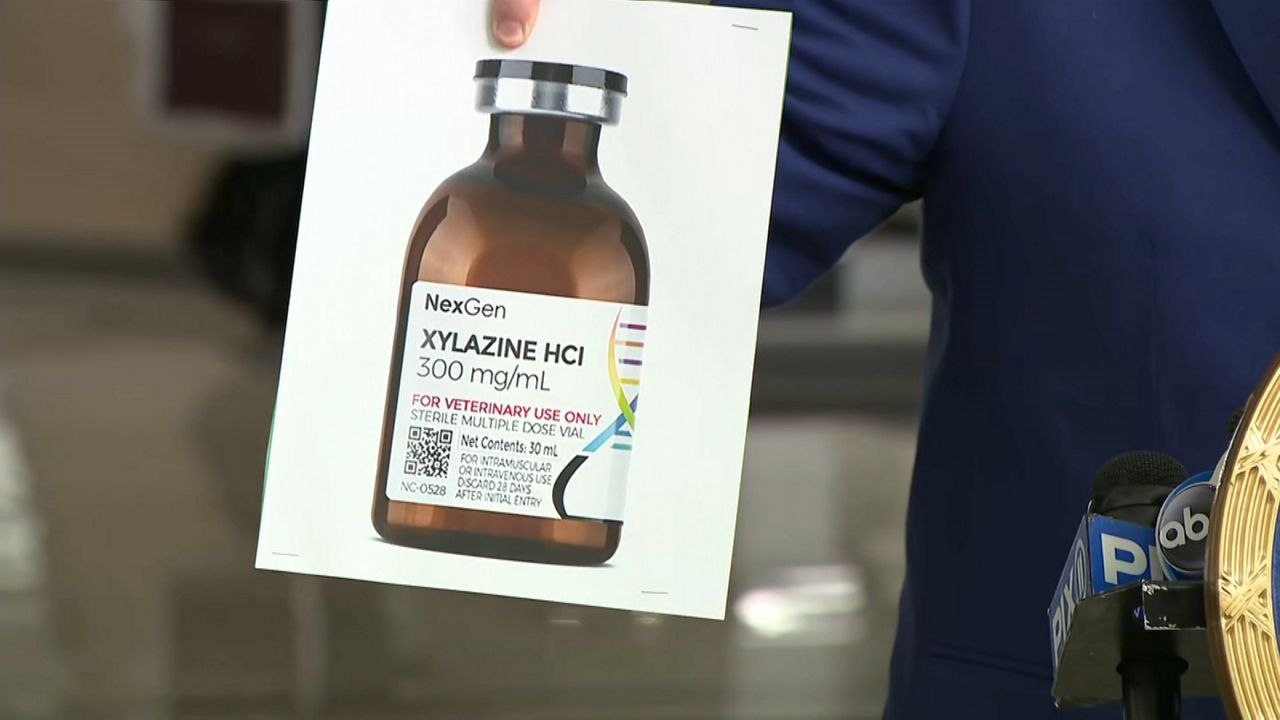

Xylazine is a central nervous system depressant that slows a person’s breathing and heart rate and lowers blood pressure. It’s a powerful tranquilizer approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in animals like horses as a veterinarian-prescribed analgesic.

“This is actually being diverted from the veterinary drug supply because it is not a human medication. It is a veterinary medication, so it's not a controlled substance and it can be purchased on the internet,” Ramsey said.

The city started taking notice of xylazine in the drug supply as far back as 2021, Brennan said.

It’s often mixed with fentanyl, a highly potent opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine.

The two drugs combined, fentanyl and xylazine, can make resuscitating someone in the case of an overdose more challenging.

“They act as suppressants on the body — they suppress heart rate, breathing and all that — but Narcan is effective in reversing an overdose from fentanyl, but it's not effective on xylazine,” Brennan said.

Officials report that drug dealers are likely mixing it into their supply to not only cut costs, but also because it may prolong the high for someone using fentanyl, which moves through the body quickly.

“That high is going to peak, or it may knock them out very quickly, and I think the sell with xylazine is that because it's a sedative, it slows down the impact of reaching that high,” Brennan said.

Data collection, whether through autopsies or drug-checking, have only recently become routine in the city.

Last month, Sen. Chuck Schumer called on the Drug Enforcement Administration to send a team to New York to help address the problem.

“It’s a deadly, skin-rotting zombie drug that evil drug dealers are now mixing with fentanyl, with heroin, and with other drugs,” Schumer said.

“It’s already bringing a horrific wave of death and overdose to upstate New York, and it’s on its way to New York City and Long Island, where we've already seen it begin to rear its ugly head,” he added.

Schumer said a DEA team would include special agents, investigators, chemists and pharmacologists, and would focus on diverting the drug as it crosses between legal and illegal use.

“The diversion teams are to drugs like our Navy SEALs teams are to national security,” he said.

But Dr. Kelly Ramsey, chief of medical services at the state’s Office of Addiction Services and Supports, cautions against panic for fear that it could lead to blowback against a vulnerable community.

“When we instill panic, we help create myths about substances, and it also can increase stigma towards people who use substances,” said Ramsey, who encourages a comprehensive approach to overdoses, instead of just relying on naloxone.

“It's more important to think about polysubstance abuse as being the norm and polysubstance overdose as being the norm, so that we react appropriately,” she said.

It’s something that Sam Rivera, executive director of OnPoint NYC, which runs the two overdose prevention centers in the city, advocates as well.

“We don't want to create this fear,” Rivera said. “We know most people do. We don't work from that place and with that energy.”

One tactic that he said has been helpful is working closely with service providers in Philadelphia, which has been particularly hard hit by xylazine.

In 2021, xylazine was found in over 90% of drug samples tested in Philadelphia, according to Substance Use Philly, a division of the city’s health department.

Rivera said OnPoint has been collecting samples of xylazine from Philadelphia and doing research to ensure that their team is prepared to deal with a sudden increased presence of the drug, including how to best react to cases of overdose.

“We have an oxygen protocol already in place so we have that much of an advantage to respond to an overdose where we're able to utilize oxygen right away,” Rivera said. “We know that naloxone or Narcan isn't going to respond to [xylazine] because it responds to an opioid, but the oxygen definitely helps.”

Testing strips for xylazine, like the kind available for fentanyl, are not publicly available yet. Drugs can be tested using a spectrometer for a range of substances, including fentanyl and xylazine, at two of the city’s overdose prevention sites, which are in East Harlem and Washington Heights.

Ramsey is hopeful that these strips will become more widely available in the near future.

“That will help because that'll give people a qualitative answer of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ whether xylazine is in their substance,” Ramsey said.

Littleton, of Care for the Homeless and BronxWorks, said clients are becoming more aware of the drug and are expressing a desire to be able to test for it.

She said that unlike fentanyl, which some clients may prefer to have in their supply, they seem to be wanting to test for xylazine to avoid using this substance.

“They are familiar with the lesions that people get from it, and they're scared of that,” Littleton said.