A row of boats waits at the ready, lined up as evenly as they can be given the choppy water— still rippling from the wake of the boats that ran the course just minutes earlier. The starting boat’s Jolly Roger snaps in the wind. Heather Strout Thompson takes her place at the wheel of her boat, Gold Digger, and braces for acceleration.

“When I hear you say ‘go,’ I’m going!” Thompson shouts over the rumble of idling engines.

Her stern man nods, eyeing the starting flag with unblinking focus.

.gif)

In an instant, the flag comes down. At his signal, Thompson leans on the throttle, and Gold Digger’s engine roars to life.

On dry land, 40 mph doesn’t sound like much, but out on the water, speed works differently. Slicing through waves with the wind howling in your ears, and the wash from other boats coming over the sides, 40 mph feels more like 80.

For a lobster boat like Gold Digger, that kind of speed can easily blow out an engine. It’s a crisis that befell one boat already this morning, and a big risk for racers like Thompson, whose livelihoods depend on their boats.

“I haul eight hundred traps out of that boat,” says Thompson. “It's not just for play.”

But if she’s holding back on the race course, it doesn’t show as she pulls ahead of the competition and cruises towards the finish line.

In seconds, the race is over. Thompson remains undefeated in her racing class.

“I was addicted from the first race,” she says. “I was nervous. I was excited. It's adrenaline. And that's what you get addicted to as a racer.”

Thompson's first race was three years ago, but her love of lobster boat racing started much earlier. She remembers going with her dad to watch the races as a kid. “We’d watch all these fast boats go, and as a little girl, sitting there watching all these boats, I'm like, ‘someday I want to be able to do this.’”

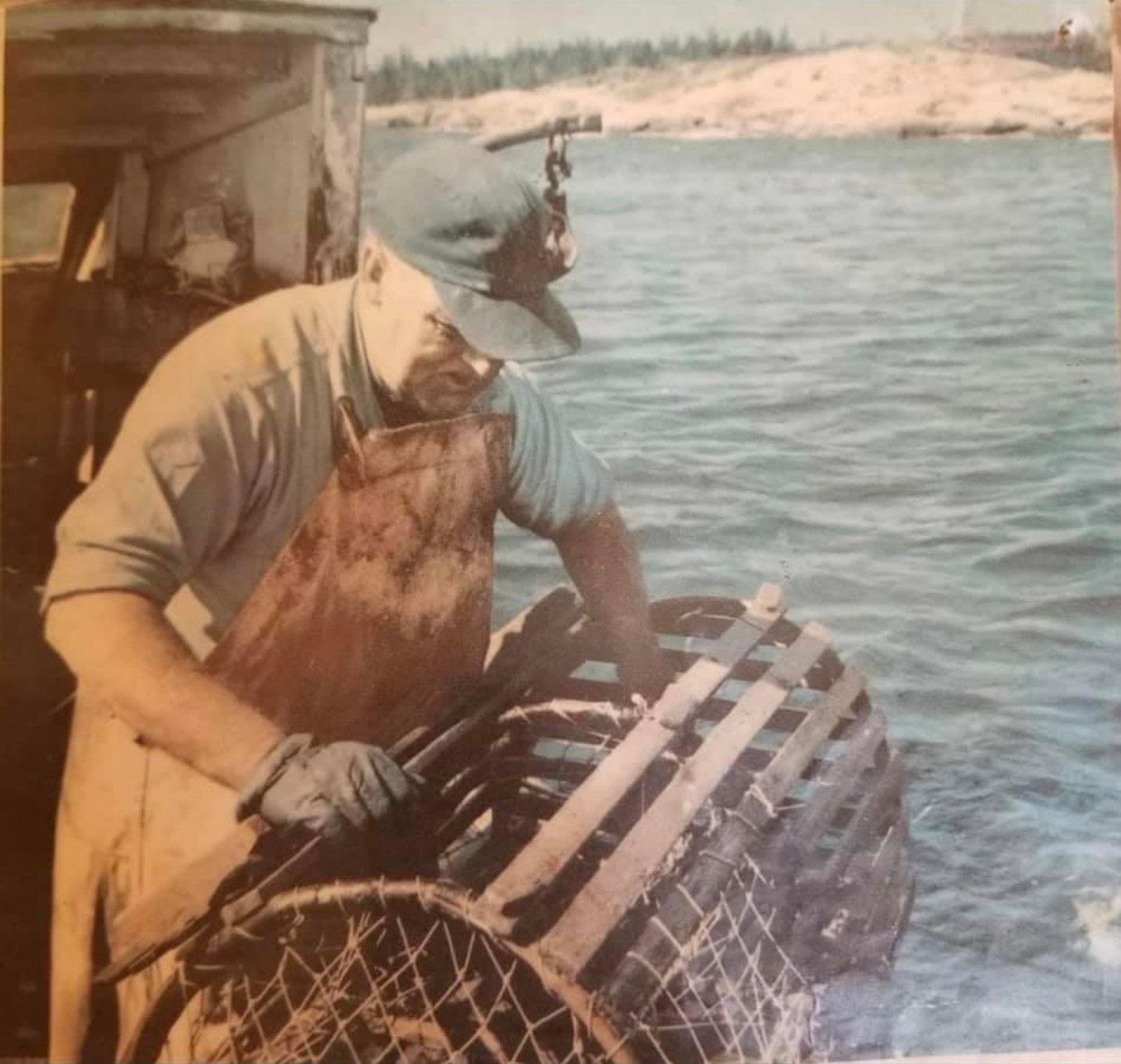

Her father, she says, is the reason she became a lobster fisherman. “I started out when I was 10 years old on his boat, which ended up being my first boat.”

Thompson remembers long days working as her father’s stern man.“He pushed. He was hard,” Thompson says. “I respect it now.”

Lobstering is a family tradition — one that Thomspon has also passed down to her two sons. “My kids used to go with me, they'd go, they'd lay on the bulkhead and nap,” she remembers. Both boys now have lobster boats of their own, making them fifth generation lobstermen.

For Thompson, lobstering is all she’s ever known. Still, she says, it’s no easy job. “You've got to have some tenacity. You've got to be able to push, not give up, because it's not easy.”

It’s that same mentality that keeps her coming back to the races. “I don't want to be better than anybody else, but I want to be the best I can be,” says Thompson.

She admits though, that when it comes to racing, she still plays to win. “I’m not going down without a fight, that’s for sure.”

As one of only a few women in the sport, Thompson says she feels her record has won her the respect of her male opponents. Out on the water, speed and skill are all that matters.

“I always say, ‘it's always sweet to be able to beat a man.’ But for me, I don't look at them as men out there racing against me. You know, I'd want to beat a woman,” she says. “I just want to win.”

Still, she does want to see more women racing in the future, and hopes to do her part to inspire the next generation.

As another race approaches, Thompson picks up an extra passenger — a young girl, eager to experience the rush of a lobster boat race up close. The girl takes her place beside Thompson, adjusting her neon orange sunglasses as they slip down the bridge of her nose.

Thompson leans over. “Are you excited, or nervous, or scared?” she asks.

“All of them,” the girl smiles.

“That's adrenaline,” Thompson tells her. “It feels good, doesn't it?