LEXINGTON, Ky. – Nearly 90,000 Kentuckians are still waiting on COVID-related unemployment benefits and more than 500 have been waiting since the pandemic began. Outdated software used to operate the state’s unemployment insurance website and subsequent upgrades that created glitches are just some of the problems creating the backlog.

What You Need To Know

- State passed on $90 million of federal funds to upgrade system

- Technology and overall process need streamlined, experts say

- KYCEP director says there are too many restrictions

- Policy analyst claims Kentucky could learn from other states' mistakes

Jason Bailey, executive director of the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy (KYCEP), said aside from the archaic website and operating software, Kentucky’s outdated eligibility rules and inadequate agency staffing have kept people from qualifying for assistance and delayed benefits to others.

Even with the claim-filing problems, more than 1.2 million Kentuckians have received nearly $1.4 billion from the state’s unemployment insurance program and an additional $3.5 billion in emergency, extended, and supplemental benefits provided by the federal government.

“The seeds of Kentucky’s unemployment system problems were planted through past state policy decisions and a failure to make needed investments over decades,” Bailey said. “To prevent similar challenges in the future, the Kentucky General Assembly must modernize the state’s system to improve access to benefits through measures that have worked in other states. Legislators should also protect the system from attempts to further reduce supports for laid-off Kentuckians – as have been proposed in recent sessions of the General Assembly. The problems the state has faced in providing UI were avoidable and will recur in future recessions unless Kentucky makes needed improvements and avoids harmful new cuts.”

An article by Jared Bennett of the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting (KCIR) details how Kentucky was one of 10 states that passed on receiving federal money in 2009 set aside to modernize unemployment systems across the country. Michele Evermore, a policy analyst with the National Employment Law Project, said the $90 million that would have been allocated to the commonwealth was not accepted because of stipulations tied to the funds.

“To get that modernization money, you had to do improvements to your system – you had to fix it, not just not just use it for computer upgrades,” Evermore said. “You also had to do some other things and many states didn't take the money because they didn't want to do the big system improvements outside of technology. Many states that upgraded their IT systems didn’t do the other system improvements. There were a ton of stories about how everything totally failed in Florida, and that was a modernized system. Louisiana did poorly. Michigan's system, after they upgraded it, there was some sort of blackbox algorithm that falsely flagged 60,000 people for fraud, and that was right after they increased the penalty for fraud to four times the amount paid, plus 12% interest. I wouldn't necessarily say the answer is always spending a lot of money on the computer system, although taking money to fix your computers is generally a good idea.”

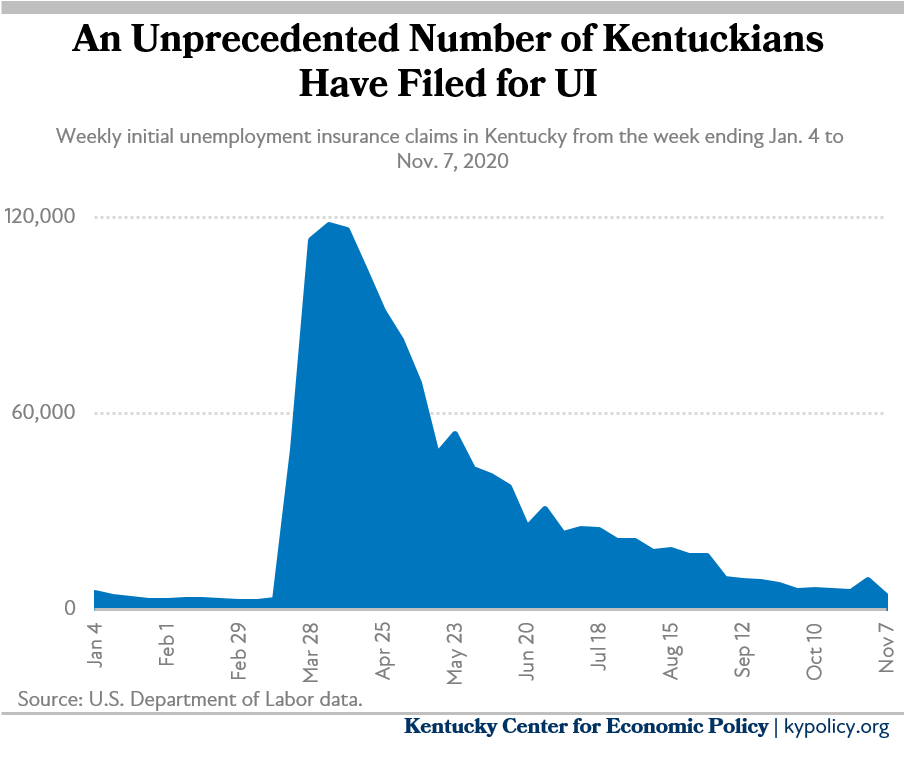

Beginning in March 2020, more than 326,000 Kentucky nonfarm jobs were lost in two months, and many self-employed workers lost their livelihoods as well, resulting in a massive and unprecedented swell in unemployment claims. Over the course of several months beginning in late March, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians filed claims and while new claims have recently receded, real unemployment remains at or exceeding the highest level since the Great Recession.

“In addition to protecting the state from more job losses with its counter-cyclical effect, unemployment insurance has been critical to helping laid-off Kentuckians get by, including workers who are disproportionately low-wage,” Bailey said. “Those households have far less wealth to fall back on compared to workers with higher incomes, and Black workers have less household wealth on average, yet have also been disproportionately laid off on average in this crisis. Unemployment insurance is an important tool to mitigate growing poverty and inequality in the COVID-19 recession.”

Bailey said Kentucky has limited access to benefits for several reasons, including eligibility being determined based on earned income, which excludes many part-time, temporary, and low-wage workers, as well as recent entrants into the labor force.

“These exclusions fail to reflect the modern economy,” Bailey said. “More employers are relying on temporary and part-time workers, and more workers must patch together a variety of gigs to support themselves due to a lack of full-time employment opportunities and because they are in school or have caregiving responsibilities.”

Unlike a number of other states, Kentucky doesn’t allow benefits for separations due to reasons outside the workplace, such as the need to quit due to domestic abuse, compelling family reasons such as an illness or disability, or the need to relocate with a spouse. Kentucky also denies benefits to people who are seeking part-time work and workers who need access to training, Bailey said.

Also unlike many states, Kentucky doesn’t allow “work-sharing,” which are benefits being used by companies to reduce hours across the workforce while keeping people employed and supplementing a portion of their lost wages with unemployment benefits.

In addition to difficulties in qualifying for benefits and inadequate benefit amounts, as part of cost-saving measures in 2017, employees providing in-person assistance to workers filing claims were pulled from 31 centers across Kentucky and concentrated in fewer regional hubs, limiting access to assistance and making it more difficult for Kentuckians without dependable internet access to file a claim. In 2019, 16.6% of Kentucky households did not have access to the internet at home, according to Census data.

“The enormous crush of claims due to the COVID-19 crisis and the state’s antiquated computer systems also make benefits more difficult to access,” Bailey said. “The online interface that Kentuckians use to file unemployment claims is approximately 20 years old, and the technology infrastructure used to collect employer taxes, calculate eligibility, and determine benefit amounts is nearly 50 years old, running on an outdated and inflexible programming language called COBOL. A funding mechanism was set up in 2018 to accumulate $60 million to update that part of the system with modern software.” The state began seeking vendors to replace the system in March of 2020.

Bailey said the Kentucky General Assembly should take several steps to better prepare for the next recession, such as adopting an “Alternative Base Period” (ABP), which is the past three completed calendar quarters and the period of time between the last completed quarter and the effective date of an unemployment claim. The ABP, which one of the stipulations tied to the $90 million of federal money, may only be used if one does not meet the minimum eligibility requirements using the primary base period.

Another step, Bailey said, is broadening the “good-cause” definition for leaving employment; just 19% of unemployed people in Kentucky were covered by unemployment insurance because the rest had exhausted their benefits, left the workforce, or worked a part-time or contract job that did not qualify, according to the KCIR article.

“Kentucky’s law on good cause reasons for separation is vague and only specifies ‘lack of work’ as a concrete example of good cause that could qualify someone for unemployment insurance benefits,” Bailey said. "As mentioned before, in practice, only a set of reasons narrowly related to the job – lack of work, employment-based harassment, etc.– are considered good cause. The state should broaden this definition to include other compelling reasons for needing to leave a job, regardless of whether the reason is due to conditions specific to the job. For example, good cause could include an individual voluntarily leaving a job to flee a domestic violence situation, following a spouse who must relocate for work or because they must care for a sick loved one long-term or because they have become sick themselves. After the Great Recession, when the federal government provided incentives to states to modernize their unemployment insurance programs, 32 states adopted at least one of these good causes for separation.”

Bailey also suggested the General Assembly implement a work-sharing program that could decrease layoffs by giving employers an avenue to reduce employee hours with pro-rated unemployment insurance benefits helping to make up the difference for the lost hours rather than laying off employees. He also suggested developing an updated and improved benefit application process, re-establishing in-person application assistance when it is safe to do so, making inadequate benefits amounts more reasonable, especially at the bottom and for those with dependents, and allowing part-time workers to receive benefits while seeking part-time work.

When Gov. Andy Beshear began taking steps this past January to replace the outdated technology, the state was still using a program that predates the personal computer when the coronavirus ushered in a new employment crisis.

“I know Gov. Beshear has put about $6 million toward sort of tweaking the existing computer system to try to make some improvements as they can on the fly,” Bailey said. “Every state has been somewhat overwhelmed, but we're one of the worst for the delays and denials people have been given. To operate the way other states operate — would require a lot more money and more time — I think the governor is likely to ask for some more money for that in his budget.”

Evermore said the modernization worked well in some states, such as Washington, but in most states, the new system worked poorly.

“I think that the best thing to do in a place like Kentucky that was sort of starting to look at modernizing and has spent some money on it, is to look at the better and best practices are coming out,” she said. “Now is a pretty good time to really, really modernize because we know a lot more from the mistakes of other states.”