CINCINNATI — Jacqueline Hernandez said she wanted to be a nurse when she gets older, but she fears language barriers and other challenges she faces don’t make that realistic career pathway for her.

The 17-year-old speaks Spanish as her primary language.

For that reason, the Aiken High School Senior signed up for the Entrepreneurship Mentoring Program. The initiative through Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS) aims to help immigrant, refugee and non-English speakers in the district learn important life skills and prepare them for starting their own business or expanding one that’s family run.

What You Need To Know

- The Entrepreneurship Mentoring Program provides resources for immigrant and refugee students in Cincinnati Public Schools

- The program goal is to help students overcome barriers such as language and immigration status

- The pilot has 55 students, from four high schools, this year, but there are plans to expand in the future

- Topics include things like how to get a small business loan and setting up an Employer Identification Number

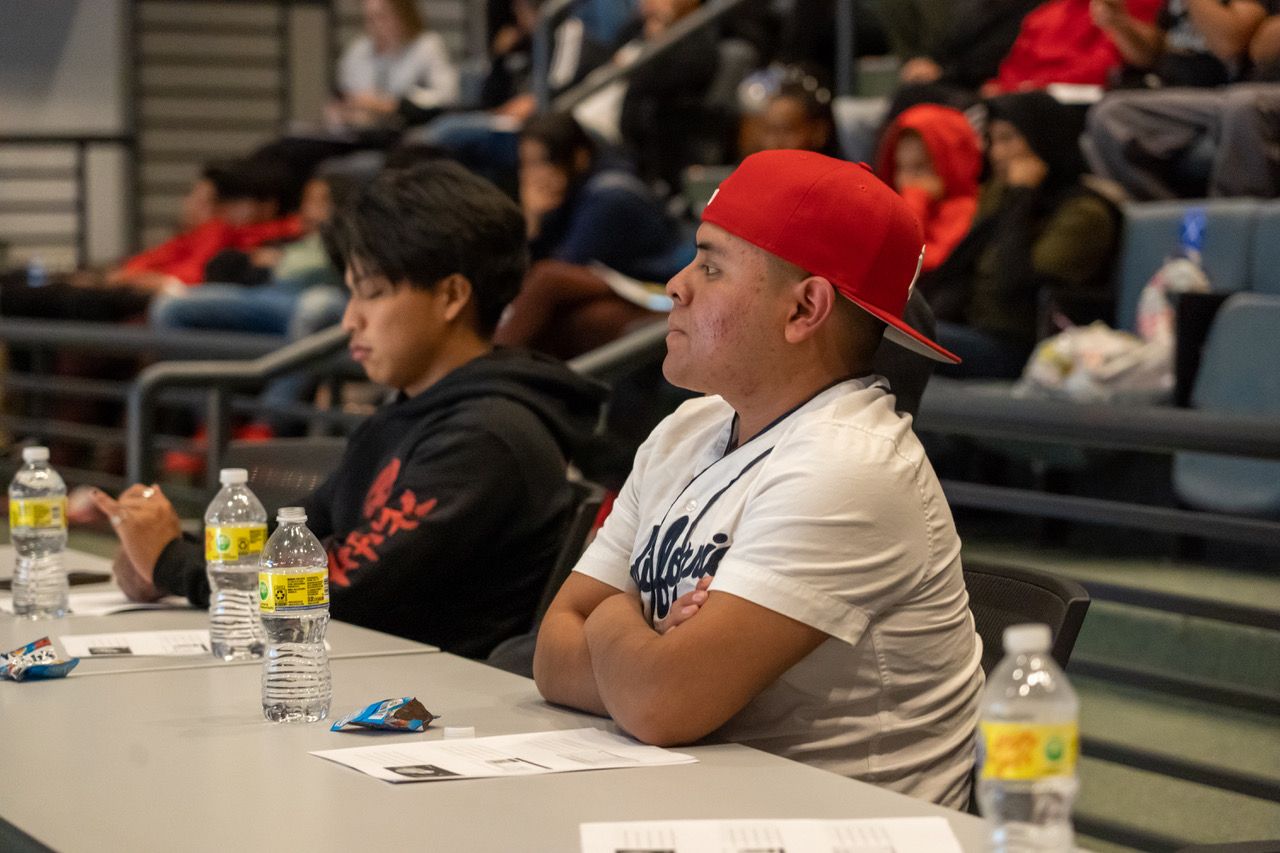

Besides their traditional classes, the group of 55 students, ages 17 to 21, meet multiple times a year at the CPS Education Center for focused sessions. Topics range from starting a business to immigration issues. The group had their second meeting of the school year last Wednesday.

“My plans for the future are to go into nursing, but if that pathway is not available to me, then operating a business is something that I would like to do,” Hernandez said.

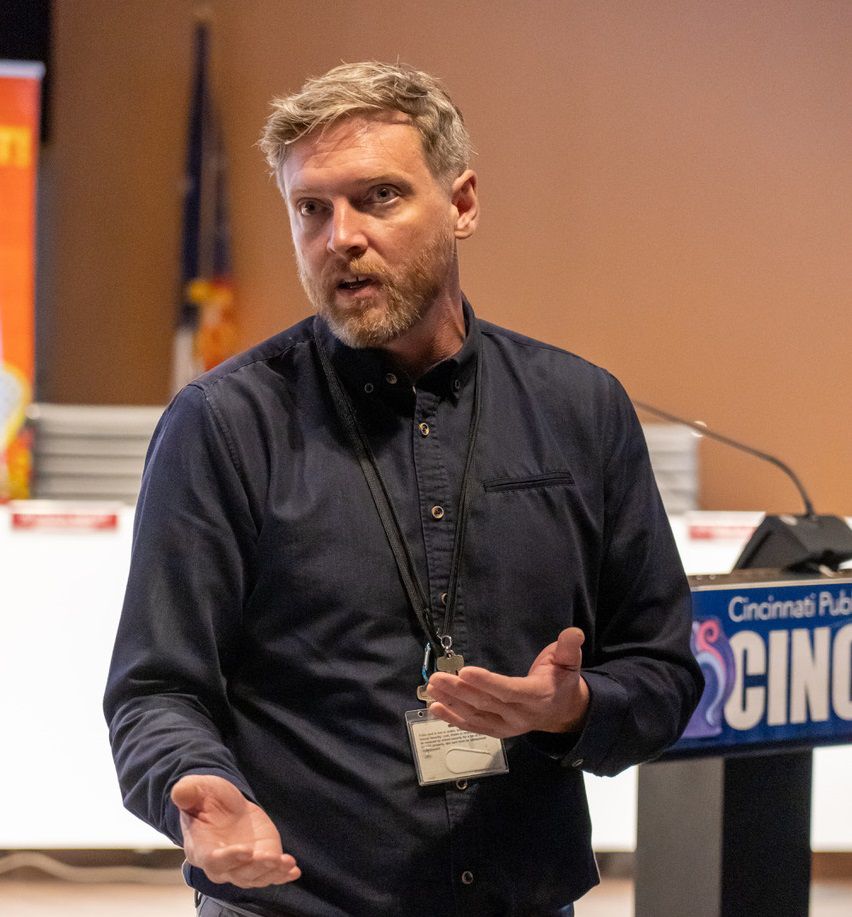

The program is run by Adam Cooper, English As Second Language Council chair in CPS schools.

It developed out of conversations between counselors, social workers and teachers who wanted to improve four-year graduation rates among many English learners and many multicultural students, Cooper said. The group witnessed many of the students in that population become disengaged from school and stopped attending classes, Cooper said.

While Hernandez grew up in Los Angeles, many of the students in the programs are immigrants or refugees who had limited or interrupted formal education before coming to Cincinnati, Cooper said. Some face additional challenges regarding immigration status.

Withrow University High School, for example, offers business classes, but language barriers and a lack of foundational learning in the past leave many of these students unlikely to meet state requirements to pass, Cooper said.

For most in the program, going straight into college or enlisting in the military isn’t an option. Finding a typical employment situation might also prove to be a challenge for them, Cooper said.

“A significant population of these students don’t really see a purpose for graduating from high school because they don’t see themselves as being able to pursue traditional post-secondary options,” he added. “We’re working to not only re-engage them as students, but to set them up to find some form of success as well.”

Creating opportunities for those in need

The program launched as a pilot in 2021 with a handful of 11th- and 12th-grade English as a Second Language (ESL) at neighboring Gilbert A. Dater and Western Hills high schools. This year, it expanded to include upperclassmen at two additional schools: Aiken High School and Withrow.

A new cohort is set to begin in the fall. Plans are to grow the pilot program in the future, Cooper said.

“I would love to expand that to even younger students to engage them before they show that disinterest,” he added.

Right now, students are recommended for the program by their school counselors based on information students share about what they plan to do once they’ve graduated or finished high school.

Cooper stressed the program isn’t just for those who aren’t sure what the future holds. They also want to offer opportunities for students who show a desire in business.

Some of the business types include things like health care, or running a restaurant or convenience store. Others may decide to train to become a barber or beautician who runs their own shop.

They’re also helping students who want to pursue additional certifications and training to go into things that could also include things like IT, Cooper said.

If nursing doesn’t work out, Hernandez would like to own or run a clothing or jewelry store.

“This program proves you don’t have to be someone specific, like a doctor or something, in order to do what you love,” Hernandez said.

Developing a community of support

One of the primary partners involved in the program is Cincinnati Compass, which works with community partners to make the region more welcoming to immigrants and refugees. They do so by promoting the development and expansion of the economic, cultural and educational opportunities available to those groups.

The goal, according to Cincinnati Compass executive director Bryan Wright, is to set these young people up for success, given their specific circumstances.

“It starts with entrepreneurship, but it goes well beyond into other academic, or workforce-related training,” Wright said.

“No two cases are the same,” he added. “For some students, that may mean earning a high school degree or the equivalent, while for others, it’s providing them enough resources to go out into the world and be productive.”

Wright has a background in education himself. He’s former academic adviser and director for the International Student Affairs Office at Cincinnati State Technical and Community College. That could use the community college pathway to leapfrog to additional training opportunities, apprenticeships or four-year colleges education.

“We know your earning power increases drastically by simply getting a high school diploma, but we recognize some individuals have gaps in education that can stifle their growth academically,” he said. “When you combine those gaps in education with limited English proficiency and/or being in a new cultural or linguistic environment, being able to get a high school diploma in a traditional sense becomes more challenging.”

As part of the program, Cincinnati Compass is working with Cooper and CPS to set up relationships with organizations who have expertise ranging in everything from language services and immigration law to how to get a small business loan.

Each of the Entrepreneurship Mentoring Program meetings has a focus area.

The first event of the year in October was a broader introduction meeting where students worked to establish goals and set a vision for what they want to accomplish, whether that’s start a business or help expand a family business, Cooper said.

“They didn’t just talk about businesses, but immigration and that process,” Hernandez said. “As someone who knows many people looking for that kind of knowledge and resources, I can point them in the right direction.”

Beyond CPS staff, the program features several technical advisers, such as Gina Pinto Williams with Liberty Tax Service.

During Wednesday’s meeting, Pinto Williams offered practical advice on how to start a business. One topic they discussed was how to create a Tax Identification Number or Employer Identification Number.

Cooper is also looking to identify success stories of past CPS graduates and residents of greater Cincinnati who immigrated to the U.S. and have started their own business. Not only can they share tips and tricks, Cooper said, but they’ll serve as proof that doing so is possible.

One mentor is Araceli Ortiz, the CEO of Cincy Cleaning Co-Op, a residential cleaning company. She and a group of local cleaning professionals worked with the organization Co-op Cincy in 2018 to form a company that enabled all the cleaners to make a good living while also having a say in decision-making.

Several of the co-owners of the business are immigrants. Ortiz is from Mexico.

Ortiz and other potential mentors plan to speak at the third and final meeting of the year in March. Cooper is still looking for participants.

Following the spring event, CPS plans to connect eligible students with case managers for life beyond graduation.

“The process can feel very daunting. I know that firsthand,” Ortiz said. “I want to support students to reach their dreams and become business owners.”

While the program may be focused on students learning about opening their own businesses, it also connects them with community partners such as the Immigrant and Refugee Law Center (IRLC). The organization provides free legal immigration services to immigrants and refugees in southwest Ohio, northern Kentucky, and southeastern Indiana.

Cooper said students had a lot of questions about their pathway to citizenship and the formal immigration process, and what effect that will have on them in the business world.

“Understanding that immigration is one the biggest barriers faced by our immigrant students, we want to make them aware that immigration status is not a barrier to becoming entrepreneurs and being successful after graduating high school,” said Mayra Casas Jackson, a paralegal and case manager with IRLC.

IRLC’s participation focused on identifying students with potential immigration remedies they could use while representing them with U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services or Immigration Court.

Programs, like the one through CPS, help IRLC connect with the community members who may not be aware of their services, Casas Jackson said. That’s invaluable, she added, to establishing trust, especially those afraid to might otherwise be afraid to disclose their legal status.

“Working with schools and the students makes it easier for us to reach out to their families and communities because the school has already created that trust,” Casas Jackson said.