The first time Ann Councilman, a registered nurse in Greensboro, realized how bad the coronavirus could be, she was helping out in an intensive care unit at Cone Health early in the pandemic.

“On that particular day, it became very real for me. What I witnessed, the work that was occurring, how sick the patients were that were in that unit. That was when I really realized that this was not just a surge that was going to go away,” she said. “We were in this for the long-haul.”

Almost everyone has that one moment when the coronavirus pandemic went from an overseas abstraction to something more, a real threat to daily life.

For some, that might be the day they cancelled the NCAA tournament. For others, maybe it was the day they locked the door on their business as the economy shut down. Or maybe it was the day their grocery store ran out of toilet paper.

For Dr. David Wohl, who specializes in infectious diseases at the UNC School of Medicine, it was when cases started showing up in Europe.

“This is not business as usual. This is not an ‘across-the-ocean’ type problem. This is our problem now,” he remembers thinking in February 2020.

In Wilmington, Catch owner and Chef Keith Rhodes said he got home after work one night and his wife was doing the books in the bedroom. “I just remember looking over at her and she had her list out, and there was nothing on the list.”

“She’s looking at me and I’m looking at her. It was just really gut-wrenching that we were used to being super busy all the time, and this moment, at that time, there was nothing. We didn’t know what was happening,” Rhodes said.

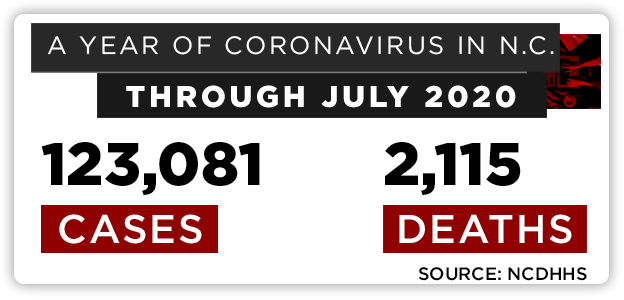

For North Carolina political scientist Michael Bitzer, that moment came as he was comparing the death toll to filling different college football stadiums.

“At one point, we had filled Wake Forest. And then it was N.C. State, and then it was Chapel Hill. When it started to hit things like Clemson and Tennessee,” the gravity of the situation came into focus, Bitzer said. “The numbers kept going up.”

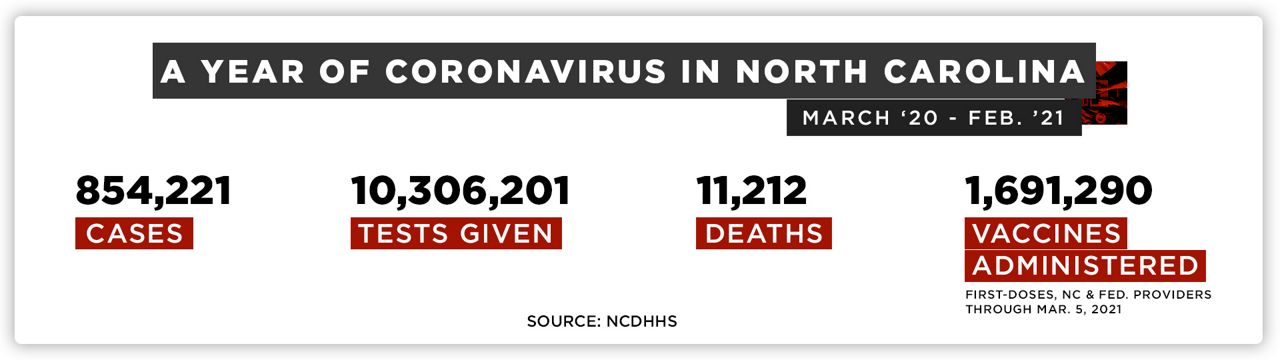

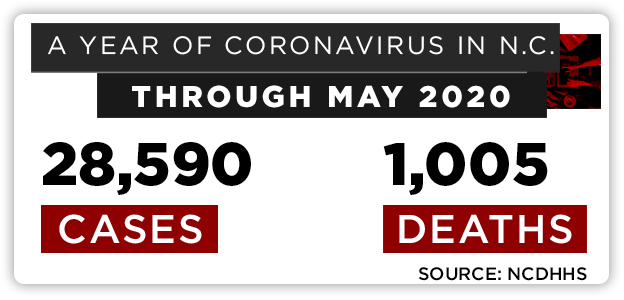

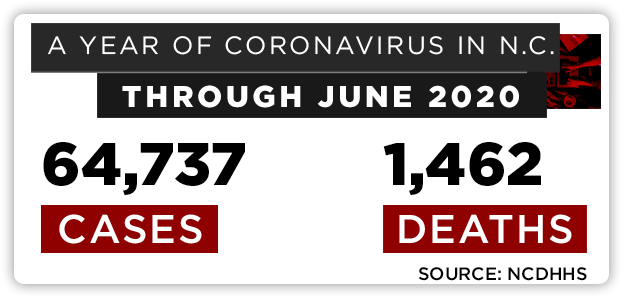

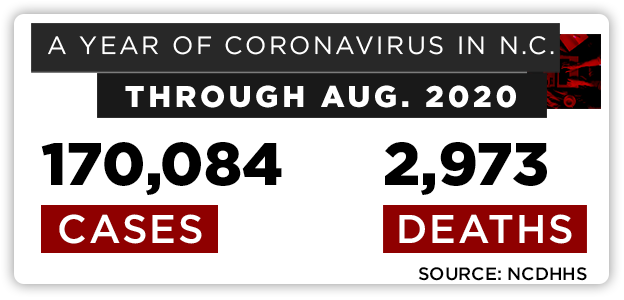

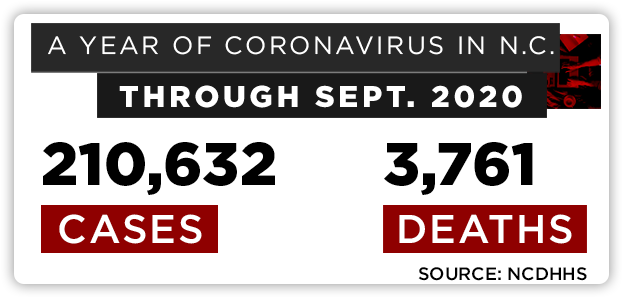

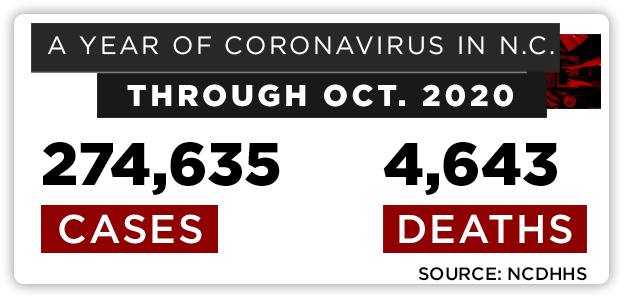

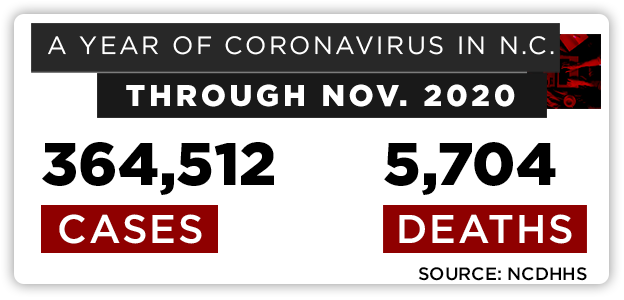

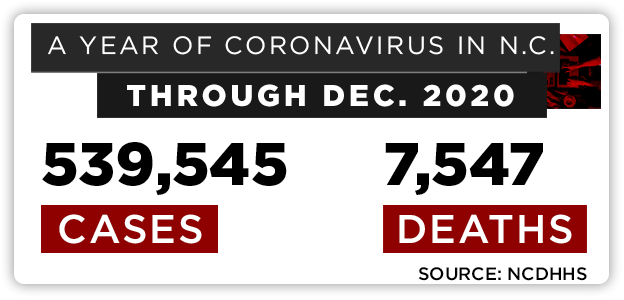

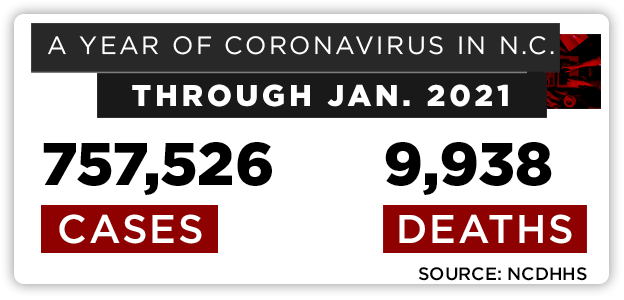

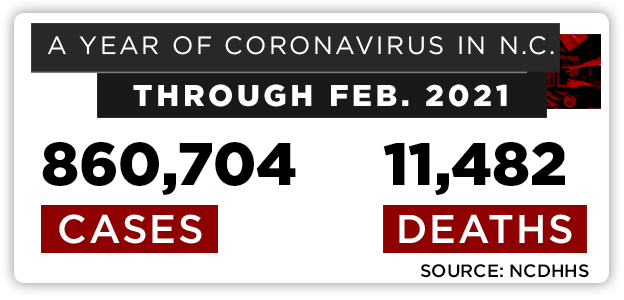

Since the first documented cases of COVID-19 reached North Carolina on March 3, 2020, more than 11,500 people have died from the virus, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

Nationally, more than 500,000 people have died from the virus. To put that in perspective, the population of Raleigh is about 475,000, according to the latest Census Bureau estimates from 2019.

It’s been a full year since the first case appeared in North Carolina and Gov. Roy Cooper issued the first in a series of emergency orders aimed at controlling the pandemic. The state has been through an economic shutdown, massive job losses, protests over racial justice, a hard-fought election and a huge spike in cases over the winter.

At the one-year mark, the United States is in the biggest vaccination campaign in the country’s history. In North Carolina, the numbers that have become part of daily life, new cases, hospitalizations and percent positive, continue to improve. Some of the restrictions on gatherings and businesses have started to ease up.

There’s a lot the world does not know about how the coronavirus pandemic got started. In January, a team from the World Health Organization was in China to try to track down how this new virus started infecting humans, most likely in the central Chinese city of Wuhan.

Scientists suspect the virus jumped from an animal to humans, possibly from a bat, in December 2019. But just how and where and when remains a mystery.

“As of 5 January, 59 people in the east-central city of Wuhan have been infected with the mystery virus, with 7 in a critical condition, according to the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission,” the journal Nature reported in early January 2020.

In those early weeks and months, the world watched China as Wuhan was locked down and the case numbers there grew, reminded of other epidemics like SARS and swine flu.

The first case of the virus in the United States was confirmed in a Washington state man on January 21, 2020. The man had just returned from Wuhan.

A news release from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announcing the case noted, “This is a rapidly evolving situation.”

Then-President Donald Trump downplayed the threat of the virus.

“In an interview with CNBC on Jan. 22, Trump said, "We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

Two days later, China moved to quarantine Wuhan, locking down the city of 11 million.

The WHO declared a global public health emergency Jan. 31.

Global air travel restrictions started coming on Feb. 2.

The next day, the United States declared a public health emergency.

“While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low,” then-Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said at the time.

By late February, the president continued to dismiss the virus in public, but one of the CDC’s top scientists had a different message: "We expect we will see community spread in this country," Dr. Nancy Messonnier, the CDC's director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in a call with reporters.

"It's not so much a question of if this will happen anymore, but rather more a question of exactly when this will happen and how many people in this country will have severe illness," she said on Feb. 26.

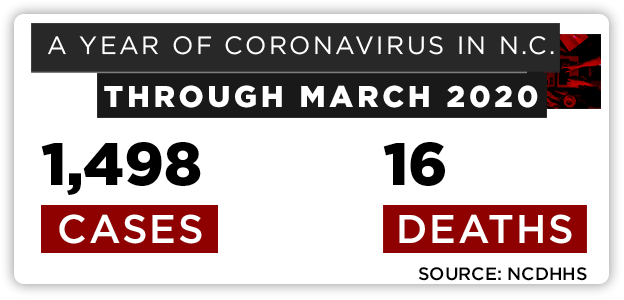

In North Carolina, public health officials announced the first case in the state March 3.

A Wake County resident visited a nursing home in Washington state before coming back to North Carolina and developing symptoms.

“I know that people are worried about this virus, and I want to assure North Carolinians our state is prepared,” the governor said at the time.

“Our task force and state agencies are working closely with local health departments, health care providers and others to quickly identify and respond to cases that might occur.”

In North Carolina—and the rest of the country—life changed quickly in March.

On March 10, Gov. Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency.

On March 14, the governor banned gatherings of more than 100 people and shut down the state’s public schools for two weeks. Students never returned to the classroom that spring.

Colleges and universities sent students home for spring break and told them to plan not to come back.

On March 12, the NCAA cancelled the 2020 college basketball tournament.

Across the country, states started locking down. Images of overwhelmed hospitals in New York City flashed across news broadcasts with stories of makeshift morgues having to be set up to handle the victims of the virus.

Another executive order on March 17 shut down restaurants and bars in North Carolina. Indoor bars would be closed completely for almost a year.

Cooper said the restrictions the state enacted were hard choices. “We did not come to this decision easily, but North Carolina must keep fighting this pandemic with the right weapons. During this time of uncertainty, I will keep working to protect the health and safety of North Carolinians and keep our state’s economy afloat,” he said.

All but the most essential workers were sent home, tens of thousands lost their jobs. Companies that could have employees work from home shut down their offices. Parents scrambled to keep some kinds of normalcy for their kids as school systems tried to figure out how to keep teaching virtually.

On March 24, a person in their late 70s from Cabarrus County was the first to die from the virus in North Carolina, according to DHHS.

“This is a stark warning that for some people COVID-19 is a serious illness. All of us must do our part to stop the spread by staying at home as much as possible and practicing social distancing,” Cooper said.

Scientists and public health officials around the world scrambled to get a handle on the virus. The guidance in North Carolina in March was, essentially, stay home, wash your hands and practice social distancing.

Public health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci and North Carolina DHHS Secretary Dr. Mandy Cohen became household names.

“North Carolina is now considered to have widespread transmission of the virus, which means people who have tested positive cannot trace where they were exposed to the virus,” DHHS said in a statement.

At 5 p.m. on Monday, March 30, the state’s one-month stay-at-home order began, essentially shutting down North Carolina, banning gatherings of more than 10 and directing people to stay home except to get groceries, help a family member or get exercise.

Stuck at home with partners, kids or roommates, kitchen tables turned into classrooms, offices or experimental bakeries.

It was a strange time. People had to learn how to cut their own hair, use something called Zoom to go to work, and watch spring arrive without being able to go anywhere to enjoy it. There was a run on toilet paper.

Keeping up with daily virus numbers and new research about the virus became a passtime for many. Scrolling through social media got a new name: “doom scrolling.”

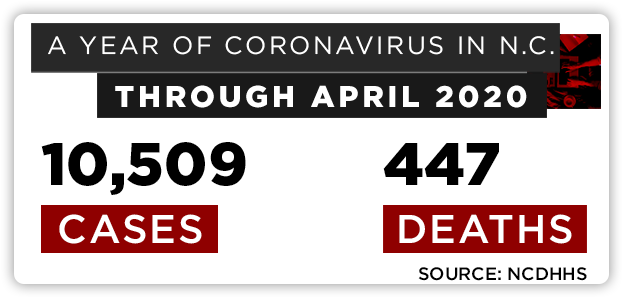

Between March and April 2020, unemployment exploded from 4.3% to 12.2% in North Carolina.

More than 600,000 people filed new unemployment claims with the state between March 15 and the end of April, according to the state Department of Commerce.

Cities and big venues started cancelling events into the summer.

Eventually, even the North Carolina State Fair would get cut.

On April 15, 2020, Cooper said, “This virus is going to be with us until there is a vaccine, which may be a year or more away.

"That means that as we ease restrictions, we are going to enter a new normal. We want to get back to work while at the same time preventing a spike that will overwhelm our hospitals with COVID-19 cases,” said Cooper.

North Carolina’s most strict say-at-home order stayed in effect until May 8.

As much of the nation stayed under lockdown, politics didn’t stop. Near-daily briefings from the White House sent mixed messages to Americans stuck at home.

At those briefings, the president criticized the nation’s governors for shutting down state economies. “When somebody is the president of the United States, the authority is total and that’s the way it’s got to be,” Trump said in mid-April.

Trump and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo clashed in the national spotlight about the shutdown orders in the president’s home state.

In North Carolina, many Trump supporters and others criticized the governor’s order here.

Hundreds of people protested at the governor’s mansion in Raleigh in late April, calling on Cooper to reopen the state.

The governor “needs to put his ear to the ground and he needs to look out his window and see how many people are here today gathering,” Dee Park, 82, told the Associated Press during the protest. “It’s time to open our state again and let people get back to work and make a living.”

That early protest by the ReopenNC group would help set the tone for the long election season to come, when the political fate of Cooper, Trump and others would depend on how they responded to the pandemic.

The pandemic posed a major challenge for elected leaders in North Carolina and Washington D.C., and the fact that it was an election year only added heat to the fire.

Before the virus hit, the economy was doing well. Donald Trump appeared to be in a good position to win another term as president, despite deep divisions in the country over his leadership.

The president was criticized for downplaying the seriousness of the virus and appearing to be more concerned with the economy than controlling the pandemic.

The Trump administration put much of the response to the states. In mid-March, North Carolina and most other states started locking down, the White House announced “15 Days to Slow the Spread.”

That meant staying home, avoiding restaurants and bars, and homeschooling children.

Seven days later, the president’s message changed. “We cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself,” Trump tweeted on March 22.

Daily briefings from the White House coronavirus task force became daily must-see TV for many Americans as Vice President Mike Pence, infectious disease specialist Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health officials updated the nation.

The president’s appearances at those briefings would turn into wandering sessions with the press, at times blaming China, clashing with reporters and airing grievances.

He promoted unproven cures for the coronavirus, most notably the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, and mused about injecting bleach into the body.

Protesters, some carrying guns, held rallies in state capitals calling on governors, mostly Democrats, to end the shutdowns. Trump called on the protesters to “liberate” Michigan, Virginia and Minnesota.

In May, as the number of COVID-19 deaths in the United States approached 100,000, Trump said, “We have met the moment and we have prevailed.”

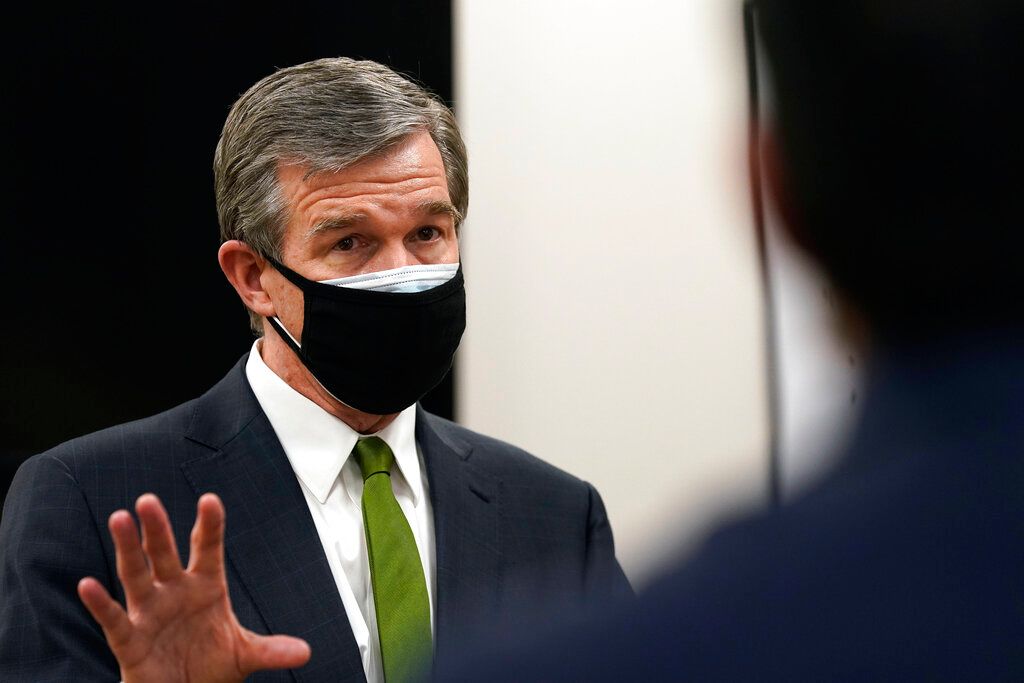

But while Trump downplayed the virus, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, along with DHHS Secretary Dr. Mandy Cohen, struck a different note.

In regular news conferences, the governor and state public health officials pushed the now-familiar mantra of wearing a mask, washing hands and waiting six feet apart. They urged people to get tested.

In August, as it became increasingly clear that the virus was not going away anytime, Cooper said, “Other states that lifted restrictions quickly have had to go backward as their hospital capacity ran dangerously low and their cases jumped higher. We will not make that mistake in North Carolina.”

Many Republicans in the state criticized the governor for shutting down the economy and reopening slowly, making it the top issue in the election between Cooper and Lt. Gov. Dan Forest.

“Certainly, 2020, at the statewide level, showed us that most North Carolinians were comfortable with Roy Cooper’s approach,” Catawba College political science professor and longtime state politics watcher Mike Bitzer told Spectrum News 1.

Trump and Cooper were in very different positions as they wrestled with controlling the pandemic while running for re-election. Cooper won his reelection handily, but the GOP kept control over the General Assembly.

Trump refused to accept his loss and pushed false narratives and conspiracy theories in an attempt to overturn the results of the election.

The effort ended with a bloody attack on the U.S. Capitol as Congress met to overturn the election, leaving five dead including a police officer.

The former president’s legacy will have a lasting impact on North Carolina.

“Most Republicans are now espousing Trumpism as their guiding principal,” Bitzer said.

The most prominent example of that in the North Carolina GOP may be Rep. Madison Cawthorn, who was elected to the 11th Congressional District in the western corner of the state.

Cawthorn, the youngest member of Congress, spoke at that Trump rally before supporters attacked the Capitol. He has been seen as a rising star in Trump’s GOP, with regular appearances on outlets like Fox News.

Most recently, in late February of this year, he spoke at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference in Florida.

Joe Biden took control of the White House when he was sworn in as president on January 20th. Since then, the messaging around the virus and the federal coordination has changed dramatically.

Trump was often criticized for ignoring or politicizing the science around the pandemic.

Facing a historic, once-in-a-century public health crisis, politics and science were bound to blend together. And both evolved rapidly over 2020.

When the virus started to spread, researchers and doctors scrambled to learn more about the virus and how to treat patients suffering from severe breathing problems.

As people around the world watched the cases and death counts climb, they also watched in real time as science and medicine worked to figure out what to do to stop the pandemic.

Before the coronavirus hit, Dr. David Wohl, at the UNC School of Medicine, was focused on HIV and had spent time in Liberia fighting Ebola. Now he’s one of the doctors running the vaccine and testing sites at UNC.

“You could see the gathering storm clouds and the tell-tale signs of something that’s turning into something that’s bigger than you want it to be,” Wohl said in an interview with Spectrum News 1.

He said those warning signs started coming in February. “Once we started seeing cases in Europe, it was very clear to me that this had crossed a line,” he said.

That’s when he realized, “This is not business as usual. This is not an ‘across the ocean’ type problem. This is our problem now.”

Dealing with treating coronavirus patients as the science keeps evolving reminded him of working with Ebola patients in Africa, Wohl said. Five or six years ago in Liberia, there wasn’t a treatment, there wasn’t a vaccine, “we’re developing diagnostic tests on the fly,” he said.

“Dealing with Ebola and other hemorrhagic fevers, the same thing happens but on a much smaller scale and scope,” he said. “Emerging data come out just as you know you’re keeping track of it, you always feel like you’re one step behind.”

“In the beginning it was all about the epidemiology: where’s it hitting, how many cases, how many deaths, how many people in the ICU. But it’s really shifted. That just shows it took science a little while to plant the seeds, let them germinate, and now we’re getting some fruits of that labor,” Wohl said.

“It’s really helping us understand, ‘How do we put this all together to help people?’” he said.

In the year since the pandemic really started to hit the United States, researchers and doctors have learned more every day about how to treat patients with the coronavirus and prevent more people from getting it.

“Generally, in this outbreak, in this pandemic, science has been mostly right. People like to point out the exceptions, because nobody’s got a crystal ball. But we generally know what we’re talking about,” Wohl said.

The keys to fighting the pandemic are what people in North Carolina hear all the time now: wear a mask, wash your hands, practice social distancing and get vaccinated.

“We’ve got to get our act together. And I think we are. I think people are taking it more seriously. Instead of this being something you’ve heard about or saw on TV or read in the newspaper, people now know people who’ve gotten sick. People now know people who’ve died,” Wohl said.

The first two vaccines, from Pfizer and Moderna, were developed in record time and are about 95% effective. Research shows the vaccines are safe and allergic reactions are rare.

A third vaccine, from Johnson & Johnson, just got emergency approval from federal regulators in the last days of February.

The new vaccine is about 65% effective, but only requires one shot. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines need two shots to be fully effective.

Looking at the numbers coming down in North Carolina and around the country, Wohl said, “I’m optimistic but cautiously optimistic. I’m worried about the new variants.”

The vaccines, he noted, are effective against the new variants. But the best way to stop new variants is to keep wearing a mask and social distancing so they don’t spread.

“The masking, the distancing, that will work. But I am worried about the percentage of the population that are not able to do that consistently,” he said.

For the future, Wohl said, “I’m looking at April. April will help me understand if the trend we’re seeing right now, over January and into February, continues.”

“It will either continue and that will be a really good sign that despite variant spreading, more people are getting vaccinated, the messaging is consistent, we’re on the right track for summer,” he said.

“If in April we start to see the death rates go up again, infections go up again, pockets in the country that are exploding, then I think we have a problem. We’re not out of the woods,” Wohl said.

New guidelines from federal public health officials say people who are fully vaccinated can have small gatherings indoors without masks or social distancing. Vaccinated people can also have small gatherings with people who have not gotten the shots yet.

"Fully vaccinated grandparents can visit indoors with their unvaccinated healthy daughter and her healthy children without wearing masks or physical distancing, provided none of the unvaccinated family members are at risk of severe COVID-19," the CDC said in the new guidance released March 8.

So for the first time in more than a year, public health officials say it's safe for grandparents to hug their grandchildren.

When the stay-at-home order came down in North Carolina, Charlotte restaurateur Jeff Tonidandel remembers he was working on picking our equipment for the sounds system in his new restaurant.

“So I’m here just really excited and then it’s like, ‘oh, I have to go to the other restaurants and let go 75, 80% of our staff,” he said, speaking outside a new restaurant in the Midwood neighborhood. “You’ve got all this excitement over here and then you get there and you’re tearing up.”

Tonidandel and his wife Jamie Brown own Crepe Cellar and a couple other restaurants in Charlotte’s NoDa neighborhood. They’re getting ready to open Supperland in Midwood this month.

They switched their restaurants to take-out only and have gradually been able to bring back table service and employees.

“The rules are just changing all the time,” he said. “We really just have to be nimble and be able to do a lot of things and be able to make changes quickly.”

“The staff has taken on these challenges really well and they’ve made a lot of sacrifices over the last year. So it’s great that we’re still operating and seeing the light at the end of the tunnel.”

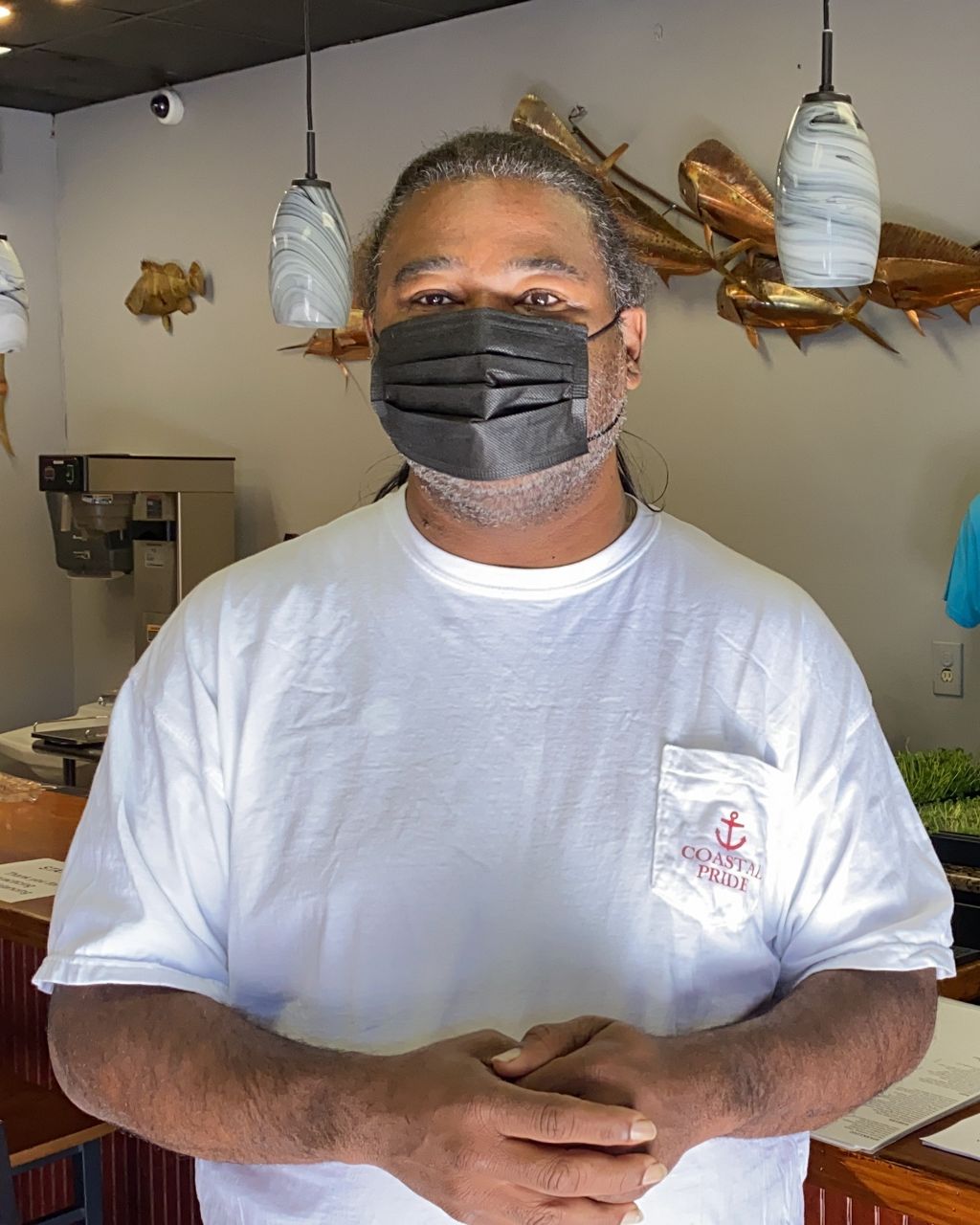

In Wilmington, Chef Keith Rhodes had a similar experience.

“We are a casual fine-dining restaurant that is mostly associated with special occasions, be it a birthday or anniversary or girls night out, this is what we do here,” he said, speaking from inside his restaurant Catch.

“The idea of doing only curbside and take-out was very foreign. So we quickly had to pivot,” Rhodes said. They had to re-do their menu to drop some menu items, either because of price or because they had trouble getting ingredients.

“It’s been a long journey,” he said. A year later, Rhodes said they are still at half capacity in the restaurant but they’ve been able to add more staff back.

North Carolina Economist John Connaughton, a UNC-Charlotte professor who produces a quarterly economic forecast for the state, said the hospitality industry has been one of the hardest hit.

“That sector took the biggest hit, lost almost half it’s jobs in the second quarter, and it’s been extremely slow to recover.” He said the hospitality industry has only gotten about half the jobs back that it lost last year.

“From an output standpoint, we essentially achieved that ‘V’ recovery” that the Trump administration was talking about last summer, according to Connaughton. But it’s not the same for employment.

North Carolina’s unemployment rate spiked to 12.7% in May. By December, it was back down to 6%, but that’s still much higher than the 3.7% in February of last year.

Until February 2020, North Carolina and the United States had seen128 straight months of economic growth. That’s the longest period of growth on record, Connaughton said.

“We really were on quite a ride up until this happened,” he said. And it didn’t look like anything was going to come in the way of continuing that growth.

Connaughton added, “It’s the thing you don’t expect, that you don’t see, that turns out to be throwing the economy upside down.”

“The question, and this is the big question, is what happens in the second, third, fourth quarter of 2021,” he said. “If we don’t have a fourth spike in the spring and early summer, we will likely get back to that real GDP level that we experienced in the last quarter of 2019.”

That means, if all goes well, the economy will have dipped for about a year and a half before it got back to where it was before the coronavirus pandemic hit, at least in terms of gross national product.

“But the virus is going to do what the virus does,” Connaughton said. “I have no idea what is going to happen this year.”

Federal and state lawmakers have approved billions of dollars in relief funds for people, businesses and local governments, including two rounds of direct payments to people and forgivable loans to businesses to keep employees on the payroll.

Tonidandel, in Charlotte, said the federal Payroll Protection Program helped keep his restaurants in businesses through the pandemic. “There’s been a lot of government support, PPP and those sorts of things. I can’t say how helpful those have been and those have really gotten us to where we are,” he said.

Of all the issues in politics, policy and public health in the past 12 months, the issue of reopening schools has been one of the most fraught with risk from all sides for leaders in North Carolina.

An entire class of graduating seniors lost out on their final weeks of high school. A much younger class started kindergarten by learning how to use video conferencing tools like Google Classroom.

School systems have started opening for in-person learning in North Carolina with varying plans for alternating days and keeping kids safe. Some school systems have had a combination of virtual and in-person classes since the beginning of the school year, but many children in the state have not been back in class for almost a full year.

On Feb. 2, Gov. Roy Cooper called on North Carolina schools to reopen. “Protecting the health and safety of the people of this state, especially our children and our teachers, has been our goal,” he said.

“We know school is important for reasons beyond academic instruction. School is where students learn social skills, get reliable meals, and find their voices. Research done right here in North Carolina tells us that in-person learning is working and that students can be in classrooms safely with the right safety protocols in place,” Cooper said.

Even when students are back in class, they still have to practice social distancing and wear masks. No matter what, students will not be able to return to a normal experience until at least the next school year.

He faced backlash from the North Carolina Association of Educators, who called on the state to get teachers vaccinated before reopening schools. The state did change course on vaccinations, opening them up to teachers starting on Feb. 24.

There’s been a separate effort by Republicans in the General Assembly to force schools to reopen.

The governor vetoed that bill in late February. “Students learn best in the classroom and I have strongly urged all schools to open safely to in-person instruction and the vast majority of local school systems have done just that,” Cooper said in a statement.

He said he vetoed the bill because allowing middle and high school students back in classrooms violates state and federal public health guidelines. And, the governor said, “It hinders local and state officials from protecting students and teachers during an emergency.”

On March 4, the State Board of Education adopted a new set of safety guidelines from DHHS and called on all public schools in North Carolina to reopen.

Universities have faced challenges of their own to reopen. When the biggest public universities in the state tried to reopen in August, UNC-Chapel Hill, N.C. State and East Carolina University, they had to close again for the rest of the semester as case numbers rose.

Students are back on campus this year, but some students continue to gather, including a well-publicized incident when UNC students rushed Franklin Street after a win over Duke in February.

Starting at 5 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 26, the governor eased up some of the coronavirus restrictions. Cooper ended a nightly curfew that had been in place since December and allowed bars to open for indoor service for the first time in almost a year.

North Carolina’s vaccination campaign continues to pick up steam. As of March 9 more than a million people have gotten both shots of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. Doses of the newly approved Johnson & Johnson vaccine have started arriving in the state.

Teachers started getting vaccines on Feb. 24 and other essential workers like police officers and grocery store employees can start getting the shots on March 10.

It will likely be the summer before vaccines are widely available for anyone who wants one. But reports of new cases and the number of people in the hospital with COVID-19 continue to fall.

In the past year, people in North Carolina have taken more than 10 million coronavirus tests. More than 875,000 people have tested positive. As of Tuesday, 11,552 people have died from the virus.

After 12 months fighting a global pandemic, things are looking up.

North Carolina Vaccination Data