MEXICO CITY (AP) — There are two ways of remembering the Spanish siege of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital now known as Mexico City: as the painful birth of modern Mexico, or the start of centuries of virtual enslavement.

The world-changing battle started on May 22, 1521, and lasted for months until the city finally fell to the conquistadores on Aug. 13. It was one of the few times an organized Indigenous army under local command fought European colonizers to a standstill for months, and the final defeat helped set the template for much of the conquest and colonization that came afterward.

“The fall of Tenochtitlan opened the modern history of the West,” said historian Salvador Rueda, director of the city’s Chapultepec Museum.

One way of remembering the event is symbolized by a plaque that stands in the city’s “Plaza of Three Cultures” honoring Indigenous Mexico, Spanish colonialism and the “modern” mixed-race Mexico that resulted from the conquest.

The three cultures are represented by three buildings: a ruined Aztec temple, a Spanish colonial church built atop the ruins and a modern government office building constructed in the 1960s. “It was neither a triumph nor a defeat. It was the painful birth of the Mestizo (mixed-race) Mexico today,” the plaque reads.

That sentiment, preached by the government since the 1920s — that Mexico is a non-racial, non-racist, unified nation where everyone is mixed-race, bearing the blood of both conquerors and conquered — has aged about as well as the 1960s office building.

It is largely roped off because shards of its marble facing regularly shear off and come crashing to the ground, and Indigenous or dark-skinned Mexicans continue to face discrimination by their lighter-skinned countrymen.

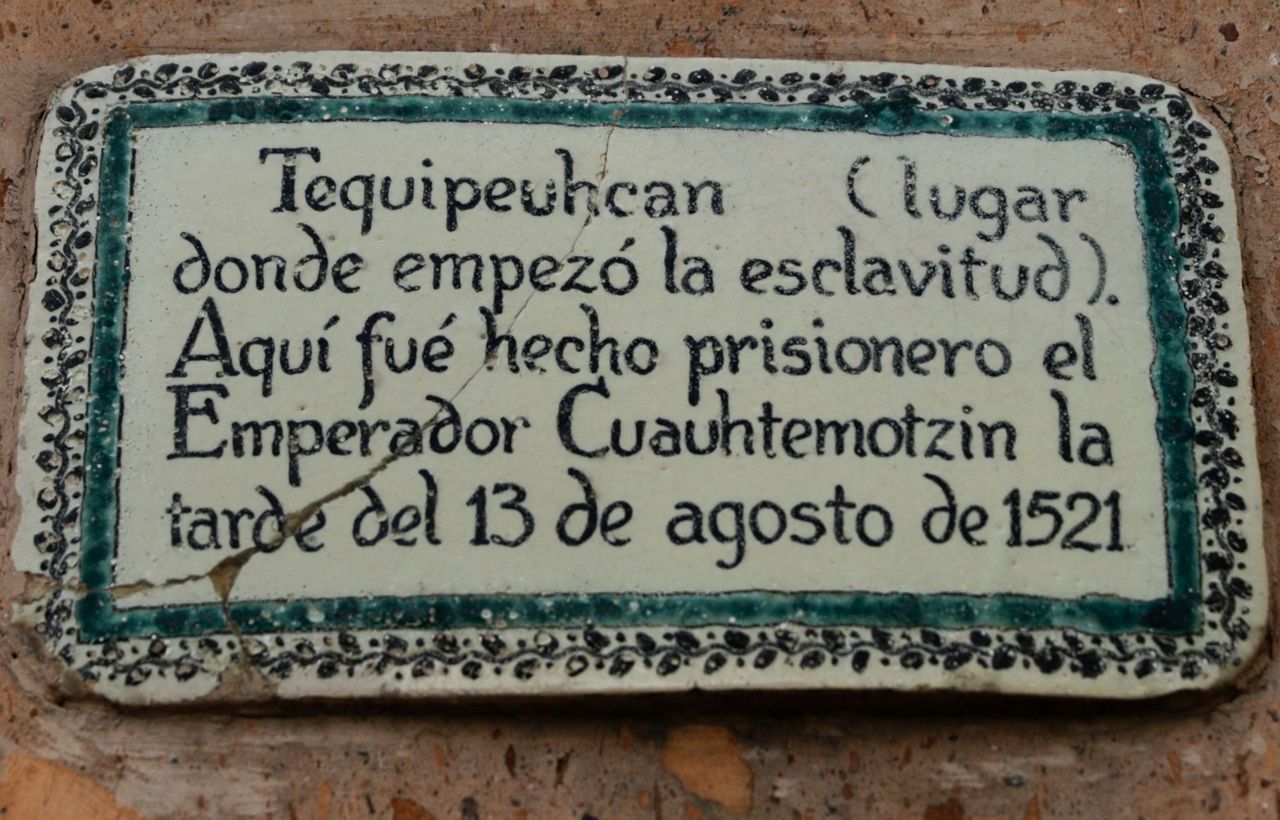

A much more enduring and perhaps accurate message is found a few blocks away on the wall of the tiny church of Tequipeuhcan, a place whose very name in the Aztec’s Nahuatl language sums it all up.

“Tequipeuhcan: ‘The place where slavery began.’ Here the Emperor Cuauhtemotzin was taken prisoner on the afternoon of Aug. 13, 1521,” reads the plaque on the church wall.

Mexico City’s current mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum, put it this way: “The fall of México-Tenochtitlán started a tale of epidemics, abuses and 300 years of colonial rule in Mexico.”

That was to become the rule throughout the hemisphere over the next three centuries. Colonizers stole the land from indigenous peoples and made them work it, extracting the wealth for the benefit of the colonizers.

“The Spaniards seemed so convinced this model worked well that (Cortés' lieutenant Pedro) de Alvarado was set to go launch an invasion of China from the port of Acapulco when he got tied up in another battle in west Mexico and died,” said David M. Carballo, professor of archaeology, anthropology, and Latin American studies at Boston University and author of the book “Collision of Worlds.”

He said the conquest of Mexico “truly made the world globalized, as it connected the transatlantic to transpacific world and all the habited continents. That kicked off what we now call globalization.”

Cortés and his 900 Spaniards — plus thousands of allies from Indigenous groups oppressed by the Aztecs — started the siege on May 22, 1521. They had entered Mexico City in 1520, but had been chased out with great losses a few months later, leaving most of their plundered gold behind.

But the Spaniards were uniquely prepared for a war of conquest. They had spent much of the preceding seven centuries fighting wars to reconquer Spain from the Moors. Amazingly, they were even able to bring their experience with naval warfare in the Mediterranean to bear in the battle for the Aztec capital, located in a high-mountain valley more than 7,000 feet above sea level and hundreds of miles from the sea.

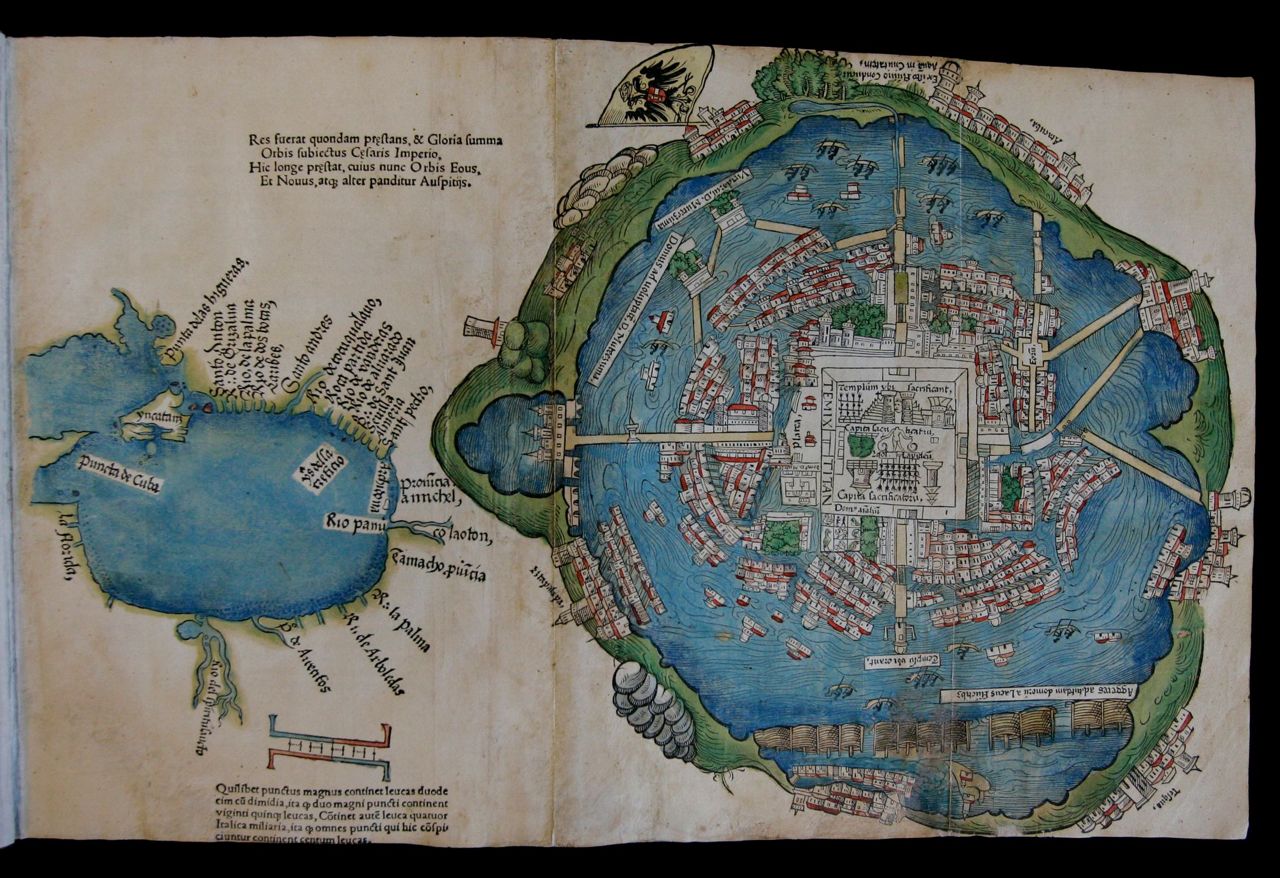

Tenochtitlan was completely surrounded by a shallow lake crossed by narrow causeways, so the Spaniards built attack ships known as bergantines — something akin to floating battle platforms — to fight the Aztecs in their canoes.

It bogged down into a brutal, monthslong series of battles for control of the elevated earthen causeways that led into the city.

The campaign was never a predetermined defeat for the Aztecs. They scored a number of victories, took scores of Spaniards prisoner and even used captured Spanish weapons against the conquistadores.

At one point they took about 60 captured Spaniards and sacrificed them one by one — probably by tearing their still-beating hearts from their chests — on battlements or temple platforms in full view of the rest of the Spanish. Even the conquistadores admitted the effect was terrifying.

But the Spaniards were able to draw on their experience of sieges during the recently concluded Christian Reconquista of Muslim Spain. They cut off supplies of fresh water and food for the city. Just as importantly, the bulk of their troops were Indigenous allies tired of paying tribute under Aztec domination.

The most powerful weapon in their arsenal was not their horses, dogs of war or primitive muskets. It was not even the deceit they used to capture the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma — who died in 1520 — or later, the Inca Emperor Atahualpa. The Europeans’ most effective weapon was smallpox.

During Cortés’ brief stay in Mexico City in 1520, the Aztecs had begun to be infected with smallpox, purportedly carried by an African slave the Spaniards had brought with them.

Carlo Viesca, a medical historian at Mexico’s National Autonomous University, said at least 150,000 of the city’s 300,000 inhabitants probably died before the Spaniards were able to reenter the city, and when they did, he quoted one Spaniard as saying, “We were walking on corpses.”

In the end, Viesca says, Cuauhtemoc — the last Aztec emperor — “had few troops with the strength left to fight.”

Medical anthropologist Sandra Guevara noted that smallpox assumed a form so virulent among Indigenous people not previously exposed to it — and with no immunological defenses against it — that even those who survived were probably blinded or developed gangrene in their feet, noses and mouths.

By the time the city fell, there were so many corpses the Spaniards couldn’t occupy the city fully for months. The only way to get rid of the stench was to demolish the Aztec houses to bury the dead in the rubble.

Cuitláhuac, a respected leader who succeeded Moctezuma and preceded Cuauhtemoc, died of smallpox in late 1520, before the siege began.

“If Cuitláhuac had not died, the history of Mexico would have been different,” Guevara said.

Emperor Cuauhtemoc — Cuauhtemotzin to the Aztecs — took over and fought on and skillfully led the Aztec resistance in the 1521 siege.

But in August, chased to the eastern edge of the city, he either surrendered or was captured. He was tortured, because the Spanish wanted to find the gold they had briefly looted but had to abandon in 1520. Stoic to the end, Cuauhtémoc purportedly handed the Spaniards a dagger and asked them to kill him.

He remains a figure so tragic yet revered that Mexicans have been encouraged for centuries to repeat his futile self-sacrifice. When six lightly armed army cadets were surrounded by U.S. troops at a hilltop military academy in Mexico City during the 1847 invasion, rather than surrender, they reportedly flung themselves to their deaths from the parapets. They too remain national heroes.

The failed battle to defend Tenochtitlan set the template for the ultimate futility of indigenous groups trying to fight Europeans with huge standing armies, fixed positions and sieges. Apart from some fights between Spanish and Inca armies during Francisco Pizarro’s 1536 conquest of Peru, Indigenous resistance in the Americas — and much of the world — would largely be reduced to guerrilla tactics, periodic raids and retreats into remote or difficult-to-access areas.

Some of the last armed Indigenous resistance — both in Mexico and the United States — would not be defeated until the early 1900s.

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.