This story is part of NY1’s initiative, “Street Level,” which explores the city through the history and culture of specific streets and the people who live there. You can watch the full episode in the video above and learn more about the project here.

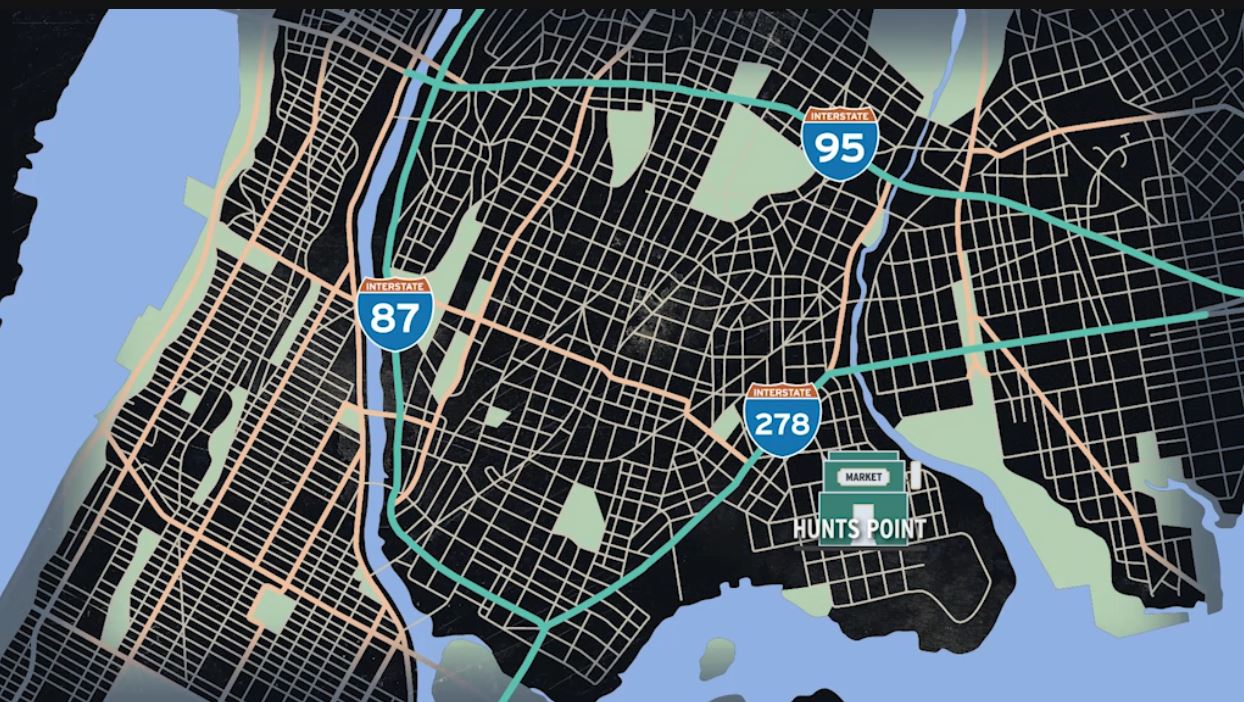

On the southeast edge of the Bronx, a small peninsula juts out into the East River. Home to the neighborhood of Hunts Point and the one million square foot Hunts Point Market, the peninsula is a key food distribution hub that connects with vendors across the city. The food that passes through Hunts Point goes on to feed the five boroughs, yet for decades the surrounding community has been isolated.

Physically cut off from the rest of the Bronx by the system of highways that made it the industrial center it is today, the Hunts Point community learned long ago to rely on itself for survival. That spirit of resiliency has motivated residents to improve their neighborhood, but now, some worry, they may soon be unable to afford the community they helped save. We spoke with some of the people who have worked to shape Hunts Point into the neighborhood it is today about the work they do and the future they see for their neighborhood.

EXPLORE: INTERACTIVE MAP OF HUNTS POINT

A Community Divided

When the Bronx officially became a part of New York City in the late 19th century, mansions lined the Bronx River waterfront. The neighborhood of Hunts Point was home to many of the city’s elites, offering a quiet retreat from the busy streets of Manhattan. Their pristine river views, however, were made less attractive by the nearby trash dump on Rikers Island. The resulting odor regularly wafted over the peninsula, driving many residents away.

In the early 1900s, the NYC subway system extended into Hunts Point, opening up the area to working-class commuters and creating a demand for affordable housing. Developers seized the opportunity, replacing the neighborhood’s large homes with apartment buildings. Infrastructural changes continued to reshape Hunts Point until the mid-1900s. The construction of the Major Deegan and Cross Bronx Expressways paved the way for industry, like the Hunts Point Market, to move in—and for wealthy residents to move out. The new roads connected the city to surrounding suburbs, offering an easier commute to and from the city to those who could afford it. In 1973, the Bruckner Expressway was completed, creating a physical barrier between Hunts Point and the rest of the borough.

A Borough on Fire

The appearance of massive highways and the exodus of the South Bronx’s wealthier residents wreaked havoc on property values in the area, leaving scores of apartments both vacant and undesirable. By the 1970s, many landlords were no longer making a profit off of their South Bronx buildings.

“The landlords wanted to get rid of their properties, and one way to do it was to burn it out and get their insurance,” remembers Firefighter John Funicane, who served out of Engine 85. “They left the building and walked away, and the city did nothing. Nobody did nothing. What happened in the South Bronx stayed in the South Bronx,” says Funicane.

For a decade, the South Bronx burned. Between 1970 and 1980, seven census districts in the Bronx reportedly lost more than 97 percent of their buildings. When the fires burned out, the South Bronx was left in ruins. The empty, charred buildings became popular spots for illicit activities—prime locations for drugs and prostitution. To those who lived there, Hunts Point was still home, but to the rest of the city, it was a literal wasteland—saddled with the burden of 40 percent of the city’s garbage.

A Push to Rebuild

For many residents, the last straw came in 1999, when Mayor Rudy Giuliani planned to build a waste transfer station along the Bronx River. Already overburdened by the quantity of garbage passing through the neighborhood, residents of Hunts Point chose to take a stand. Hunts Point native Marjora Carter, along with other community members, pushed back against the mayor’s plan. For Carter, the experience was eye opening.

“That's when I realized—oh, this only happens in communities that are poor and of color and politically vulnerable,” she says.

In the end, the community won, but that victory was only the beginning for Carter. She continued her environmental justice work with an organization she founded in 2001 in Hunts Point called Sustainable South Bronx. The organization still operates in Hunts Point today under the leadership of the Hope Program, a local non-profit dedicated to work force training.

Later, Carter turned her attention to the local business community by opening the Boogie Down Grind on Hunts Point Avenue. The cafe stands out in the neighborhood, offering a selection you don’t find in most Bronx coffee shops, like taro lattes and oat milk. “This is development that is by us and for us,” says Carter.

Carter calls her philosophy on community development “self-gentrification.” She attributes the term to Ronald Carter (no relation), a former college president in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“It’s not the development that’s the problem,” Carter says. “It’s how the development happens, who does it.” She believes that by taking the lead in local real estate development and business creation, the community can work to improve itself from within.

“Gentrification doesn't start happening when you start to see what could be the fancy coffee shop or the doggy daycares or even better apartment buildings going up for higher income people. It starts when we start telling people in communities, like, that there is no value here,” she explains.

Others, like Danny Peralta, have a different vision for the future of Hunts Point.

“When you open up the doors for people to move in that don’t understand the culture, you replace this culture. Then you replace the fabric of this neighborhood,” he says. Peralta, who serves as the Executive Managing Director of The Point Community Development Corporation, worries that gentrification of any kind will price out long-time residents. “We're seeing, you know, some of our of our neighbors, people that have lived here for a long time not only to be able to afford to live here anymore,” he explains.

Nourishing a Community

While some community members debate the future of Hunts Point, Pat Watson dedicates her time to serving the day-to-day needs of its current residents. Known to locals as “Ms. Pat,” Watson started Outreach Ministry back in 2015, distributing food out of the back of her car.

“People are out here at six o’clock in the morning, so there is a high need for food. That’s why I say, ‘hunger has no gender or no color. Everybody needs food and everybody wants food,” she says.

In partnership with the Point Community Development Center, she gives out truckloads of food every day. The food is donated by two local vendors, and available to anyone who wants it, regardless of employment status.

“We serve working people and non-working people. I do not pick and choose who I serve. It does not matter if you have a job, I still serve you,” she explains, “[There are] so many people in this world today that have a job that can't keep their head above the water.”

Feeding the people of Hunts Point is no easy task—Watson says she wakes up at 3 a.m. to drive to the market. For her, like many in the community who work towards its survival, it’s a labor of love.

“Love. That's what drives me to do that,” she says. “Love for my community, love for my neighborhood, and love for people.”