Two NYPD officers approach the home of Win Rozario on March 27. Officials say the 19-year-old had called 911.

That call, city officials say, was classified by a 911 call taker as a person on drugs, acting erratically. Rozario’s younger brother described it like this on police body camera, later released by the New York attorney general’s office.

What You Need To Know

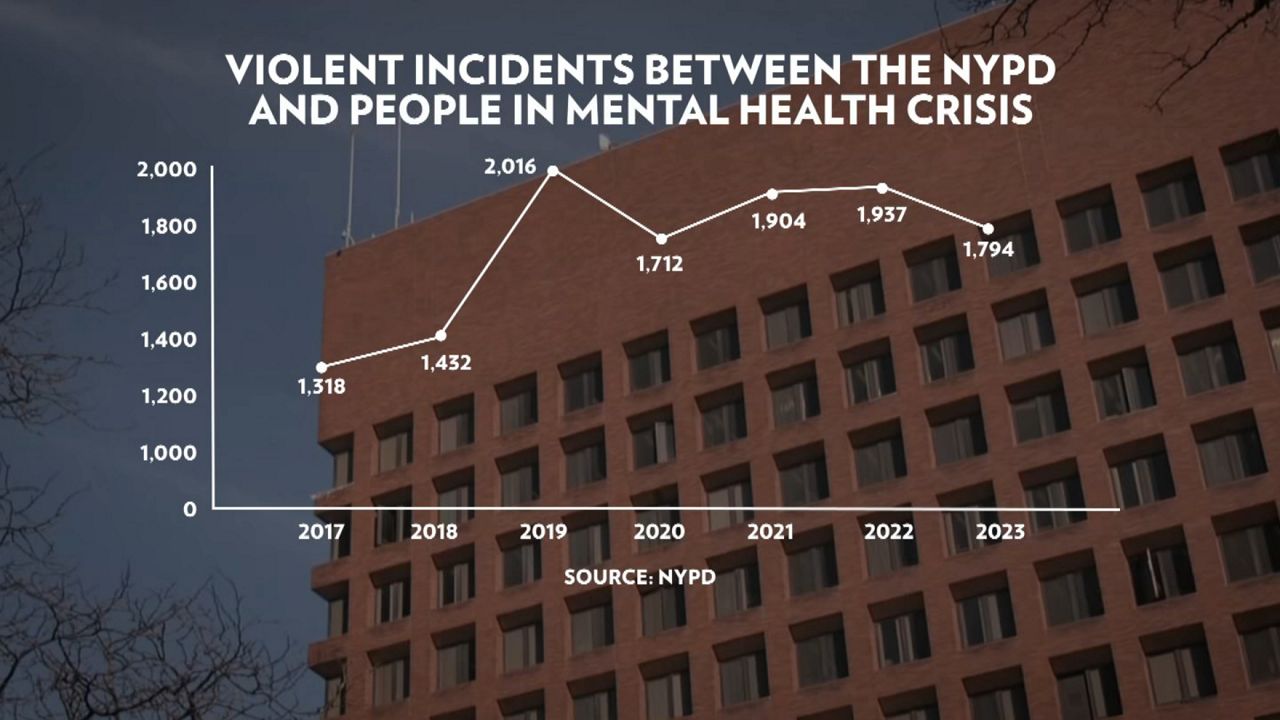

- NY1 investigated how often the NYPD uses force during mental health emergencies

- The number of violent incidents between a person in crisis and the NYPD has risen 36% from 2017 to 2023

- One in 100 incidents between a person in crisis and the NYPD turns violent

“Basically he is just going cr— he doesn’t know what he’s doing, to be honest,” Utsho Rozario said at the time.

The moment those officers entered the apartment, though, body camera footage shows the incident escalate.

Rozario grabs a pair of scissors. Officers tase him. Rozario’s mother pleads with officers not to shoot her son. They scream at his mother to get away. Rozario rushes toward the officers. A police officer shoots.

A younger brother, just 17 years old, grabs his mother off of his sibling.

“Please do not shoot my mom,” he pleads.

At no point do officers in the video appear to try to deescalate the situation. Rozario grabs the scissors again and takes a step toward the officers.

In total, the incident lasts slightly more than two-and-a-half minutes, and Rozario is shot five times.

He was pronounced dead at a local hospital.

“I’m in a lot of pain and hardly surviving,” Rozario’s mother, Notan Eva Costa, said during a rally at City Hall earlier this month. “No mother deserves to go through this. Going forward, I hope no mother ever experiences this.”

A devastated family. A mother and brother who witnessed the whole incident.

“The police was so aggressive and reckless, they could have killed me and my mom too in our own house,” Utsho Rozario said. The NYPD says it is cooperating with a state attorney general investigation into this incident.

Win Rozario is one of at least 20 people who have had a fatal encounter with police since 2015 as they were experiencing some sort of emotional or mental health crisis.

A NY1 investigation has found encounters with the police during calls with a person in crisis are some of the most dangerous. A review of data from the NYPD obtained through the Freedom of Information Law has found the number of violent incidents with police that involve a person in crisis has risen 36% since 2017, even higher in 2019 before the pandemic.

There were nearly 1,800 violent incidents last year. Those incidents included the use of a firearm five times. A taser was used 363 times — an increase of nearly 60% from 2017. Physical force was used 1,196 times.

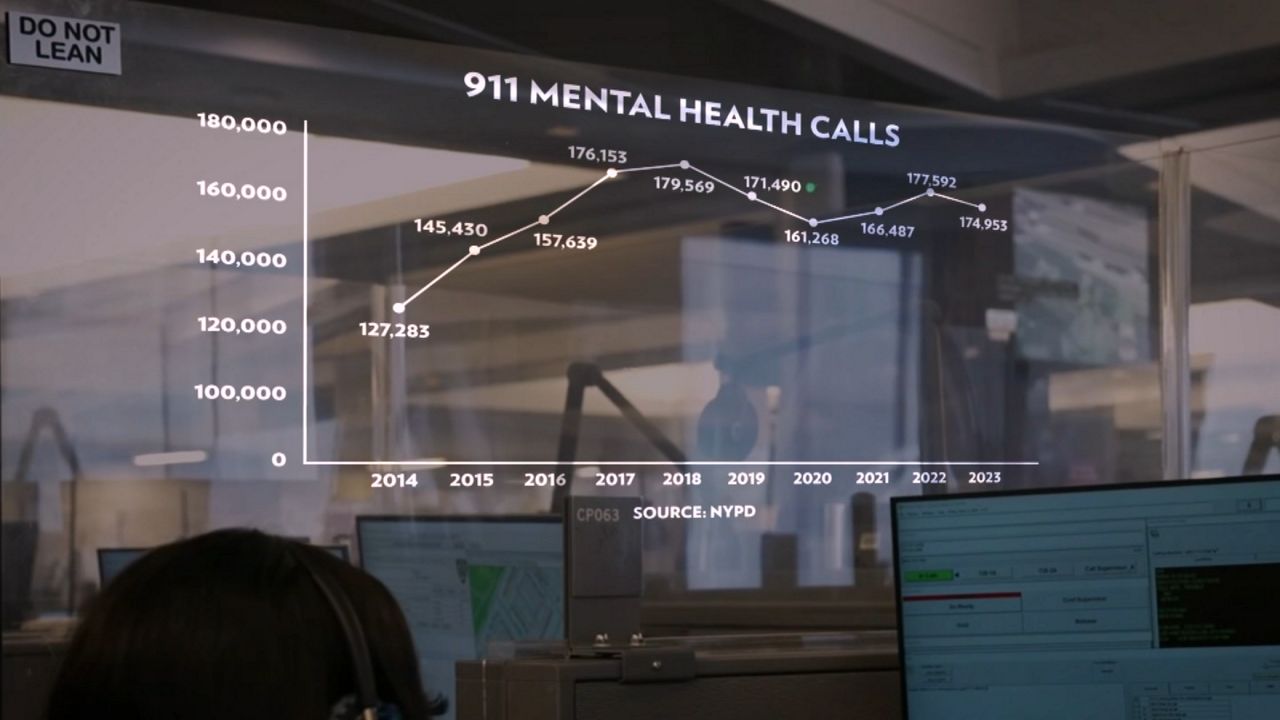

There’s more violence, in part, because there are more calls. The number of 911 calls involving a person in crisis in the last decade has skyrocketed, increasing 37%.

It all means one out of every 100 incidents the NYPD responds to with someone in an emotional or mental health crisis turns violent. And sometimes, that one could be deadly.

Eudes Pierre called 911 in December of 2021, describing to the call operator someone with a knife and a gun walking around his neighborhood in Brooklyn. Pierre was describing himself. He did not have a gun, but he did have a small pink knife.

Police responded to the scene on Eastern Parkway.

Body camera video from that night shows they tased him. Officers tried to talk him down. A knife in hand, body camera footage appears to show Pierre running in the direction of one of the officers.

He was then shot six times.

“He said, mommy, I am going outside to get something to drink. It was 4 a.m. And I said, 'Honey, there is plenty of stuff in the fridge, why do you have to go to the corner to buy something to drink?' And he hugged me, and said, 'Mommy, I love you,' and he opened the door,” said Pierre’s mother, Marguerite Jolivert.

“It didn’t take 10 minutes for them to kill my son,” she said.

His belongings are still in boxes in the family’s apartment, which overlooks where he was shot on the street below.

Pierre was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in 2019. He had attempted suicide before. His family had turned to 911 during another mental health crisis.

“I dialed 911, but on the phone and I said, ‘I don’t want police. I want social workers, someone who is going to come here, someone who is trained that can talk to him,’” Jolivert said.

That time, he was taken to the hospital.

The night he died in 2021, an investigation from the attorney general’s office found Pierre had left an extension cord tied as a makeshift noose in the bathroom, and left a note apologizing to his family.

“It’s triggering, and it’s very frustrating that it’s still happening,” said Sheina Banatte, Pierre’s cousin. “Us as impacted families, we’re not the first, but we really wanted it to be the last. People in crisis should not be killed. They should be met with compassion.”

The family is suing the city, claiming the officers did not have the proper training to deal with a person in crisis and that the shooting was negligent.

In this case, the attorney general’s office determined last year no charges could be brought against the officers. Since 2021, when the attorney general got the power to investigate fatal police encounters, charges have been brought in just one mental health case. In 20 other cases investigated by the attorney general that have concluded statewide, the use of force was legal. State law allows for deadly force when an officer’s life or another person’s life is threatened.

The shooting of Win Rozario is now under investigation by the attorney general’s office.

"Overwhelmingly when we deal with people in crisis, people in mental health crisis, they are usually responsive to the NYPD. We talk to them. We try to provide services to them,” said NYPD Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey. “It’s terrible when we do have those encounters, when our officers are going in there to help someone in crisis, and it turns out it’s a fatal encounter. It’s a terrible thing, and it’s something we don’t want to happen, and unfortunately sometimes it does happen, and we just have to constantly train, and we have to make sure our officers understand their role out there to get the person help.”

In 2015, the NYPD started what’s called crisis intervention training to try to prepare officers for encounters with people in crisis. Maddrey told NY1 the greater portion of the department had the training.

“All of our new officers for the last three to four years, they get it in the academy and this is a young department. Most of our officers out there have already received the training," Maddrey said.

But it’s not 100%.

“I would say it’s close to 100%, but I don’t have the exact numbers in front of me right now,” Maddrey told NY1.

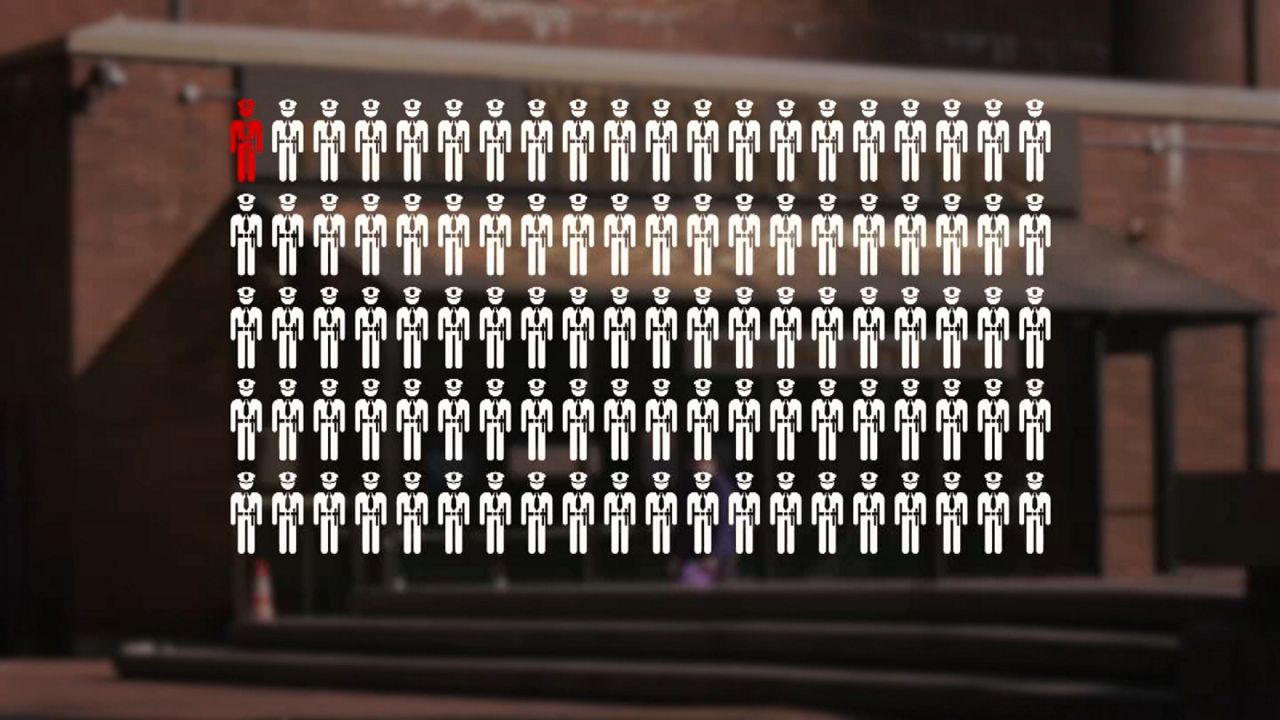

When NY1 asked for hard numbers, according to the NYPD, just 45% of the department’s uniform members have taken the in-person crisis intervention training. They say all officers receive crisis training online, and touted other trainings to deal with people in crisis, including a tactical annual refresher course.

The NYPD says the officers in the shooting death of Win Rozario, who are on modified duty, were trained in crisis intervention.

“I believe the officers were trained, but it was a few years ago when they were trained,” Maddrey said.

Maddrey would not weigh in on whether those officers acted appropriately in the Rozario case, saying the incident is under investigation.

As the investigation plays out, advocates, officials and even those in the NYPD are questioning how mental health responses can go better in the future.

“I would love to have a full-time unit where every borough, on every tour, I have officers who are working with a clinician, someone who is licensed to provide the services that are needed for people in crisis,” Maddrey said. “We do have a co-response unit. We do use the B-HEARD program. We do go out with some of our transit initiatives, but I don’t think we have enough to handle the volume right now.”