Facing the challenge of rising sea levels, the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project is lifting the waterfront and erecting a ten-foot wall deep-rooted in steel.

It’s New York City’s biggest environmental work in progress.

“The water will rise,” Ahmed Ibrahim, senior construction manager at HNTB-LiRo, said, explaining how the wall will stop the surge of water. “It’s not going to make it to the other side, so it protects the residents and the buildings on the other side.”

With a wall, elevated parkland and moveable floodgates, this $1.45 billion project will one day extend from East 25th Street to all the way downtown on Montgomery Street. For now, however, the section under construction only covers ten city blocks.

Nine years after Hurricane Sandy claimed the lives of 44 New Yorkers, work continues all over the city.

In the Rockaways in Queens, an area increasingly vulnerable to rising sea levels, new jetties are meant to protect the beach and increase its size.

“These layers of protection,” Jainey Bavishi, director of the Mayor’s Office of Climate Resiliency, explained, “will basically serve as a buffer for the storm surge and will minimize and mitigate the impacts to the community behind it.”

She thinks New York City has become a global leader in climate adaptation under Mayor Bill de Blasio.

“It’s because of the mayor’s leadership, combined with the fact that we have real resources to do climate adaptation work and we have such an aware constituency that is really demanding climate action, that we’ve been able to get as far as we had,” Bavishi said.

But not everybody agrees.

THE EVOLVING THREAT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

On August 31, the remnants of Hurricane Ida caught city officials by surprise.

Record rainfall, with an intensity of three inches in one hour, brought massive flooding and killed 16 New Yorkers, many in basement apartments.

The city’s adaptation efforts proved insufficient.

“The threat is not just on the shoreline. That’s how we defined it after Sandy,” said Steve Cohen, a professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. “But now we see the threat to the whole city. It doesn’t matter, you could live in Morningside Heights, in Washington Heights, way up high, the rain comes down just as fast there as down in the Bowery.”

Four weeks after Ida, de Blasio released a report with plans on how to face a similar storm in the future.

“The challenge that we face is just that we live in an incredibly dense urban environment with a lot of pavement, so our goal is to try to create more spaces to store storm water and for the rain water to go, because we are never gonna be able to build big enough sewers to capture the kind of rainfall we saw during Ida,” Bavishi said.

An artificial pond in Midland Beach, Staten Island, is one of those spaces, built on a stretch of land bought by the city.

Once completed, the so-called Bluebelt will drain and contain stormwater from the three surrounding neighborhoods in order to avoid flooding.

“It’s going back to what was here before the city was settled, there were a lot of these natural ponds and streams that helped to drain the area. It’s really just restoring that,” Vincent Sapienza, commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection, said.

BLOOMBERG TO DE BLASIO, AND A $20 BILLION BLUEPRINT

Mayor de Blasio took office 14 months after Sandy.

His predecessor, Michael Bloomberg, left a $20 billion blueprint filled with infrastructure plans to fortify the city. Eights years later, some of those projects are just getting started.

Daniel Zarrilli worked under both mayors as Director of Resiliency

“In 2013, we launched a $20 billion adaptation program and you can see the manifestation of that all across the city in housing elevations and hospitals and public housing and a range of investments that have been made,” said Daniel Zarrilli, who worked under both mayors as Director of Resiliency. “It also means that we’ve upgraded our building codes and our zoning codes, things that you can’t necessarily see, but are helping make us safer.”

One of those upgrades is at the Coney Island Houses, where the old basement boilers were flooded during Sandy. The brand new ones in this public housing complex are built to withstand future challenges.

“These boilers have been installed well above the flood elevation for this location, so that in any future storm that we are protected and they will be able to provide heat and hot water for the residents,” said Joy Sinderbrand, vice president of NYCHA’s Recovery and Resilience Department.

As part of the Sandy recovery program, 20 public housing campuses received new protected heat and water systems, and now the city’s housing authority is incorporating the strategy in its construction projects.

“Designing infrastructure and especially the distribution systems that go along with it does take a lot of time, and those construction projects can stretch over years because all of the buildings we are working on are occupied,” Sinderbrand said.

’A COMPLETE FAILURE OF MAYORAL LEADERSHIP’

But some experts believe New York City is hardly keeping up with the climate threat, and they see de Blasio’s tenure as a missed opportunity.

“I think there’s been a lot of discussion and planning," Cohen said. "I think we’ve had a complete failure of mayoral leadership. What I mean by that is that this has to be a priority, and it hasn’t been a priority for mayor de Blasio."

The East Side Coastal Resiliency Project started construction four years late. And work at the section at East River Park has been stopped by a lawsuit brought by community organizations unhappy with how the park will be impacted.

A sea wall for Staten Island’s East Shore has also been mired in delays.

“You have to be willing to accept the fact that not everybody is going to love everything you do,” Cohen said. “If your main objective as mayor is political popularity, it may be running for president, or for governor, or whatever the next thing is, it doesn’t suit you well for the tough choices you are gonna have to make to be the mayor of a place as complicated as New York, and that’s essentially what we’ve had.”

Climate justice activists like UPROSE’s Executive Director Elizabeth Yeampierre also criticize the mayor’s approach, giving him only a passing grade.

“I would give him a C. I think that he had an opportunity to take the momentum that existed under the Bloomberg administration and amp that up, and what we saw was a level of passivity that was inconsistent to what we were learning about climate change.”

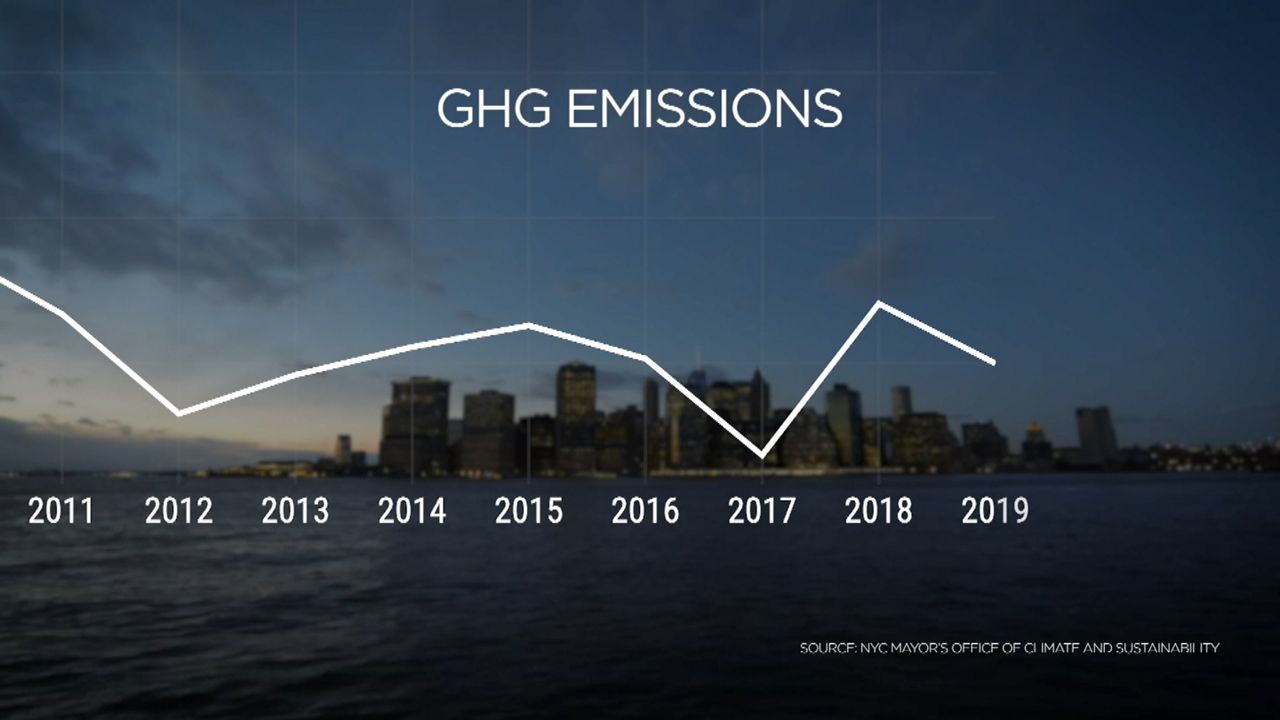

And it’s not only when it comes to climate adaptation. Despite de Blasio’s pledges, the latest data available show greenhouse emissions are up from 2017 levels.

“I think that Mayor de Blasio needed to really prioritize fighting climate change and really making sure that we were taking actions and not just talking about it when it was convenient,” Julie Tighe, president of the New York League of Conservation Voters, said.

The recent closure of the Indian Point nuclear plant in Westchester County might also increase emissions further in the short term, making the city more reliant on natural gas to close the gap.

“New York City has often been a leader on the environment and on climate change,” Tighe said. “We need to be front and center. Whatever happens at the national level, we need New York City to be advancing change and being real leaders on this, and I don’t think we’ve had enough of that over the last eight years.”

FROM DE BLASIO TO ADAMS: WHAT DOES THE NEXT ADMINISTRATION HAVE TO BUILD ON?

Critics do acknowledge the future positive impact of Local Law 97.

Signed by de Blasio in 2019, it will mandate retrofitting of big buildings in order to reduce greenhouse emissions by 40% by 2030 and by 80% by 2050.

This would be de Blasio’s top climate legacy item, according to Zarrilli.

“The second is going to be our work to divest from our pension funds, remove billions of dollars from the fossil fuel industry and redirect those funds into billions of dollars of new clean energy investment,” Zarrilli added.

That move was finally announced early this year.

It’s estimated to amount to $4 billion.

After years of talking about it, it’s now that New York and other cities are finally taking some action and slowly divesting their pension funds from fossil fuel companies.

In its goal to reduce emissions, New York also needs cooperation from key players like Con Edison, which deliver power to millions of New Yorkers. Its president, Tim Cawley, recently announced an ambitious timeline that includes delivering 100% clean power to its customers by 2040.

Cawley defends de Blasio’s record on mitigation.

“He has put a focus on it. I would say he’s one link in a series that would get us there, but I think his focus has helped push the ball forward for New York City and around the area,” he said.

It’s not only New York that’s having a hard time reducing emissions and transitioning to clean energy sources. The international community is generally walking away from its polluting ways very slowly. And when it comes to adaptation, complex infrastructure projects always take a long time to fund, design, negotiate and get built.

“Does more work need to happen? Absolutely,” Bavishi acknowledged. “I’ve always said resiliency is a process, not an outcome, and we will continue to do this work and build on the investments we’ve made, but there’s an enormous amount of work that’s underway and plenty to build on for the next administration.”

_CGPKG_Qns_Kissena_Park_Flooding_Town_Hall_CG)