When Eric Adams first released a climate plan, it occupied just the final three headings of his “100 Steps Forward For NYC”: expanding composting, educating high school students for jobs in the green economy and converting the bus fleet to electric.

His campaign later released an expanded environmental plan, on Earth Day, but it lacked the specificity of his primary opponents’ visions, calling for the city to “move boldly forward on resiliency projects” without citing any examples.

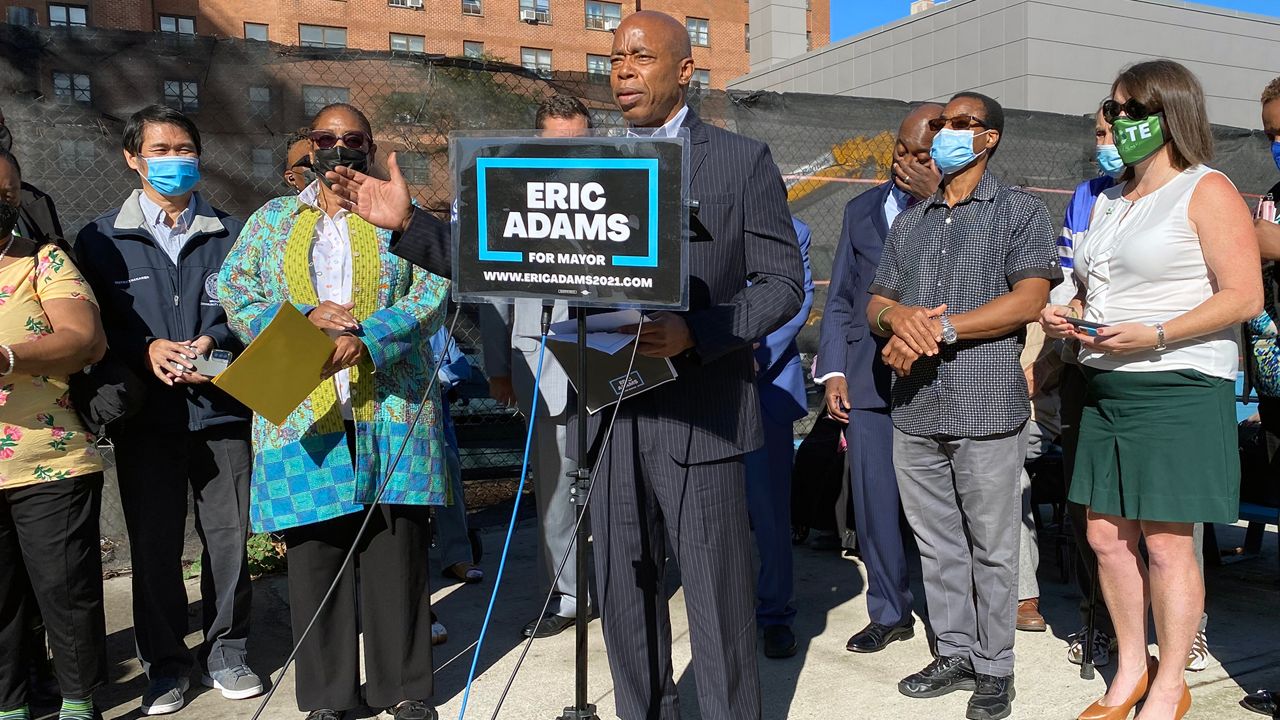

Now Adams, the Democratic mayoral nominee who is widely favored to win November’s general election, has released a new plan in the wake of Hurricane Ida, outlining a range of policies for adapting the city to extreme weather.

Experts on climate resiliency say that the plan represents a welcome departure from the first two documents, filling in key details — tax credits, borrowing programs, specific neighborhood plans — on how and where an Adams administration would implement its climate goals.

And unlike Adams’ earlier efforts, or the longtime approach of Mayor Bill de Blasio, the plan shifts the spotlight from sunnier goals, like recycling, urban agriculture and “green art,” to the sober work of preparing the city’s citizens and infrastructure for inevitable impacts that are baked into our altered climate.

That realism is vital, experts say, because Adams cannot sidestep climate change.

“He’s gonna be the mayor that has to solve this problem for the city. We can’t wait another four or eight years,” said Amy Chester, the managing director of Rebuild By Design, a resiliency consulting firm, who served as an adviser to former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and who provided input to Adams on his plan. “This will end up being a defining issue in his administration.”

In an emailed statement, Evan Thies, a spokesperson for Adams said that Adams has a long track record of talking about the city’s environment and combating climate change.

“Eric sees resiliency as a public safety issue — and his resiliency plan released last week explains in detail many of the investments he called for during the primary through his green jobs capital program,” Thies said.

‘I have never witnessed something like this’

Adams’ plan comes amid renewed scrutiny of the city’s climate preparedness after a summer of flooding, intense heat and the worst air quality in 15 years caused by wildfire smoke drifting from the other side of the continent.

Flooding caused by the remnants of Hurricane Ida on the first night of September showed just how high the stakes would be to continue the current pace of adaptation, when 13 people died locally, including 11 in overrun basement apartments.

Adams, a life-long city resident, said during the storm that he was floored by its impact in inland neighborhoods.

“We have to deal with intervention and prevention,” Adams said Friday in announcing the plan. “We can’t play scatter and pray when each storm comes.”

Adams’ new plan, released on the last day of Climate Week NYC — a series of events on climate change — shows a clear step away from his earlier focus on long-term sustainability efforts.

De Blasio has also often prioritized resiliency initiatives below efforts to add new sources of renewable energy and reduce the city’s energy usage, saying that “the very best thing we can be doing is going for the root cause, and reducing our reliance on fossil fuels, rapidly, quickly.”

Adams’ plan draws a sharp distinction with that approach.

“As the flooding from Hurricane Ida underlined with devastating effect, our focus can no longer solely be on climate change prevention,” the plan reads. “It must also be on the interventions we need right now to warn, educate and insulate New Yorkers from damage and death.”

Resiliency experts who have for years been frustrated by de Blasio’s preference for energy projects said they welcomed Adams’ reframing.

“We believe those efforts need to be equal in every way, so we were pleased to see that,” said Cortney Worrall, the CEO of the Waterfront Alliance, a climate change preparedness advocacy group. Worrall said she spoke with Adams directly about his plan.

The plan is divided into near-, medium- and long-term goals, with the first section sharing some similar goals with de Blasio’s recently released task force report on updating the city’s extreme weather response.

Both plans call for immediate changes to the city’s weather alerting system, and include measures to begin bringing illegal basement apartments into compliance with city building codes.

But Adams’ plan does not embrace de Blasio’s “aggressive” alerting approach when any risk of flash flooding is predicted, and instead suggests a simplified three-level scale of emergency, as well as “geo-targeted, hyper local” alerting. De Blasio’s approach, experts say, risks alert fatigue.

“We don't want to be in a situation where the city has cried wolf time and time again, and then people don't take it seriously when it’s a really bad storm,” Chester said.

Adams’ plan also does not mirror de Blasio’s new effort to create a “census” of illegal basement apartments and “identify all basement dwellers citywide.” City crackdowns on illegal basement units have already rattled residents, many of whom are undocumented and fear being unhoused or deported.

In an emailed statement, Laura Feyer, a spokesperson for the mayor, said that the city is not evicting people from illegal basement apartments, but that the city’s buildings department can issue vacate orders if the unit’s condition is “life threateningly dangerous.”

Worrall said that Adams’ plan further balances housing and safety needs by calling for building new affordable housing outside of areas at risk of flooding and other strong climate effects. The plan also includes some ideas for funding resiliency projects.

“There needs to be a comprehensive approach to protecting people in their homes and at the same time recognizing the need for building more affordable housing,” she said.

Adams’ plan also includes calls for a voluntary, city-funded buyout program for people who live in areas that face high risks of flooding -- an issue that politicians often consider something of a third rail. Already, some homeowners in Queens have called on the city to buy their homes and allow them to move.

“We need that, and we need an ongoing funding source for it,” said Kate Boicourt, the director of New York and New Jersey coasts at EDF Action, the advocacy arm of the Environmental Defense Fund.

Boicourt said that she appreciated that Adams’ plan includes roles for private businesses and developers, something which de Blasio’s post-Ida report alludes to but which his administration has largely avoided in approaching resiliency initiatives.

‘More details needed’

Adams’ plan also picks up where the de Blasio administration left off, saying he will “fast-track” several as-yet-unfunded resiliency programs created in the last eight years, such as for East Harlem, Hunts Point and Lower Manhattan, and that he will create “a single comprehensive city-wide resiliency plan” with neighborhood specific assessments.

What’s missing, experts say, is further specifics on how Adams will prioritize the many elements of the plan and how he will fund them.

“There are more details needed to make sure that we’re thinking about this comprehensively in every agency,” Boicourt said. “That’s something for the first 100 days, releasing a plan for how this will get done.”

The city’s hopes for an immediate influx of federal relief funding, included in a temporary funding resolution to stave off a government shutdown, were dashed Monday evening when Republicans in the Senate blocked the resolution.

Adams’ priorities will be tested in his first executive budget, said Sandy Nurse, a candidate for City Council who is expected to represent District 37, which includes Bushwick and Ocean Hill in Brooklyn.

“It’s not just about new plans. There's a lot of good stuff that exists already,” Nurse said. “If the things that have passed are not funded in the upcoming budget, it will be a huge failure for all of us.”