NEW YORK CITY — Pria Sibal listened over the telephone as her client — an out-of-work mother of three who years ago escaped an abusive partner — wept tears of rage at what her husband had done.

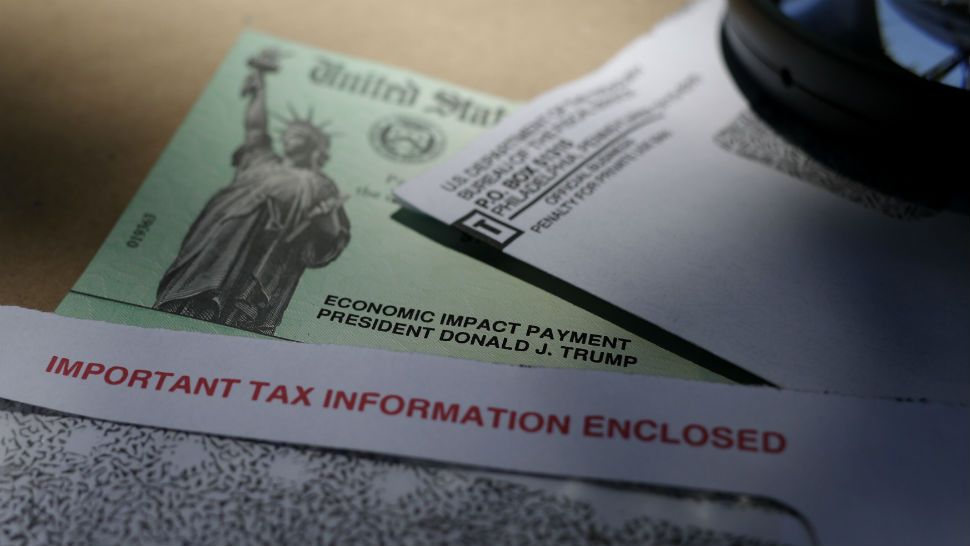

He’d taken her stimulus check.

“She told me she went and was shouting outside his house,” Sibal said. “Wait until this is over,” the woman told him. “I’m going to get every penny back and more.”

What You Need To Know

- Domestic abuse service providers across New York City are receiving reports of spouses wrongfully withholding stimulus checks

- This new expression of financial abuse, which affects 99 percent of abuse survivors nationwide, limits survivors' ability to escape dangerous situations or support their families amid an economic crisis

- Advocates say recourse is hard to secure for victims of economic oppression, a newly recognized form of abuse not yet included in New York City Human Rights Law

- Resources for New York City abuse survivors are listed below

Sibal’s client is among a rising number of New York City women facing a new form of domestic abuse during the novel coronavirus pandemic and economic crisis spurred by New York’s stay-at-home order.

Sibal, an economic advocate with the domestic violence organization Sakhi, said almost a dozen clients have reported abusive partners directing the $2,400 check into accounts their spouses cannot access, then refusing to split the cash.

Similar reports have reached New York City and State domestic violence support offices, Sanctuary for Families and the Urban Resource Institute, both among the nation’s largest providers of domestic violence services.

“The stimulus check is a huge way in which financial abuse has been occurring,” Teal Inzunza, URI Economic Empowerment Program Director, said.

“I don’t think we should be surprised,” added Kelli Owens, executive director of the New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence.

“But should we be alarmed? Absolutely.”

Sanctuary For Families is pursuing about three or four cases — urging survivors to report their claims to the government agencies issuing the checks — and expects to see more in the weeks ahead, Legal Center Director Dorchen Leidholdt said.

While evidence remains anecdotal, numerous agencies across the city have received similar reports, spurring Sanctuary for Families to launch an investigation among its clients, according to Leidholdt.

“It’s crucially important when a survivor hasn’t yet been able to secure public assistance,” Leidholdt said. “You could pay the rent, you could buy groceries.”

City records show survivors are seeking help in record-breaking numbers.

The city’s domestic abuse services website NYC HOPE — where survivors can find access to public benefits, housing referrals, and legal services — has seen an average of 798 visits per day with nearly 99,000 visits between March 18 and July 21, officials said.

Before the pandemic, the average count was 45.

The stimulus check theft is a symptom of what Inzunza described as a “perfect storm” of abuse spurred by the COVID-19 crisis, which threatened families’ livelihoods as well as their lives.

For Sibal, this means helping her clients has become a grueling seven-day-a-week job, and her clients’ stories have become her own.

Sibal encouraged her client to take action against the husband who claimed her stimulus cash as his own. She helped secure orders of protection for two pregnant women whose partners punched them in the stomach in attempts to abort baby girls the men did not want.

She spent one Friday night scrambling to find shelter for a woman hospitalized with Multiple Sclerosis complications who didn’t want to return to her physically abusive husband.

“She said, ‘I just don’t want to go home,’” Sibal said. Hours later, once Sibal had succeeded in securing her client shelter, her own husband returned home.

“He said, ‘Let’s open a bottle of wine,’ and I just started crying.”

What keeps so many of these women trapped in these homes is financial anxiety only worsened by COVID-19, which moved an already complex legal system online and sparked fears of public places, such as shelters, Sibal explains.

“There are so many who don’t have the courage to do that,” Sibal said. “They’re kind of resigned.”

The stimulus check problem is especially sticky because of the inclusion of the Internal Revenue Service, authorized to manage federal stimulus checks through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act in March.

The documents required to claim the cash — such as social security cards and government-issued ID cards — are things abusers will destroy to maintain power and control, Inzunza explained.

“The IRS wanted to get this money very quickly, so that was not set up in a way that worked very well,” Inzunza said. “It would be easier if the IRS and the folks creating these packages thought about survivors.”

While the IRS does have a process for reporting stolen checks, the agency warns it could takes six weeks or longer for a response, and legal experts say it remains unclear whether a spouse claiming the entire amount constitutes theft.

Bankruptcy attorney David Waltzer, who says he’s also received reports of spouses seizing stimulus checks, argues that the cash should be split as is financial liability.

“A refund belongs 50-50 to the spouses,” Waltzer said. “If you’re looking for rights, it goes into the realm of marital distribution because this is a marital asset.”

The equal divide should apply even when one spouse earns more than the other because of what he calls “sweat equity,” or the unpaid work one partner does that allows the other to earn an income.

But Waltzer notes the stimulus is a unique asset and may require a unique law that does not yet exist.

“It’s an usual thing, it’s not exactly a tax refund,” Waltzer said. “I don’t know of a law where it’s been tested, but I don’t know because it’s so new.”

Novelty also becomes a problem with the relatively recent concept of financial abuse — a tactic to exert control over a partner by claiming control of family funds — which the National Network to End Domestic Violence reports 99 percent of all domestic violence survivors experience.

Financial abuse takes on many forms, from racking up debt on family credit cards or forcing a partner to hand over a paycheck, explains Maureen Curtis of the victim services nonprofit Safe Horizon.

“You don’t have freedom in what your choice is in that relationship,” Curtis said. “That adds up to real trauma.”

But while financial abuse is prevalent, little regulation exists, which makes recourse hard to come by.

Economic oppression is not recognized under New York City’s Human Rights Law — and although Council Member Justin Brannan introduced legislation in November 2019 to include it as a form of abuse — the bill faces an uncertain future as City Council grapples with the pandemic.

And coerced debt — debt racked up by an abuser under the name of a partner who gave permission under the threat of violence — is not recognized in New York as a form of identity theft.

Curtis compares such economic oppresion to marital rape, a form of abuse only outlawed in New York in 1984.

Before then, “They wouldn’t consider the types of coerrive control that were used to force that person to have sex,” Curtis said. “We see the same thing with financial abuse.”

The severity of the issue in June spurred Melissa DeRosa, top aide to Gov. Andrew Cuomo, to call on the state’s domestic abuse office to form a pilot project to help survivors restore their credit scores, which Owens said will likely include flexible funding.

“We knew we needed to look at a new delivery model that wasn’t just access to shelter,” Owens said. “How do we get financial stability to those seeking freedom?”

In New York City, the Mayor's Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence launched this summer a microgrant program for survivors that has provided 62 people with an average amount of $1,054, officials said.

Its Family Justice Center Operations and Programming also connects survivors to W!se financial literacy courses, where they can learn basic banking skills to achieve greater economic independence, Assistant Commissioner Jennifer DeCarli said.

“So much about domestic abuse is about taking control away from somebody,” De Carli said. “That’s why I get so jazzed about financial literacy classes — knowledge is power.”

But time may be running out as an increasing number of women — often burdened by rents in arrears, jobs lost, and children to feed — look this summer to leave their partners.

Safe Horizon — which manages the city’s domestic abuse hotline — saw in June a 50 percent increase in shelter requests as compared to June 2019, the organization said.

Several providers said they suspect the trend, once again, is spurred by the pandemic.

“In the summer we’ve always seen an uptick,” DeCarli said. “Before, it was getting ready for school to start. Now it’s people preparing for a possible second wave.”

Resources (Those in immediate danger should call 911)

National Domestic Violence Hotline

- Helpline: 1 (800) 799-7233

- Text “LOVEIS” to 1 (866) 331-9474

NYC Domestic Violence Hotline/Safe Horizon

- Helpline: 1 (800) 621-4673

- Brooklyn: (718) 250-5113

- Bronx: (718) 508-1220

- Manhattan: 1-212-602-2800

- Queens: (718) 575-4545

- Staten Island: (718) 697-4300

NYC Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project

- Helpline: (212) 714-1141

NYC Resources For Survivors During COVID-19

New York State Office For The Prevention of Domestic Violence

- Helpline: (800) 942-6906

- Text (844) 997-2121

- Helpline: (212) 868-6741

- Text: (305) 697-2544

- Email: advocate@sakhi.org

- Legal helpline: (212) 349-6009 x 246