Elementary-aged children are much closer to gaining access to a COVID-19 vaccine.

On Tuesday, an advisory panel to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) voted in favor of recommending emergency use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in children five to 11 years old.

The meeting delved into data from Pfizer’s vaccine trial in children, which found the lower dose regimen — a third of the dose given to adults — is 90.7% effective in preventing symptomatic illness.

The dosage for younger children is also a slightly different formula, which allows storage in a refrigerator freezer at around 2 degrees Celsius. The original formula requires special freezers reaching sub-80 degree temperatures.

Members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee pointed to the need to offer greater protection to children so they may return to some level of normalcy.

“I will say that the school closures and disruptions I think have been enormous, and I think that we need to weigh that against the benefits that we would see from the vaccine. And I definitely think the benefits outweigh that. But obviously we’ll have to follow these kids for some time to see what happens,” said temporary voting member Dr. Jeannette Lee, a professor of biostatistics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Several members, though, argued the risk-benefit analysis was not as clear with the younger age group, where severe COVID illness and death is considered rare.

A presentation from CDC experts showed the burden of disease among children is not inconsequential. According to the latest data, experts say children have a similar risk of infection to adults, particularly with the delta variant dominating.

Committee member Dr. Michael Kurilla, an infectious disease pathologist at the NIH, was the one member to abstain from voting. He criticized the question posed to the panel, saying it failed to offer providers and parents necessary flexibility to make the best and safest decision for children.

“Particularly with the percentage of the population that has already been infected previously with COVID — and I think 40% is probably a lower limit — I think that the possibility that they likely only need one dose at best, is probably going to be more than sufficient for them. So I think the idea of doing it under an EUA, two doses for everybody without any flexibility around this, I think is going to not go over very well,” said Kurilla.

Many of the participants in Pfizer’s pediatric vaccine trial are children of healthcare workers, another, little known contribution of first responders, after nearly two-years of relentless pandemic response.

Emergency room nurse Isabel Perales and her husband Jesus Perales, believe they made the right decision, enrolling their two children Zoe and Maximillian into Pfizer’s pediatric vaccine trial.

“We just wanted our kids to be safe. I think that's the biggest thing - this is scary enough. And to think that something could happen to your kids, you want to do everything you can to kind of keep them safe within what's possible to you,” said Mr. Perales.

Jesus Perales would bring food to their master bedroom where Isabel quarantined away from the family.

“I would isolate, so I’d go days without seeing them or being around,” said Isabel Perales. “That was tough on them and me.”

Life became less stressful once both parents were able to get vaccinated. Zoe and Max say they are proud of their mom and also wanted to do their part.

"I feel like I'm helping other kids and grown-ups, to show them how the vaccine works and how it's not scary for younger kids,” said Max, who is now eight. “I feel good about myself because I'm helping thousands of people.”

Dr. Yvonne Maldonado is the lead investigator of their trial site at Stanford Medicine, and says working with the families on a solution to protect children was inspirational.

“We are extremely blessed in this country to have the resources that we do to even be thinking about giving kids vaccines right now when we know that in many parts of the world, people don't have access,” says Maldonado. “I'm really grateful for the families and the children who have come forward to participate in these trials. They do take a risk. Obviously, we think it's a very low risk, but they were brave and they have been incredible partners.”

According to data presented during the FDA advisory panel meeting, the risks for children five to 11 are similar to those seen in older adults. The younger kids had less severe reactions like fever, chills, and fewer reports of fatigue, headache compared to teens and adults. And unlike those 55 and older, children in the trial were less likely to experience joint pain.

“The shot felt like the flu shot,” says Max. “Maybe a day and a half after the shot, I felt soreness in my arm, but that's pretty much it.”

His sister Zoe, who is six, agreed.

Committee members expressed a lot of concern surrounding the risk of myocarditis a rare form of heart inflammation seen mainly in teenage boys and young men. Pfizer’s trial for five to 11 year olds did not detect any cases, but was also not large enough to capture rare adverse events like myocarditis. The highest percentage of cases have been found in 16 and 17 year old males.

Data from vaccinated teens 12 to 15 shows lower rates of myocarditis than what has been seen among 16 to 29 year olds. Cases that were only detached experts say, because of the large number of teens getting vaccinated.

“We’re never going to learn about how safe the vaccine is unless we start giving it. That’s just the way it goes, it’s how we found out about rare complications of other vaccines like the rotavirus vaccine,” said temporary voting member Dr. Eric Rubin, who serves as editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Maldonado says Pfizer’s trial is close to the typical size of pediatric vaccine trials, including data from more than 3,000 participants five to 11 years old.

“We've already given vaccines to almost half of all children, 12 to 15 years of age. Other countries have vaccinated young adults as well. So we have a very good handle, more than any other vaccine, around what the safety is from millions and millions of doses administered,” says Maldonado.

Dr. Maya Ramagopal is an investigator of Pfizer’s trial site at Rutgers University, she says they saw no cases of the rare inflammation disorder among participants there. Though the pediatric pulmonologist says they are seeing more unvaccinated children come into the hospital with what is now being called Post Acute Symptoms of COVID (PASC), otherwise known as long COVID.

“These children would have had a COVID infection, it could be severe or not so severe, but weeks later, they continue to have difficulty breathing. They have fatigue,” says Ramagopal. "We've had cases of high school athletes, for example, who are unable to compete or perfrm at the level that they were prior to COVID."

The long term impacts of COVID were also discussed during the FDA’s advisory committee meeting. FDA researchers say they are just now starting to understand the lingering effects of COVID-19 in children. Preliminary research into Pfizer’s pediatric trial shows no signs of long COVID among the handful of so-called breakthrough cases. But FDA officials say the research will continue, with five post-authorization safety studies with children planned, including a 5-year study aimed at measuring the true risk of myocarditis.

It is expected the FDA will formally adopt the committee’s recommendation. The CDC’s vaccine advisory committee will also consider use of the Pfizer Vaccine in children five to 11 years old. If CDC Director Rochelle Walensky gives it the green light, the vaccine could be available for use in early November.

The question on the minds of most is – is this it? During a White House COVID Response Team Briefing last week, where officials unveiled their vaccine distribution plan for children, Dr. Anthony Fauci said vaccinating younger, school-aged kids against COVID is a crucial step to ending the pandemic and reaching herd immunity.

“If we can get the overwhelming majority of those 28 million children vaccinated, I think that would play a major role in diminishing the spread of infection in the community,” said Fauci.

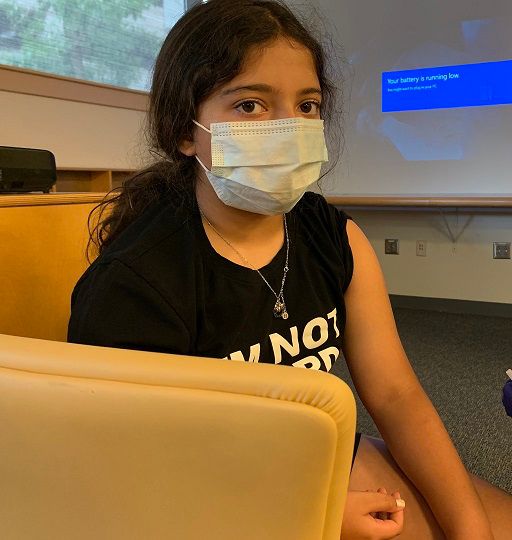

Dr. Ramagopal says many of the children in her arm of the vaccine trial were the ones pushing their parents to allow them to participate, with that very hope- getting back to "normal" life. Dr. Nisha Gandhi allowed her 10-year-old daughter Maya Huber to participate in Rutgers’ trial.

“She wants life to get back to normal. She wants to be able to see her friends again indoors, especially now that with the fall and winter coming again. The summer was nice and easy, camp was easy because there's a lot of outdoor activities. It's easy to hang out outside, play with your friends, but once they go inside, they have to mask up and it just takes a toll,” said Gandhi.

Dr. Ramagopal says even after vaccines are approved for children it may be a while before kids can say goodbye to masks.

“I don't know whether you're going to get one hundred percent of the kids vaccinated to be able to say, well, nobody needs to mask. And you also have to look at the community spread at that point, right? So that may be a ways away, but I think we can start with getting everybody vaccinated. As many as possible,” says Ramagopal.

That is the plan. White House officials say the U.S. has purchased enough Pfizer vaccine to inoculate all 28 million 5 to 11 year olds, with 15 million doses ready to be shipped out once the FDA and CDC give it the green light.

At least to start, Dr. Maldonado thinks the vaccine will offer peace of mind to many children and their families.

“What the vaccines will do for children is allow them to go back to sports, to social activities, to sleepovers, all of those things, in a vaccinated pod or in a vaccinated community,” Maldonado says. “And if children do happen to be exposed, their likelihood of becoming infected will be extremely low and will be highly unlikely to lead to any severe outcomes. So that's a really big difference from where we were last year.”

According to a poll done by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor, just over a third of parents surveyed in mid-September say they would vaccinate their children against coronavirus. Another third — about 32% — say they will wait and see before deciding whether to vaccinate their children, with about a quarter of parents polled saying they would not allow their children to get inoculated against coronavirus.

But while White House officials proclaimed the availability of vaccines for kids would help to end the pandemic, Coronavirus Response Coordinator Jeffrey Zients stopped short of committing to a vaccine mandate for children. He said those decisions should be made locally.

“School vaccination requirements have been around for decades. And those decisions should be made at the state and local level,” said Zients. “We support states and school districts taking actions to ensure that everyone who’s eligible gets vaccinated.”

Some states have already announced there will be a vaccine mandate for all school-aged children, including California. Officials in New York are also discussing the move. For now though, doctors on the frontlines say what is needed most is better education about the safety and necessity for vaccines.

“I think education is key and I think the more people that get the vaccine, the more it spreads in the community,” said Ramagopal. “We always tell parents that, ‘remember, you're not just doing this for yourself, it's also for the kids and other patients, adults even, who for some reason or other, they cannot get the vaccine.’ And if we're aiming for herd immunity, like we are, everyone has to do their part.”