CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — For longtime UNC alumni, the fight for freedom of speech on campus has been decades in the making. In 1963, students and staff at Chapel Hill were fighting for their First Amendment rights against the newly imposed Speaker Ban Law.

The law prohibited certain controversial groups from speaking on campus.

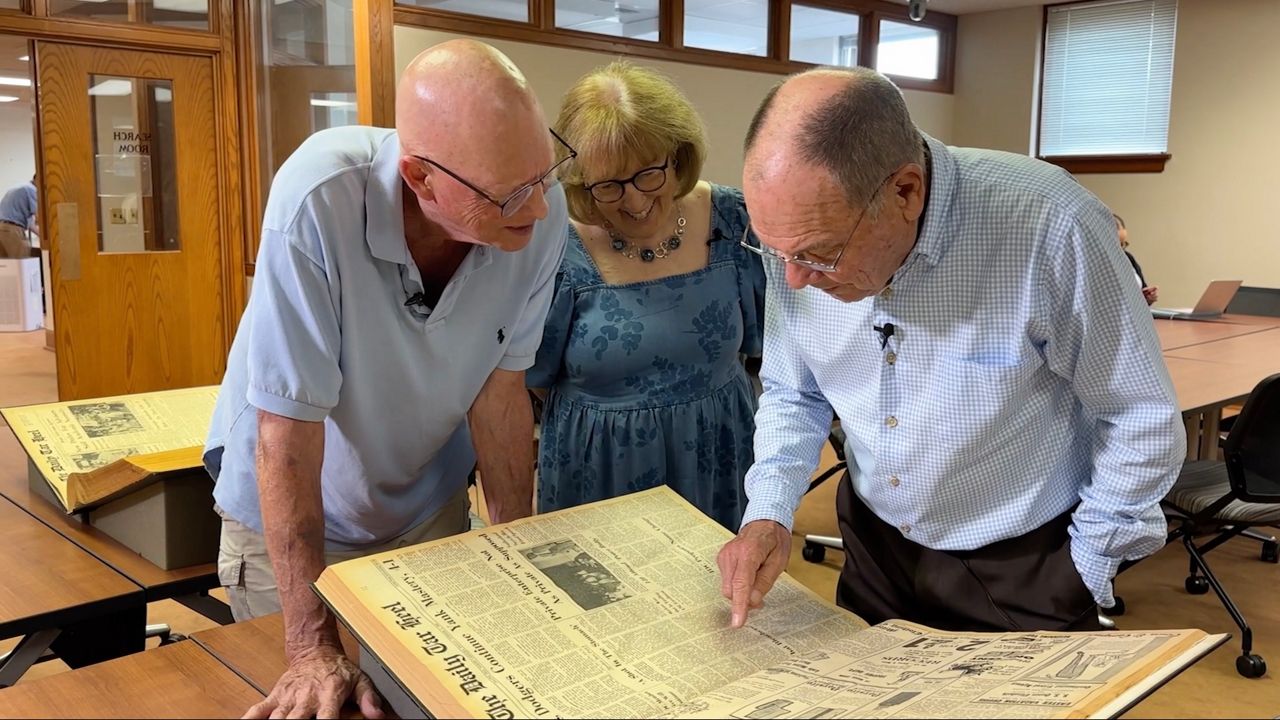

Hugh Stevens, Jock Lauterer and Lynne Lauterer were all students at UNC during the Speaker Ban. They reflected on what it was like fighting for First Amendment rights 60 years ago.

“I think we understood pretty quickly that it was a big deal,” Stevens said.

“Every day there were protests about a lot of things going on in addition to this,” Jock Lauterer said. “But this was the one that galvanized the student body.”

For Stevens, it was all about protecting First Amendment rights.

“Some of Jesse Helms viewers probably thought, hey he’s doing a great job trying to keep those communists off the campus,” Stevens said. “But the academic world, the university community, recognized it immediately as a free speech issue.”

It started back in the summer of 1963, when the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Speaker Ban Law. The law prohibited people from speaking on state university campuses who were known communists, or advocating to overthrow the Constitution in any way. The ban sparked a major controversy on campus and inspired years of activism to overturn it.

“There was a lot of speech I heard in the seven years I was at Chapel Hill that was offensive,” Stevens said. “But that’s what the First Amendment is all about.”

As editor of the Daily Tar Heel student newspaper, Stevens helped put the Speaker Ban all over the front page. Jock Lauterer was a photographer for the paper back then.

“I was not so much on the intellectual side as I was on the visual narrative that was unfolding in front of us,” Jock Lauterer said. “When I took it, I did not understand the significance of what I was doing, obviously. But I realized, number one, that I had this great view of this demonstration, and then I had this overarching sort of aura type feeling of ‘this is important.’”

At the protest, students invited two communist speakers to campus. Although many university officials, including President Bill Friday, were fighting against the Speaker Ban, they had to enforce the law. This was the catalyst that allowed a lawsuit to be filed, saying the Speaker Ban was unconstitutional.

Stevens said since the communists couldn’t speak on campus, they stood on the sidewalk off campus and spoke to the students on the other side of the wall.

“One of the attitudes a lot of students had was [a] sort of resentment of the idea that we somehow were vulnerable to whatever ideas they were,” Stevens said. “We weren’t all going to go off and join the Red Army.”

In early 1968, the Speaker Ban was declared invalid and unconstitutionally vague by a panel of three federal judges. It was a huge win for free speech and for the group of students who had lived through it.

“I thought of it as being how important it is to stand up for what you believe in and that it can make a difference,” Lynne Lauterer said. “Because it did make a difference in the Speaker Ban Law.”

Although they eventually won that fight, the issue of free speech never truly went away. Other groups of students and faculty have continued to fight for their rights over the years.

“My view is if you don’t agree with the speaker or you don’t think a speaker ought to be listened to, don’t listen to him,” Stevens said. “Don’t go hear him. Don’t give him your presence. But if you do, be respectful. Let them talk. And then if you have something to say about it afterward to criticize, fine.”

Stevens and the Lauterers say they don’t want to see history repeat itself. Instead, they encourage people to continue to stand up for their first amendment rights.

When the Speaker Ban case was over, the Lauterers had graduated from UNC and eventually became professors. They met each other over 25 years later despite being at the same protest all those years ago. They eventually got married.

Stevens was in law school at UNC when the case ended. He became a First Amendment lawyer, vowing to uphold the Constitution whenever possible and arguing in many cases supporting free speech and open governance.